The automotive world is experiencing a seismic shift as electric vehicles rapidly replace their internal combustion engine predecessors.

While EVs offer undeniable benefits instant torque, zero emissions, lower operating costs, and cutting-edge technology, they’ve also left behind a treasure trove of mechanical marvels that defined the golden age of motoring.

These old-school technologies weren’t just functional components; they were tactile, visceral experiences that connected drivers to their machines in ways that modern electric powertrains simply cannot reproduce.

For enthusiasts who grew up turning wrenches in their garages, the loss of these technologies represents more than just mechanical obsolescence it’s the end of an era.

The symphony of a naturally aspirated V8 at full throttle, the satisfying engagement of a manual transmission, the raw mechanical feedback through an unassisted steering wheel these are sensations that electric motors and computer-controlled systems can simulate but never truly replicate.

They represent a tangible, analog relationship between human and machine that’s being systematically eliminated in the pursuit of efficiency and automation.

This isn’t an argument against progress or electric vehicles themselves. Rather, it’s a nostalgic appreciation for the mechanical artistry and driver engagement that defined automotive culture for over a century.

As we embrace the electric future, it’s worth remembering what we’re leaving behind ten technologies that made driving not just transportation, but an experience worth savoring.

1. The Internal Combustion Engine’s Soundtrack

The auditory experience of a traditional internal combustion engine represents perhaps the most emotionally resonant loss in the transition to electric vehicles. For over a century, the engine’s sound has been the automotive equivalent of a musical instrument, with each configuration producing its own distinctive voice.

A Ferrari V12 screams with operatic intensity, its 12 cylinders firing in perfect harmony to create a spine-tingling crescendo that climbs toward an 8,000+ RPM redline.

A Detroit V8 rumbles with a deep, chest-thumping bass note that announces its presence from blocks away. An inline-six produces a silky-smooth howl, while a boxer engine creates its characteristic offbeat burble that’s instantly recognizable.

These sounds aren’t merely noise they’re the result of complex mechanical orchestration. Exhaust pulses, intake resonance, valve train clatter, turbocharger whistles, and supercharger whines combine to create an acoustic signature as unique as a fingerprint.

Enthusiasts can identify specific engines blindfolded, distinguishing a Subaru’s flat-four from a Porsche’s flat-six, or a Honda VTEC from a BMW inline-six.

The engine’s soundtrack also serves as crucial feedback for skilled drivers. The changing pitch and intensity communicate information about engine speed, load, and mechanical condition.

Performance drivers use this auditory data to execute perfect rev-matched downshifts, time gear changes without looking at the tachometer, and detect mechanical issues before they become failures.

Electric motors, by contrast, produce little more than a subtle whir a nearly silent propulsion that, while efficient and futuristic, lacks the emotional resonance of internal combustion.

The loss of engine sound fundamentally changes the driving experience from a multi-sensory event to something more sterile and disconnected, no matter how impressive the performance figures might be.

2. Manual Transmission Mastery

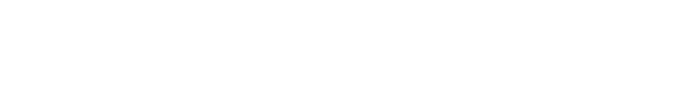

The manual transmission represents one of the most engaging forms of human-machine interaction ever devised for automobiles. Operating a traditional three-pedal setup requires coordination, timing, and skill transforming the simple act of acceleration into an interactive dance between driver and machine.

The manual transmission makes the driver an active participant in the power delivery process rather than a passive operator, creating a sense of mechanical connection that automatic and single-speed EV drivetrains cannot replicate.

Learning to drive a manual transmission is a rite of passage that develops genuine automotive skill. Mastering the clutch engagement point, understanding gear ratios, executing smooth shifts, and performing advanced techniques like heel-toe downshifting or rev-matching represents a learning curve that rewards practice and dedication.

A poorly executed shift results in jerky motion or grinding gears immediate, unmistakable feedback that encourages improvement. Performance driving enthusiasts particularly cherish manual transmissions for the control they provide.

A skilled driver can hold gears longer for optimal acceleration, select the perfect gear for corner exit, or brake the engine precisely while downshifting.

The manual transmission allows drivers to keep the engine in its powerband, maximizing performance in ways that even the most sophisticated automatic or DCT cannot always predict.

The mechanical act of shifting feeling the linkage engage each gate, sensing the synchros align, timing the clutch release with throttle application creates tactile satisfaction that’s absent in EVs.

Beyond performance, manual transmissions offer a deeper understanding of how cars work. Drivers learn about torque, gear ratios, mechanical advantage, and powertrain dynamics through direct interaction. This educational aspect has fostered generations of enthusiasts who understand their vehicles at a fundamental level.

Electric vehicles, with their single-speed reduction gearboxes, eliminate this entire dimension of driving. The instant torque delivery requires no gear selection, no clutch modulation, no rev-matching.

While this makes EVs easier to drive and often quicker in straight-line acceleration, it removes layers of engagement that made driving rewarding beyond mere transportation.

Some manufacturers have experimented with simulated gear changes in EVs Hyundai’s Ioniq 5 N offers a “virtual” manual mode with fake gear shifts but these electronic imitations lack the genuine mechanical consequences and authentic feedback that make real manual transmissions so satisfying.

3. Carburetors and Mechanical Fuel Delivery

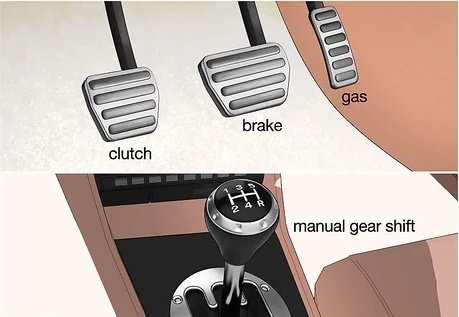

Before electronic fuel injection became universal in the 1980s and 90s, carburetors represented the pinnacle of mechanical ingenuity purely mechanical devices that mixed air and fuel in precise ratios using nothing but airflow physics, float chambers, jets, and vacuum signals.

These intricate assemblies of brass passages, needle valves, accelerator pumps, and choke mechanisms required intimate understanding and hands-on tuning, making them both beloved and occasionally frustrating pieces of automotive technology.

Carburetors gave shade-tree mechanics genuine control over their engines’ fuel delivery. By changing jet sizes, adjusting float heights, or modifying venturi dimensions, enthusiasts could tune their engines for specific purposes more power, better economy, or optimal performance at different altitudes.

This tunability made carburetors endlessly customizable but also temperamental. They required seasonal adjustments, altitude compensation, and occasional rebuilding. Cold starts often needed manual choke operation, and hot restarts could prove challenging as heat-soaked fuel vaporized in the carburetor bowls.

Multiple-carburetor setups like the iconic six-pack (three two-barrel carbs) on muscle cars or the quad carburetors on Italian exotics took this complexity to artistic levels.

Synchronizing multiple carburetors required skill, patience, and a good ear, as each unit needed to contribute equally to engine performance.

The mechanical linkages connecting multiple carburetors, the progressive opening of secondary barrels, and the vacuum-operated secondaries in performance applications all represented visible, understandable mechanical solutions to fuel delivery challenges.

The sensory experience of carbureted engines differs distinctly from fuel injection. The sound of air rushing through carburetor throats, the occasional backfire through the carburetor when tuned aggressively, and even the distinctive smell of a rich mixture all contributed to the experience.

Modern fuel injection and particularly EV powertrains that require no fuel delivery system whatsoever offers superior performance, reliability, efficiency, and emissions control.

Electronic fuel injection adjusts instantly to changing conditions, requires no user intervention, and delivers precisely metered fuel under computer control. Yet this computerized precision eliminates the mechanical artistry and hands-on involvement that carburetors demanded.

The knowledge required to properly jet a carburetor, understand venturi principles, or diagnose a flooding condition represented genuine mechanical expertise that’s now obsolete, replaced by oxygen sensors and engine control modules that most owners never think about and cannot adjust without specialized equipment.

4. Distributor-Based Ignition Systems

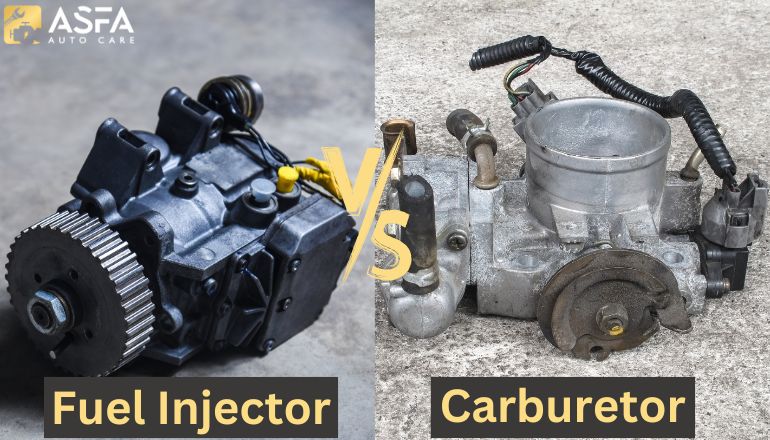

The distributor-based ignition system stands as another example of visible, mechanical engine management that EVs have rendered completely obsolete.

These devices represented an elegant mechanical solution to the challenge of delivering high-voltage spark to the correct cylinder at precisely the right moment.

A distributor’s rotating shaft, driven by the engine’s camshaft, physically directed electrical current to each spark plug in sequence, with the timing mechanically advanced or retarded based on engine speed and load using centrifugal weights and vacuum diaphragms.

The mechanical beauty of distributors lay in their purely physical operation. Inside the distributor cap, a rotor spun on the central shaft, making brief contact with terminals that connected to each spark plug wire.

Centrifugal advance mechanisms used spring-loaded weights that swung outward as engine speed increased, physically rotating the trigger point earlier to advance timing.

Vacuum advance units responded to intake manifold pressure, adjusting timing based on engine load. All of this happened through springs, weights, and diaphragms no computers, sensors, or electronics required.

For enthusiasts, distributors offered tuning opportunities. Performance enthusiasts could recurve distributors by changing springs and adjusting advance curves to optimize power delivery.

Point gap adjustments, dwell angle settings, and ignition timing with a timing light and wrench represented fundamental tuning skills.

The transparent, mechanical nature of distributors meant skilled mechanics could diagnose problems through observation worn distributor gears, burned points, corroded terminals, or cracked distributor caps were visible issues with straightforward solutions.

The ritual of tuning a distributor-equipped engine created a connection between the owner and the machine. Setting ignition timing involved connecting a timing light, loosening the distributor hold-down bolt, and physically rotating the distributor body while monitoring the timing marks on the harmonic balancer or flywheel a hands-on procedure that provided immediate feedback and required no specialized software.

Modern engines use electronic ignition with individual coil-on-plug designs controlled by engine computers that adjust timing thousands of times per minute based on dozens of sensor inputs.

This system delivers superior performance, reliability, and emissions control while enabling advanced features like cylinder deactivation and variable valve timing coordination. Electric vehicles eliminate ignition systems, as electric motors require no spark plugs, timing, or combustion management whatsoever.

While electronic and EV solutions are objectively superior, they’ve eliminated a layer of mechanical accessibility. The distributor’s operation could be understood by watching it work; modern ignition exists as invisible electronic signals that require diagnostic computers to comprehend.

Also Read: Top 8 Used Sports Cars Under $30K That Investors Are Quietly Chasing

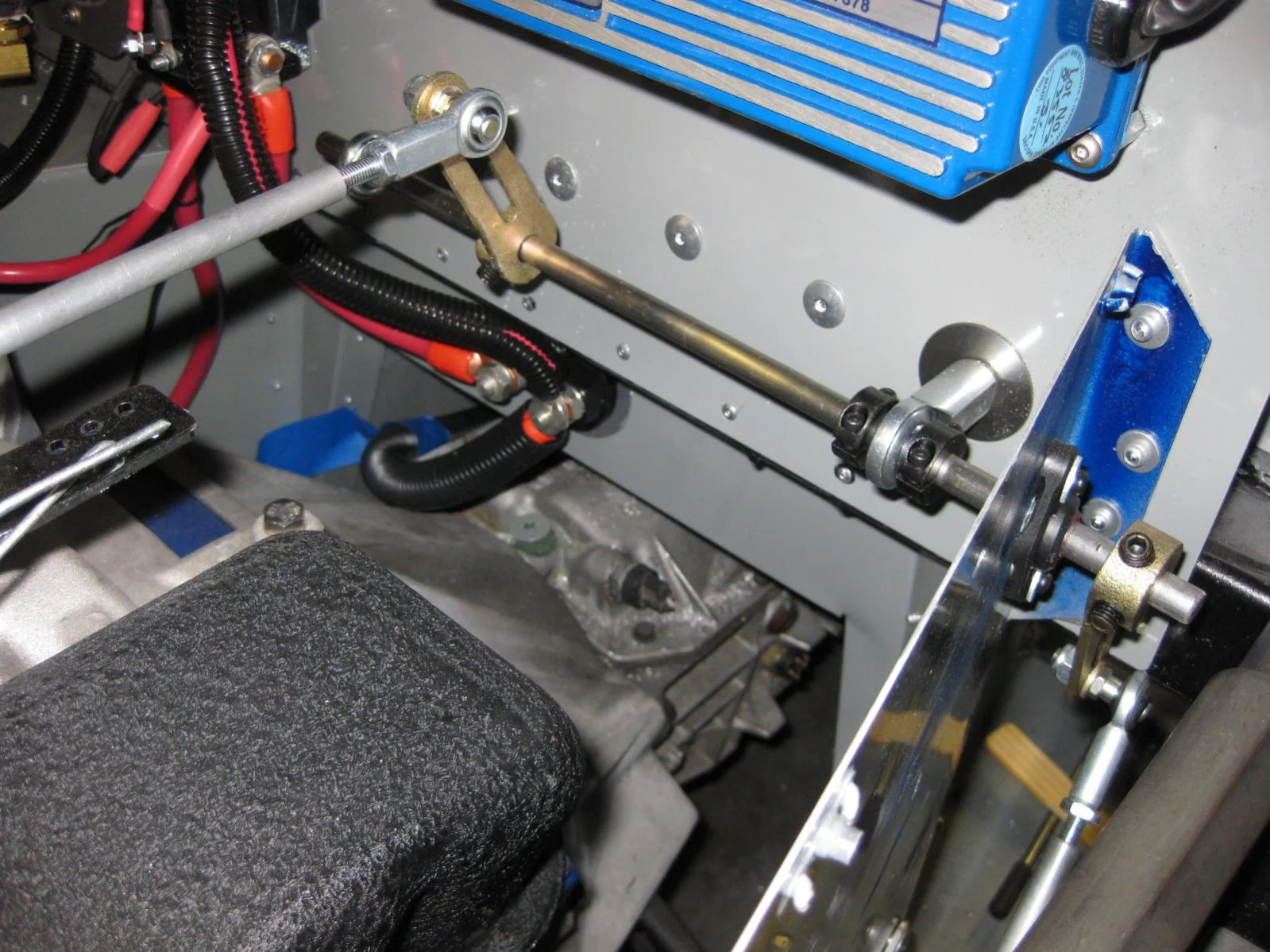

5. Mechanical Throttle Linkages

Before drive-by-wire systems became universal in the early 2000s, throttle control was achieved through purely mechanical linkages a direct physical connection from accelerator pedal to throttle body or carburetor.

When you pressed the gas pedal, you physically pulled cables or operated rods that opened the throttle butterfly valves, directly controlling airflow into the engine.

This direct mechanical connection provided immediate, linear response and genuine feedback that created an intuitive connection between driver input and engine output.

Mechanical throttle systems offered transparency in their operation. You could watch the throttle linkage move, see the butterflies open, and feel the cable tension through the pedal.

The system’s response was immediate and predictable press the pedal down, the throttle opens proportionally, and the engine responds. There was no delay, no interpretation, and no electronic intermediary between your foot and the engine’s air supply.

This direct connection provided valuable feedback. A sticking throttle cable made itself immediately known through pedal feel. Worn linkage bushings created perceptible slop.

The gradual increase in throttle opening created progressive, predictable power delivery that skilled drivers could modulate precisely. Performance drivers could feel exactly how much throttle they were applying, sensing the mechanical resistance and using it to make minute adjustments during challenging driving.

Mechanical linkages also offered adjustability. Enthusiasts could adjust cable tension, modify pedal geometry for a different feel, or install aftermarket pedal assemblies.

The mechanical simplicity meant repairs required only basic tools and common parts replacement cables, bushings, or return springs could be sourced easily and installed without diagnostic computers or dealer programming.

Modern drive-by-wire throttle systems use electronic sensors to detect pedal position and electric motors to open throttle bodies based on computer interpretation of driver intent.

These systems enable features like traction control, stability control, cruise control integration, and throttle mapping modes legitimate safety and convenience benefits. Electric vehicles take this further, eliminating throttles, replacing them with potentiometers that send signals to motor controllers.

However, drive-by-wire systems introduce noticeable delays as computers interpret inputs, potentially intervene for safety reasons, and command actuators.

The pedal feel becomes artificial, often simulated through spring resistance rather than actual mechanical resistance. Most frustratingly, the driver’s input becomes a suggestion rather than a command the computer mediates between intention and execution, sometimes overruling driver input entirely.

6. Unassisted Hydraulic Steering

Before power steering assistance became universal, and long before electronic power steering eliminated hydraulic systems, steering systems offered direct, unfiltered communication between the front wheels and the driver’s hands.

Pure manual steering, and later simple hydraulic assistance systems, transmitted every road surface detail through the steering column to the wheel a continuous stream of tactile information that skilled drivers used to understand grip levels, surface conditions, and vehicle balance.

Unassisted steering required genuine physical effort, particularly at low speeds or when stationary, but this effort was proportional and meaningful.

The resistance you felt corresponded directly to the forces acting on the front tires. When grip was plentiful, steering effort was moderate.

As grip decreased on ice, gravel, or at the limit of adhesion the wheel became lighter, communicating reduced traction. This direct feedback allowed drivers to sense the contact patch’s interaction with the road surface, feeling texture changes, identifying wet patches, or detecting the precise moment when tires began to slide.

Hydraulic power steering systems, when properly calibrated, maintain much of this feedback while reducing physical effort through hydraulic assistance.

A belt-driven pump pressurized fluid that helped turn the wheels, with assistance proportional to steering input. The best hydraulic systems those found in performance cars from manufacturers like Porsche, BMW, and Honda preserved road feel while making steering manageable.

Enthusiasts particularly praised these systems for their progressive buildup of weight and retention of detailed feedback. The mechanical simplicity of hydraulic steering also provided reliability and repairability.

Many modern performance cars are criticized for numb, over-assisted steering that communicates little about road conditions or grip levels, leaving drivers to rely on visual cues and vehicle behavior rather than steering feel to understand what the car is doing.

7. The Visceral Experience of Engine Vibration

Internal combustion engines are, by their fundamental nature, controlled explosions occurring dozens of times per second. This explosive process creates vibrations that resonate through the entire vehicle structure, sensations that communicate the engine’s mechanical operation in ways that go beyond sound.

These vibrations provided constant feedback about engine condition, speed, load, and character, creating a multi-sensory experience that engaged drivers beyond mere transportation.

Different engine configurations produced distinctive vibration signatures. Inline-six engines, with their inherently balanced design, delivered smooth operation even at high RPMs.

V8s, particularly American pushrod designs with their longer piston strokes, generated pulsating vibrations that synchronized with their deep exhaust notes.

Four-cylinder engines created more pronounced secondary imbalances that required balancer shafts to mitigate. These vibrations weren’t flaws they were characteristics that contributed to each engine’s personality.

Performance engines often emphasized these mechanical sensations deliberately. Italian exotics minimized sound deadening to preserve the raw mechanical experience.

British sports cars like classic Lotuses and Caterham Sevens transmitted nearly every vibration from the powertrain directly to the driver, creating an intense connection between human and machine. Even muscle cars, despite their focus on straight-line performance, created dramatic sensations as their powerful engines twisted their chassis under acceleration.

These vibrations served functional purposes beyond ambiance. Experienced drivers could detect mechanical problems through abnormal vibrations a missing cylinder created a pronounced shake, worn motor mounts transmitted excessive movement, and failing components often announced themselves through changes in vibration patterns before complete failure.

The lack of vibration contributes to EVs feeling more like appliances than involving driving machines, regardless of their impressive acceleration capabilities.

8. Analog Gauges and Mechanical Instrumentation

The instrument cluster once served as a driver’s direct window into the mechanical soul of their vehicle, with physical gauges using actual mechanical or electromechanical mechanisms to display information.

Before digital screens conquered dashboards, analog gauges used physical needles driven by stepper motors, magnetic movements, or even mechanical cables to communicate vital statistics.

These instruments weren’t just information displays they were precision mechanical devices that moved continuously, providing at-a-glance information through needle position and sweeping motion.

Classic instrumentation included mechanical speedometers driven by flexible cables connected to the transmission, with a spinning cable physically turning a magnet that moved the needle against spring resistance.

Tachometers measured electrical pulses from the ignition system, converting them to needle movement. Oil pressure gauges used physical tubes carrying actual engine oil to a bourdon tube mechanism that moved the needle.

Water temperature gauges employed bimetallic strips that bent with temperature changes. Voltmeters and ammeters displayed actual electrical system status through deflection of physical needles.

These analog instruments offered continuous information rather than discrete digital updates. A glance at gauge position provided immediate status the sweep of a tachometer needle communicated not just RPM but rate of acceleration, while an oil pressure gauge’s gradual movement told you how quickly the engine was warming up.

Performance enthusiasts particularly valued tachometers with bright redlines and clearly marked power bands, instruments that facilitated precise rev-matching and optimal shift points.

Higher-end vehicles featured additional mechanical gauges boost pressure for turbocharged engines, vacuum gauges for tuning carburetors, mechanical chronographs for timing, and even mechanical clocks with tiny mechanical movements.

These instruments represented miniaturized precision engineering, tiny machines housed in the dashboard that continued the vehicle’s mechanical theme into the driver’s immediate environment.

The reliability of mechanical gauges also deserves mention. A mechanical oil pressure gauge would continue functioning even with a complete electrical failure.

Cable-driven speedometers needed no electrical power. These instruments could be repaired rather than replaced, with replacement movements, needles, and faces available for restoration.

Modern vehicles, especially EVs, have replaced nearly all analog instrumentation with digital screens TFT displays, LCD panels, or OLED screens that simulate gauge faces or present information in configurable graphical formats.

While these digital displays offer flexibility, customization, and the ability to present vast amounts of information, they lack the mechanical authenticity and continuous motion of analog instruments.

Digital gauges update in steps rather than smoothly sweeping, and their backlighting can feel artificial compared to the illuminated faces of physical instruments.

9. The Engagement of Cold Starts and Warm-Up Rituals

Cold-starting a carbureted or early fuel-injected internal combustion engine, particularly in cold weather, represented a ritualistic interaction between driver and machine that required understanding, patience, and technique.

Unlike modern engines that start instantly regardless of temperature, or EVs that require no warm-up whatsoever, older vehicles demanded specific procedures that varied by temperature, humidity, and the individual engine’s quirks knowledge that created a personal relationship between owner and vehicle.

Carbureted engines required manual choke operation to enrich the fuel mixture for cold starting. The driver pulled a choke cable or knob that partially closed a valve in the carburetor, restricting airflow to create a richer fuel mixture that would ignite more easily in cold cylinders.

Too much choke and the engine would flood with excess fuel; too little and it wouldn’t start. After starting, the driver gradually reduced the choke as the engine warmed, listening to the engine speed and sound to determine the proper choke position. This process required attention and understanding each engine had its own preferences.

The warm-up period itself was a time of audible and perceptible change. Cold engines ran rough, with pronounced vibrations and irregular idle as tight tolerances and thick oil impeded smooth operation.

Fast idle mechanisms kept RPMs raised until operating temperature was reached. Drivers learned to wait for this warm-up period before demanding full performance, understanding that metal components needed to expand to proper clearances and oil needed to thin to optimal viscosity.

Winter starting in extreme cold created even more elaborate rituals. Some drivers kept engine block heaters plugged in overnight. Others knew their engines needed specific procedures perhaps pumping the throttle exactly twice before cranking, or holding the pedal at a particular position.

Diesel engines, particularly older indirect-injection designs, required glow plugs to preheat combustion chambers, with dashboard lights indicating when cranking should begin.

These procedures created stories and character. Every enthusiast has tales of coaxing stubborn engines to life on cold mornings, of learning their vehicle’s particular preferences, and of the satisfaction when the engine finally caught and settled into its warming rhythm.

This interaction fostered mechanical sympathy understanding that the machine had physical needs and limitations that required respect.

Modern fuel-injected engines start reliably in nearly any conditions, with computer-controlled systems managing all mixture and timing adjustments automatically.

Electric vehicles eliminate the entire concept of cold starts and warm-up periods their motors deliver full torque from the first moment, regardless of temperature.

While this reliability is objectively superior, it eliminates another opportunity for driver-vehicle interaction and the knowledge that came from understanding cold-start procedures.

10. The Art of Engine Tuning and Mechanical Modification

Perhaps the greatest loss in the transition to electric vehicles is the entire culture of mechanical engine modification and tuning generations of knowledge about extracting performance from internal combustion engines through physical modifications to mechanical components.

Carburetors could be rejetted, camshafts swapped for different profiles, compression ratios changed, porting and polishing performed, and countless other modifications made by skilled enthusiasts in home garages using hand tools, creating genuine performance improvements through mechanical understanding.

Performance modification represented accessible hot-rodding that required relatively simple tools and mechanical knowledge rather than expensive electronic equipment.

Enthusiasts learned about airflow dynamics by porting cylinder heads, understood thermodynamics through compression ratio calculations, and grasped mechanical physics by selecting camshaft specifications. This hands-on education created generations of mechanically literate enthusiasts who understood their vehicles at a fundamental level.

The modification process offered extensive creative freedom. Engine swaps placed different powerplants in inappropriate chassis. Forced induction added turbochargers or superchargers to naturally aspirated engines. Stroker kits increased displacement through longer crankshaft throws and larger bore dimensions.

These modifications produced tangible, measurable results increased horsepower, improved torque delivery, distinctive exhaust notes that rewarded the builder’s skill and investment.

The mechanical nature of these modifications meant they could be reversed, refined, or rebuilt. A poorly selected camshaft could be swapped for a better profile. Compression ratios could be adjusted by changing head gaskets or pistons.

Carburetors could be rejetted repeatedly until optimal performance was achieved. This iterative process taught valuable lessons about engine operation and tuning principles.

The social aspect of mechanical modification also deserves recognition. Enthusiasts shared knowledge in forums, magazines, and garage gatherings.

Experienced builders mentored newcomers, passing along hard-won knowledge about what worked and what didn’t. Specific combinations became legendary certain intake manifold and carburetor pairings, particular camshaft grinds for street performance, or optimal compression ratios for pump gasoline.

Electric vehicle modification exists, but primarily involves software calibration and battery management modifications requiring specialized electronic knowledge and equipment rather than mechanical skills.

EV motors can be replaced with more powerful units, but the modification lacks the extensive permutations possible with internal combustion engines.

There are no cam profiles to select, no carburetor jetting to perfect, no compression ratios to calculate. The electric motor’s inherent efficiency means fewer opportunities for meaningful performance extraction through mechanical means, and the complex battery management systems generally resist modification to protect battery longevity and safety.

Also Read: Top 10 V6 Classics That Never Needed Eight Cylinders