The history of the automobile is written not just in chassis numbers and body styles, but in the thunderous roar of iconic engines that defined entire generations of motoring.

These powerplants transcended their mechanical origins to become cultural touchstones, engineering marvels that captured the imagination of enthusiasts and casual drivers alike.

From the muscle car era’s displacement wars to European grand touring refinement, legendary engines represent the pinnacle of automotive achievement during their respective eras.

What raises an engine from merely competent to truly legendary? It’s a combination of revolutionary engineering, competition success, distinctive character, and lasting cultural impact.

These engines didn’t just move cars they moved entire industries forward, pushing boundaries of performance, efficiency, and reliability. They soundtracked movies, dominated racetracks, and created loyalists who would defend their chosen powerplant with religious fervor.

The greatest engines possess souls. They have personalities expressed through their power delivery, their soundtrack, and their quirks.

Whether it’s the mechanical symphony of a high-revving Italian V12, the thunderous torque of an American V8, or the precision of a German inline-six, these engines represent moments when engineering excellence met perfect timing.

They were often overbuilt, sometimes impractical, but always memorable created during an era when manufacturers prioritized character over cost-cutting and passion over pure profit margins.

This exploration celebrates those magnificent machines that earned their legendary status through innovation, performance, and an ineffable quality that makes them unforgettable decades after production ended.

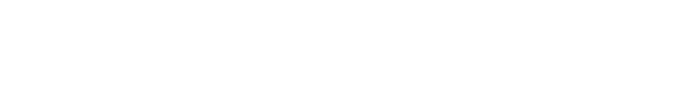

Chevrolet Small-Block V8

The Chevrolet small-block V8, introduced in 1955, stands as perhaps the most influential engine in automotive history. With over 100 million units produced across multiple generations, this compact, lightweight, and powerful design revolutionized American performance and became the backbone of hot rodding culture for generations.

The original 265 cubic inch design was revolutionary for its time, featuring a compact wedge combustion chamber, stamped steel valve covers, and advanced reverse-flow cooling.

Chief engineer Ed Cole’s team created an engine that weighed significantly less than competitors while producing impressive power.

The thin-wall casting technique used in the block allowed Chevrolet to achieve strength without excessive weight, an innovation that would influence engine design industry-wide.

What made the small-block truly legendary was its incredible versatility and tuning potential. From its introduction at 265 cubic inches, the engine family expanded to include 283, 302, 327, 350, and 400 cubic inch variants.

The architecture proved so fundamentally sound that hot rodders discovered they could reliably double or triple the factory horsepower figures with relatively simple modifications. The engine responded eagerly to performance upgrades, from mild camshaft swaps to full racing preparation.

The small-block powered everything from sedate Bel Air sedans to dominant Corvettes and Camaros. The fuel-injected 283 of 1957 became the first American production engine to achieve one horsepower per cubic inch.

The Z/28’s 302 dominated Trans-Am racing, while the 350 became one of the most ubiquitous engines ever produced, remaining in production until the early 2000s.

Beyond General Motors vehicles, the small-block’s compact dimensions, light weight, abundant power, and incredible aftermarket support made it the default engine for hot rodders, kit car builders, and engine swappers worldwide. You could find small-blocks in everything from Model A street rods to Jaguar E-Types to off-road buggies.

This universal adaptability created a self-reinforcing cycle: widespread use led to extensive aftermarket development, which led to even more widespread use.

The engine’s distinctive sound a smooth, muscular rumble that becomes a mechanical howl at high RPM became the soundtrack of American performance.

Even today, decades after the introduction of more advanced LS-series engines, the classic small-block remains cherished by enthusiasts who appreciate its combination of simplicity, reliability, and raw character that defined an era of automotive enthusiasm.

Ford Flathead V8

Ford’s flathead V8, introduced in 1932, democratized V8 power and launched the hot rod movement. Before its arrival, eight-cylinder engines were expensive luxuries reserved for premium automobiles.

Henry Ford’s vision of bringing V8 power to the masses created an engine that would reshape American automotive culture and become the foundation for an entire subculture.

The flathead’s side-valve design placed the valves beside the cylinders rather than overhead, creating a flat cylinder head that gave the engine its name.

While this configuration limited breathing and ultimate performance compared to overhead valve designs, it offered significant manufacturing advantages.

The engine was simpler to produce, more compact, and easier to maintain than contemporary overhead valve designs, allowing Ford to offer it in affordable models like the Model 18. Initially displacing 221 cubic inches and producing 65 horsepower, the flathead represented a quantum leap for affordable transportation.

Suddenly, working-class Americans could afford the smooth power and effortless cruising that V8 engines provided. The engine evolved throughout its production run, growing to 239 and eventually 255 cubic inches, with power outputs reaching into the triple digits.

What truly cemented the flathead’s legendary status was its adoption by hot rodders returning from World War II. These mechanically-savvy veterans had learned advanced engineering and fabrication techniques during the war, and they applied this knowledge to extracting maximum performance from surplus flathead engines.

The engine’s robust bottom end could withstand significant power increases, and its simple design made it easy to modify. The flathead’s distinctive appearance, with its wide, flat heads and prominent exhaust manifolds, became iconic.

Its sound a deep, burbling rumble quite different from later overhead valve V8s remains instantly recognizable. The engine powered countless dry lakes racers at Bonneville and El Mirage, establishing speed records and creating legends.

An extensive aftermarket industry developed around the flathead, with companies like Edelbrock, Offenhauser, and Weiand cutting their teeth producing performance parts for Ford’s V8.

These early speed equipment manufacturers would later dominate the entire performance parts industry, but they built their reputations on flathead parts.

Though Ford replaced the flathead with overhead valve Y-block engines in 1954, the flathead’s influence extends far beyond its production years. It represents the birth of performance automotive culture in America, the engine that proved working-class enthusiasts could build genuinely fast cars through ingenuity and determination.

Today, flathead-powered hot rods remain highly prized, with purists insisting that no other engine can provide the authentic experience of early hot rodding’s golden age.

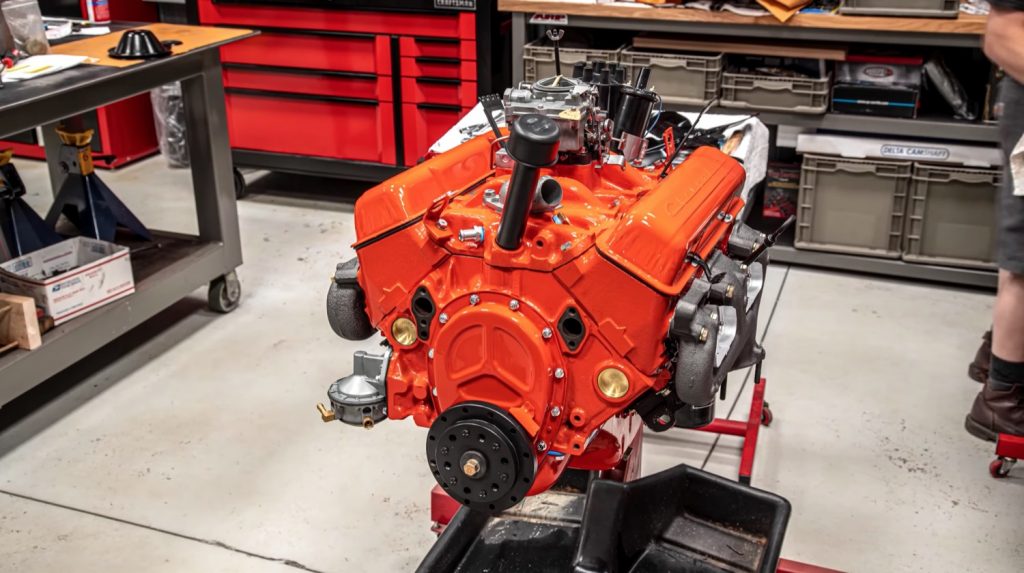

Ferrari Colombo V12

Gioacchino Colombo’s compact V12 design for Ferrari represents the pinnacle of romantic engine engineering. Introduced in 1947 in the 125 S, Ferrari’s first car, this engine family powered some of the most beautiful and successful sports cars ever created, establishing Ferrari’s reputation for engineering excellence and racing dominance.

The original Colombo V12 displaced just 1.5 liters, but its 60-degree architecture, single overhead camshaft per bank, and aluminum construction represented advanced thinking.

Colombo, who had previously designed successful engines for Alfa Romeo, created a powerplant that was compact, lightweight, and capable of high-revving performance characteristics that would define Ferrari V12s for decades.

The engine’s capacity grew steadily, reaching 3.0 liters by the late 1950s and eventually expanding to 4.4 liters in later evolutions. Each displacement increase maintained the fundamental architecture’s elegance while improving performance.

The Colombo V12 powered legendary competition cars including the 250 GTO, considered by many the greatest Ferrari ever built, and the 250 Testa Rossa, whose Pontoon-fendered bodywork became automotive art.

What distinguished the Colombo V12 was its character. The engine produced a mechanical symphony that remains unmatched a rising crescendo that began as a purposeful burble at idle, transformed into a aggressive howl in the mid-range, and culminated in a spine-tingling shriek at redline.

This wasn’t merely sound; it was music, with each cylinder firing contributing to a perfectly-timed mechanical orchestra. The engine’s construction quality matched its acoustic excellence.

Each V12 was essentially hand-assembled, with meticulous attention to detail ensuring that individual engines developed distinct personalities.

The sight of a Colombo V12 with its elegantly crafted cam covers, artfully designed intake manifolds, and beautifully finished components represented functional sculpture. These weren’t merely machines; they were expressions of Italian artistry applied to engineering.

The Colombo design’s racing pedigree was exceptional. It powered Ferraris to countless victories at Le Mans, the Mille Miglia, and Formula One World Championships.

The competition success wasn’t despite the engine’s elegant design but because of it the lightweight construction and compact dimensions gave Ferrari chassis engineers freedom to create brilliantly-balanced racing cars.

Road-going versions like the 250 GT California and 275 GTB brought this racing heritage to fortunate customers who demanded ultimate performance with sophisticated refinement.

The Colombo V12 remained in production through 1988, an remarkable 41-year run that saw the design evolve while maintaining its essential character a testament to the fundamental brilliance of Colombo’s original vision.

Also Read: 10 Coupes That Can Rack Up 500,000 Miles Without Breaking a Sweat

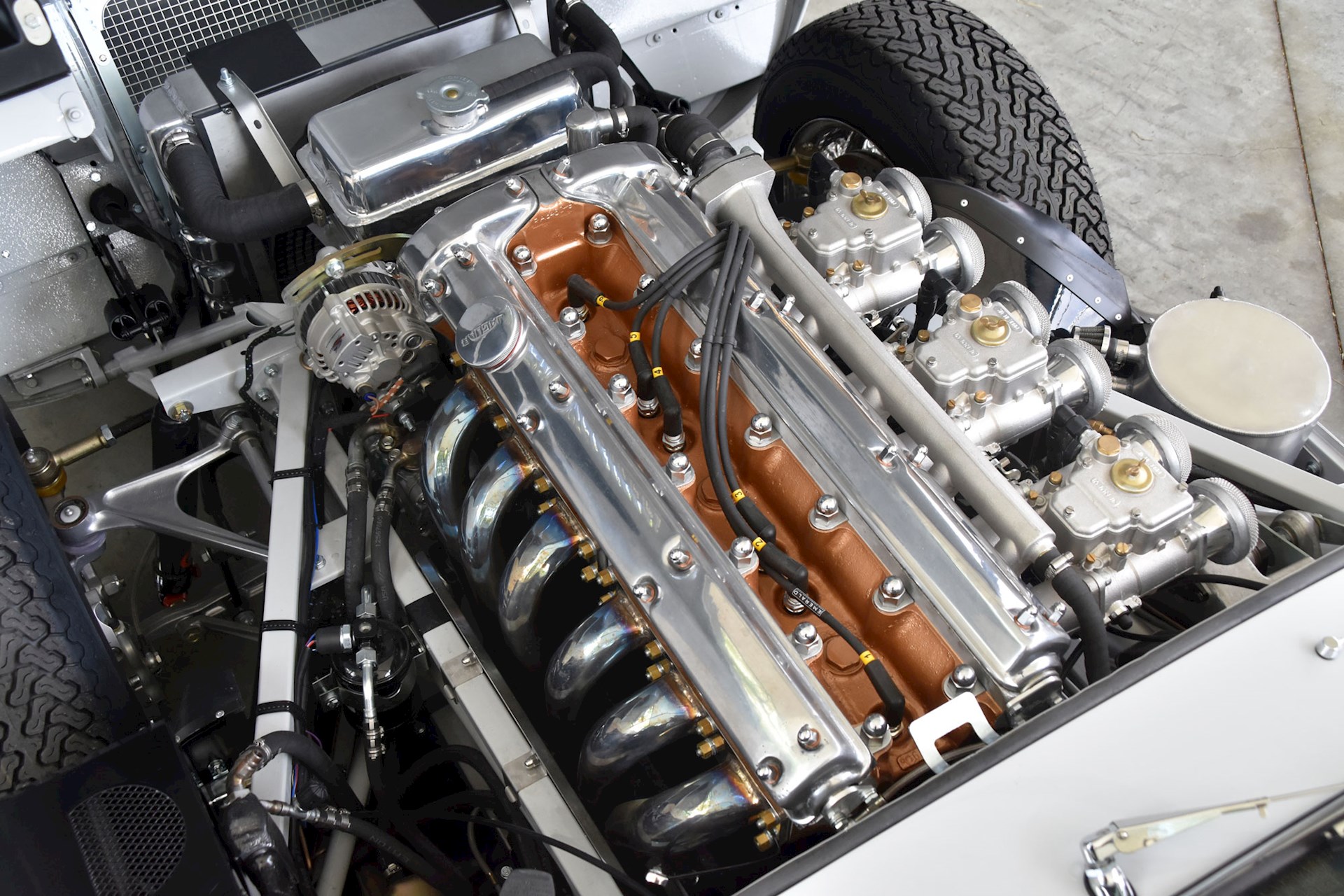

Chrysler 426 Hemi

The Chrysler 426 Hemi represents American muscle at its most fearsome. Introduced for racing in 1964 and offered in street form from 1966-1971, this engine became legendary for its brutal power and domination of drag strips and NASCAR superspeedways.

The distinctive hemispherical combustion chambers that gave the engine its name and its signature valve covers became icons of the muscle car era.

Chrysler’s engineers developed the Hemi specifically to dominate NASCAR, where Ford’s dominance had become embarrassing for Mopar.

The hemispherical combustion chamber design, which Chrysler had used in earlier Firepower engines, offered significant advantages.

The design allowed for larger valves positioned opposite each other, improving breathing dramatically. Combined with a high compression ratio, the result was an engine that produced staggering power 425 horsepower in street trim, though racers knew the actual output was significantly higher.

The Hemi’s NASCAR debut was devastating. In 1964, Hemis won 26 out of 32 races, prompting competitors to lobby for its banning. When Chrysler offered street versions in 1966, installed in Plymouth Belvederes and Dodge Coronets, the Hemi’s legend expanded beyond professional racing.

These street Hemis were barely civilized racing engines, with their aggressive camshafts creating rough idles and poor low-speed manners, but their performance was shocking even by modern standards.

The engine’s construction was robust to the point of being overbuilt. Massive cross-bolted main bearing caps, forged internals, and generous cooling passages meant the Hemi could withstand punishment that would destroy lesser engines.

Drag racers discovered they could reliably extract 600, 700, even 800 horsepower from street Hemi blocks with appropriate modifications, establishing the engine’s reputation as the ultimate foundation for serious performance builds.

What truly raised the Hemi to legendary status was its rarity and cost. The street Hemi was expensive about $800 over a standard engine, significant money in 1960s dollars.

This premium, combined with poor fuel economy and challenging driveability, meant relatively few were sold. Plymouth moved only about 11,000 Hemi engines during the street Hemi’s production run, creating immediate collectibility.

The Hemi powered iconic muscle cars including the Plymouth Road Runner Superbird, Dodge Charger Daytona, and the legendary ‘Cuda. Its distinctive valve covers, adorned with “426 Hemi” badges, became symbols of ultimate performance.

The engine’s deep, aggressive exhaust note was unmistakable a sound that promised violence and delivered it without hesitation. Today, original Hemi cars command astronomical prices, with pristine examples selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars, testament to an engine that defined an era’s performance aspirations.

Porsche Flat-Six

The Porsche flat-six engine, introduced in the 911 in 1963, represents evolutionary perfection. While other manufacturers experimented with various configurations, Porsche refined its air-cooled, horizontally-opposed six-cylinder design across five decades, creating one of the most characterful and successful engine families in automotive history.

Ferry Porsche’s decision to develop a flat-six rather than continuing with the four-cylinder engines used in the 356 was driven by the desire for smoother power delivery and increased displacement potential.

The original 2.0-liter engine produced 130 horsepower, modest by today’s standards but sufficient to make the 911 genuinely quick. More importantly, the engine established characteristics that would define Porsche performance: willingness to rev, distinctive sound, and remarkable reliability.

The flat-six’s air-cooled design, with individual finned cylinders and a large cooling fan, created packaging challenges that Porsche turned into advantages.

The engine’s compact dimensions allowed it to be placed behind the rear axle, creating the 911’s distinctive weight distribution and handling characteristics.

This layout, combined with the engine’s relatively light weight, contributed to the 911’s unique driving dynamics simultaneously challenging and rewarding.

As the 911 evolved, so did the flat-six. Displacement grew from 2.0 to 2.2, 2.4, 2.7, 3.0, 3.2, and eventually 3.6 liters in air-cooled form.

Each increase was carefully engineered to maintain reliability while improving performance. The introduction of turbocharging with the 930 Turbo created a legend within a legend an engine whose explosive power delivery and distinctive wastegate whoosh defined 1980s supercar performance.

The flat-six’s sound became as iconic as its performance. The distinctive mechanical clatter at idle, rising to an increasingly urgent howl as revs climbed, was unmistakably Porsche.

Air-cooled flat-sixes produced a unique acoustic signature part mechanical symphony, part industrial thrash that enthusiasts found addictive. This sound, combined with the engine’s transparency and willingness to rev freely, created an intimate connection between driver and machine.

Porsche’s racing success with the flat-six is extraordinary. The engine powered 911s to countless victories at Le Mans, the Targa Florio, and Daytona.

In turbocharged form, it propelled the fearsome 917/30 Can-Am car, which produced over 1,500 horsepower, making it one of the most powerful racing cars ever built.

The 911 GT1’s flat-six won Le Mans in 1998, proving that Porsche’s fundamental design remained competitive against purpose-built prototypes.

Though Porsche switched to water-cooled flat-sixes in 1998, the air-cooled engines remain deeply cherished. Their mechanical simplicity, distinctive character, and racing pedigree create devoted followings, with pristine air-cooled 911s commanding premium prices that continue climbing as enthusiasts recognize these engines represent a unique chapter in automotive history.

Also Read: 10 Affordable Mercedes Models That Become Expensive Headaches