“A rigorous process.” So says Dave Robson, the Williams Formula 1 team’s head of vehicle performance, of the process for deciding the Autosport Williams Engineer of the Future Award. This prestigious contest was much revamped for 2023, following its return last year after a pandemic-enforced hiatus.

The winner of that Award, Michael Preston, turned judge this year to help whittle down a field of over 200 initial candidates, which, for the first time, was open to anyone currently studying an engineering degree at any university or college in the UK.

The Williams team itself went over the application field to get that down to 60 contenders before sending 20 to an assessment day involving Williams’s Esports team, where Preston is now the chief engineer, as well as working in the Formula Regional European Championship by Alpine and Eurocup-3 series. The most promising 10 budding engineers then made the final selection for the full eight-month process.

They initially stayed working in the virtual world through April and May, helping the Williams Esports squad in various competitions around their studies and work placements. This included a win in the 2023 iRacing Nurburgring 24 Hours. At the end of this four-month stint, the field was again slimmed down. Now, just five candidates remained.

This group returned to Williams’s Grove headquarters for two assessment days in early September regarding F1 race strategy and driver-in-the-loop (DIL) simulator work. Robson, overseeing the race strategy tasks, reckons “a decent friendship” had evolved between the candidates, which he believes added “a nice dynamic of friendly rivalry” to the whole process.

But, as with the brutal world of professional sport, only the best would progress – the field finally settled at two finalists: David Crespo and Riccardo Calzetta. Entering the process, Crespo was a Motorsport Engineering Master’s degree student at Oxford Brookes University, while Calzetta was an Aeronautical Engineering MEng student at the University of Glasgow.

The finalists had two challenges remaining. The first was to attend a race weekend in the GB3 single-seater series, working with the Rodin Carlin squad at the Zandvoort round in October. They were chiefly asked to work through video and driver performance-related items for the team’s racers: Costa Toparis, John Bennett, and Callum Voisin.

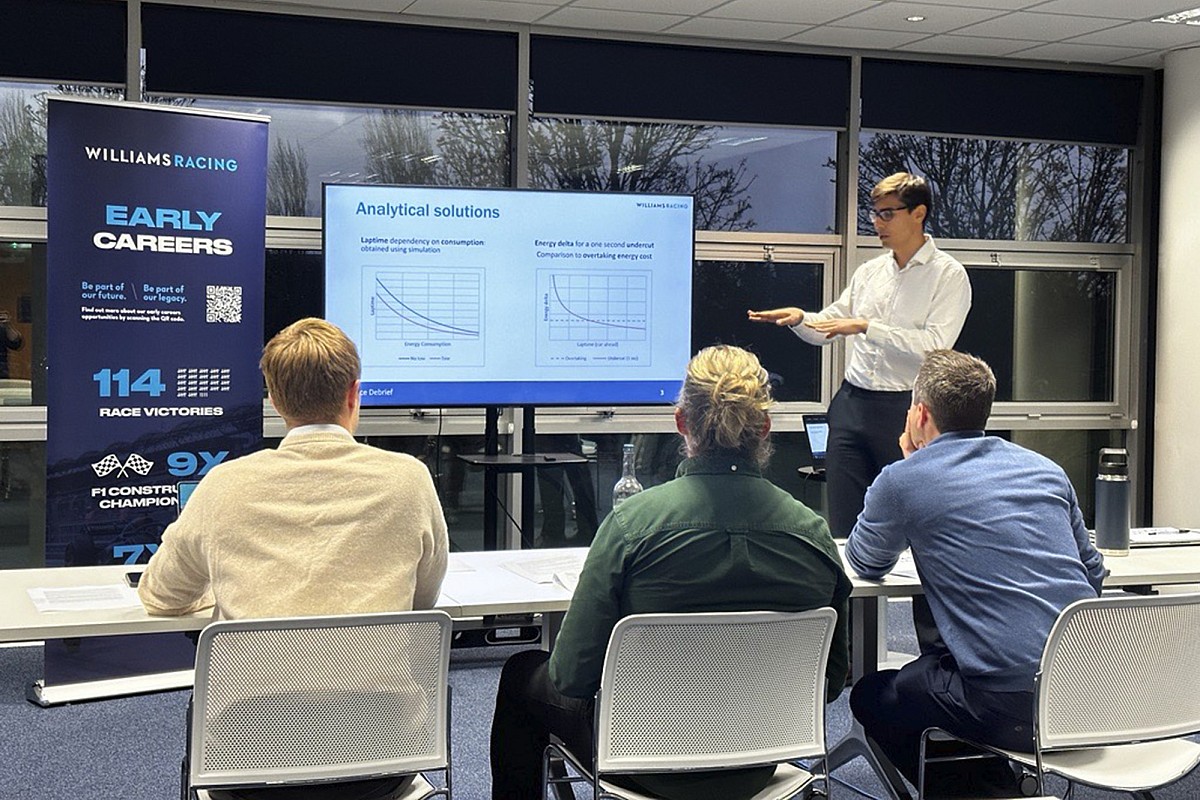

The second and final element of the whole process was to give a presentation in mid-November on a hypothetical motorsport-related engineering problem (in F1 or any other championship) within their domain experience. Their 15-minute talk had to explain how they would solve that problem and the expected results of their work. Crespo presented a new Formula E race strategy model, while Calzetta looked at the recent studies conducted by the FIA on fitting wet-weather wheel guards to F1 cars to reduce spray in rainy conditions.

To assess these presentations, Robson and Preston were joined by fellow judges Jamie Green (Williams’s Head of Talent Acquisition) and Alex Kalinauckas (Autosport’s Grand Prix Editor). Once both finalists had answered questions on their presentations, the judges convened and went over notes taken from the 15-minute performances, plus those provided by the other members of the judging panel. These were Williams DIL team leader Andrew Newton, who oversaw the simulator assessment, and famed single-seater team boss Trevor Carlin.

Three weeks later, the winner – Crespo – was revealed on stage at the 2023 Autosport Awards in London.

The factor critical in Crespo’s win was his combined presentation efforts across two specific elements of the process

“I’m really happy,” he says now. “It took me a lot of long hours and libraries and studying and working as hard as I could to be what I am today. But at the same time, I know I need to keep pushing as much as I can – keep improving for what’s to come, which I’m sure is going to be really exciting.”

“It was a really good process to be involved with,” reflects Robson. “A good opportunity to see [young engineers] in action and also put them under a little bit of stress and see how they cope in a way you can’t normally do.”

But, in what was a very close competition with Calzetta, the factor critical in Crespo’s win was his combined presentation efforts across two specific elements of the process. His ambition to delve into a totally new motorsport problem in the final presentations counted in his favor, but it was his thoroughness that ran throughout this and the F1 race simulation task that ultimately proved decisive.

That challenge was to produce a race strategy for a virtual driver to complete a race at Suzuka based on basic tire model information provided one month ahead of time and make a presentation – as the Williams team would do for its F1 drivers – for what was expected to happen, then race engineer the contest against the four other candidates at that stage and 15 other ‘cars’ controlled by Williams’s AI system, and sit a written test.

“We took them into the ops room in Grove, and they raced each other, basically,” Robson explains. “They could either follow the strategy they had presented, or they could deviate once they’d seen what other people were doing. And then, at the end of that, we got them all together and did a sort of review of how everyone’s strategies had gone.

“David undoubtedly had taken the data we’d sent them and done the most with it. So, his pre-race plan was extremely good. The way he presented it was also very good. He executed well. But I think the most impressive thing about him was the preparation he’d done, which is really what race strategy is all about.”

Robson and co felt Crespo’s pre-race planning had the verbal communication cues drivers need to understand strategy briefings, while critically, he was the only candidate to use the correct methodology for calculating tire degradation. He says he “tried to pretty much cover all the possibilities” in his race strategy arrangement while understanding “it’s impossible to cover literally everything that will happen.”

“But at least I brought a range of the most likely possibilities,” he adds. “It proved how brutal races can be – because I did all that work, and then when we were doing the race, there was a safety car just when I didn’t want it. So, I had three worst-case scenarios in which I’d be basically f***** with my strategy – and one of them happened! But that’s racing, and they appreciated that.”

Robson concludes that “in the end, the two guys were very close”, but overall, throughout the whole process, he says, “David just showed that little bit more skill at interpreting what we’d asked them to do and then executed it extremely well, plus the presentations.”

Heading into 2024, Crespo is working for the ERT Formula E squad. As part of his Award win, Crespo will also attend an F1 test day with Williams in 2024, supporting its trackside engineering team. He said on stage at the Awards ceremony in early December, “I want to be the engineer of the present, not the engineer of the future,” but also echoed Robson’s feelings on the friendship established in the 2023 Award process.

“The very first day when we went to Williams for the first time, Riccardo was the first person I talked to,” Crespo says of Calzetta. “We got along very well, and over the stages, we kept in touch, and we kept talking. I think we’ve got a lot in common, and one of the things I took from the entire process is friendship. It’s been a nice surprise!”

The engineering problem of limited track time

There has been much discussion about the impact of reduced track running for junior drivers in recent years, but what about the knock-on effect on young engineers? Williams’s head of vehicle performance, Dave Robson, shares his thoughts.

“I think getting the foot in the door is no different,” he says. “Other than that, the teams are bigger and are more switched on about graduate recruitment than perhaps they were 25 years ago when they were much smaller operations.

“But I think getting a trackside job, getting that experience, is different. I was lucky that I started a factory job [with McLaren] and then was able to join the test team when we had a full test team. You could get a lot of really good track experience that way. Now, obviously, we don’t have any of that anymore. Every time the car runs on track, it has to be done properly in a full, professional operation. So, I think for people trying to find some track experience in other formulas, perhaps it is more important than it was if you actually want to get into a trackside role.

“That said, equally, it’s more difficult for us [at F1 teams] to find the people we need to fill the trackside roles. So, that’s definitely a problem.

“It’s not much different to what you see with the junior driver stuff. It’s the same dilemma – how do you get the next generation of Formula 1 drivers in and prepared to a suitable level [when track time in junior formulas is now more limited]? And I think for the engineers, it’s no different. There’s much less opportunity. So, between the candidates’ own initiative and probably us as a sport, we need to think a little bit more about how we do that going forward.”