The Cold War era, marked by an intense standoff between the Soviet Union and the West, was a time of unrelenting paranoia, monumental engineering feats, and obsessive preparation for global catastrophe.

It was a period when the possibility of nuclear war wasn’t just a distant threat — it was a pressing reality that shaped every aspect of defense, industry, and infrastructure.

Amidst this geopolitical climate, the Soviet Union undertook massive efforts to develop machinery that could withstand not just the harshest climates on Earth but potentially the fallout of World War III.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this doomsday-ready arsenal was a series of engines — powerful, durable, and astonishingly overbuilt — designed to function under post-apocalyptic conditions.

These engines, created for tanks, aircraft, power plants, and even mobile nuclear missile carriers, were designed not for efficiency or elegance, but for sheer survival.

They were crafted with resilience in mind, able to operate with low-grade fuel, extreme temperature swings, and minimal maintenance.

Their purpose wasn’t to compete in a consumer market or win innovation awards; it was to ensure that the Soviet military-industrial complex could keep moving, breathing, and striking — even after a nuclear exchange.

Though much of the West focused on advancing digital technologies and precision weaponry, the USSR poured resources into engineering that embraced brutalism and raw power.

Today, many of these engines are forgotten relics, rusting in hangars, bunkers, and military scrapyards. But their stories remain potent reminders of a world teetering on the brink, and the lengths to which humanity will go to prepare for the end.

In this article, we dive into some of these extraordinary machines — engines that were built not just to run, but to survive the end of civilization itself.

Also Read: Why Some Engines Were Designed to Break (And Others Never Do)

The V-2 Diesel Tank Engine: A Warhorse Reimagined for the End Times

One of the most iconic Soviet engines, the V-2 diesel engine, was initially developed for the legendary T-34 tank during World War II. However, its legacy didn’t end in 1945.

The Soviets recognized the V-2’s unmatched reliability and simplicity, and they kept modifying it well into the Cold War era.

It became a foundational component for newer tanks like the T-55, T-62, and even the T-72 — all of which were designed to remain functional in contaminated, post-nuclear environments.

The V-2’s key to survival was its rugged simplicity. Made from aluminum for weight savings and capable of operating on a range of fuel types, including kerosene and low-grade diesel, it didn’t require the pristine conditions that Western engines often demanded.

In tests, tanks equipped with the V-2 were submerged, frozen, and operated in radioactive zones — and the engines kept running. They weren’t just tools of war; they were engines meant to carry civilization (or what remained of it) through the ashes.

The GTD-1250: A Jet Engine for a Tank

Another Soviet marvel was the GTD-1250 gas turbine engine used in the T-80 tank. Inspired by jet engines used in aircraft, this powerplant was built to deliver 1,250 horsepower, giving the T-80 unmatched acceleration and mobility for a vehicle of its weight.

While NATO was developing diesel-powered tanks with long logistical chains, the Soviets opted for turbine technology that could cope with a wider range of environments and fuels.

Why would a gas turbine be apocalyptic-ready? For one, turbines can start faster and operate more smoothly in freezing conditions, a real advantage in the Siberian steppes or after a nuclear winter.

Second, the GTD-1250 was designed with modularity in mind — it could be replaced in under an hour, even in field conditions. Additionally, its ability to run on kerosene, diesel, or even aviation fuel meant that in a resource-scarce, post-war world, the engine could adapt.

Though criticized for being fuel-hungry, the GTD-1250 wasn’t designed for efficiency. It was designed to move tanks fast, far, and with minimal support in the most hellish circumstances imaginable.

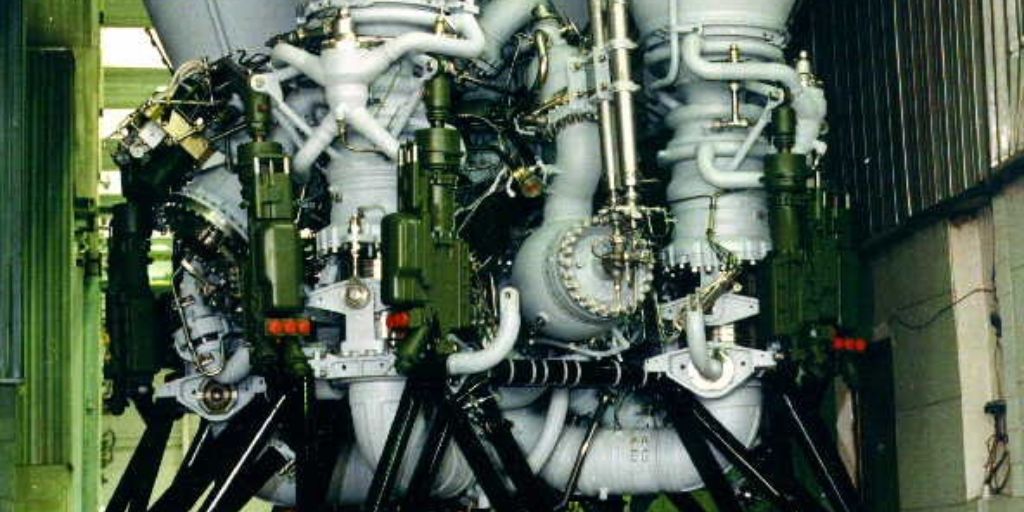

RD-170 Rocket Engine: Built for the Heaviest of Payloads

While not designed for everyday vehicles, the RD-170 rocket engine was a behemoth intended for the Energia launch vehicle and the ill-fated Buran space shuttle.

Unlike American counterparts that prioritized reusable systems and lightweight designs, the RD-170 embraced brute force. With over 1.6 million pounds of thrust, it remains the most powerful liquid-fueled rocket engine ever built.

What makes the RD-170 apocalyptic isn’t just its size — it’s its capability to launch massive payloads into orbit quickly, and its robust build.

The Soviets envisioned scenarios in which satellites or even weapons platforms would need rapid deployment during a nuclear confrontation.

This engine could carry heavy-duty modules, mobile command centers, or strategic deterrents into space even if ground facilities were compromised.

Moreover, the RD-170’s descendants are still in use today, testifying to their foundational strength. They were built during an era when failure meant national embarrassment — or strategic disaster.

The Ural Diesel Engines (D-12A and Beyond): Indestructible Workhorses

The Soviet Union’s logistics depended heavily on trucks, trains, and utility vehicles powered by the Ural family of diesel engines. One such example is the D-12A, which powered locomotives, submarines, and even portable generators.

These engines were specifically engineered to be field-serviceable — an essential quality in a post-disaster scenario where skilled mechanics and replacement parts would be scarce.

D-12 variants could operate in harsh conditions, withstanding sub-zero temperatures, dusty environments, and high radiation.

The Soviets also developed water-cooled versions that could continue running even when traditional cooling systems failed. For military trains and mobile missile platforms — vital in maintaining second-strike capabilities — these engines were a strategic lifeline.

Unlike sleek Western designs focused on performance-per-pound, the Ural diesels were ungainly, loud, and built like tanks. And like tanks, they just kept going.

The MAZ-547 Power Units: Movers of Titans

No discussion of apocalyptic engines would be complete without mentioning the MAZ-547 transporters — massive, 12-wheeled vehicles used to carry intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). These vehicles required complex and highly durable powerplants to haul nuclear warheads over unpaved roads and frozen wilderness.

The MAZ trucks were powered by dual V12 diesel engines, with massive torque and synchronized power delivery. They needed to operate independently, without the luxury of external support or paved infrastructure.

Even if roads were destroyed, bridges collapsed, or cities leveled, these engines ensured that mobile missile launchers could still reach their launch zones.

In a nuclear war scenario, survivability depended on mobility. Fixed silos were vulnerable to first strikes, but mobile ICBM launchers could evade detection. Thus, their engines weren’t just mechanical — they were existential tools of deterrence.

The NK-33: Forgotten, Then Resurrected

Originally developed in the 1960s for the N1 lunar rocket program — the Soviet counterpart to NASA’s Saturn V — the NK-33 engine was ahead of its time. Compact, efficient, and immensely powerful, it featured innovations such as an oxygen-rich staged combustion cycle, which the West wouldn’t match for decades.

Though the N1 rocket failed multiple times and the lunar program was scrapped, hundreds of NK-33s were mothballed in warehouses.

Decades later, engineers were astonished to find that these engines still worked with minimal refurbishment. Their quality, precision, and performance rivaled or exceeded modern equivalents.

In a post-apocalyptic world where retooling production lines could take decades, having a stockpile of rocket engines that still function is nothing short of miraculous.

The NK-33 is a testament to forgotten excellence — and a reminder that sometimes, the best engineering lies dormant until it’s needed most.

Nuclear-Powered Engines: The Soviet Dream That Almost Was

Perhaps the most apocalyptic of all Soviet engine concepts were those involving nuclear propulsion. The USSR experimented with nuclear-powered aircraft and missile systems, including the infamous Project Pluto-like cruise missiles that could loiter indefinitely in the air thanks to onboard nuclear reactors.

Though these projects never became operational due to safety concerns and technical difficulties, the ambition itself speaks volumes.

In theory, a nuclear-powered bomber or drone could fly for weeks without refueling, circumventing global air defenses and surviving the collapse of infrastructure.

The Soviets envisioned a future where combustion-based logistics might fail, but nuclear-powered vehicles could still roam the Earth — or skies.

These designs never made it past the prototype stage, but their mere conception reveals the radical lengths the USSR was willing to go to survive and dominate in a post-apocalyptic reality.

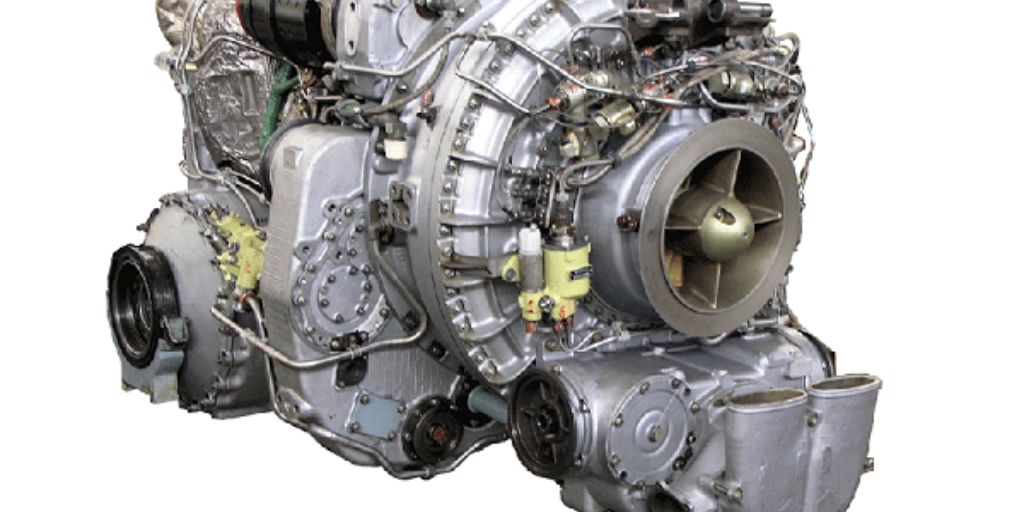

Zvezda M503: The Colossal Marine Engine

One of the most extreme examples of Soviet overengineering was the Zvezda M503, a marine engine so massive and complex that it looks more like a science fiction artifact than a real-world machine.

Designed originally for Soviet fast attack boats and missile corvettes, the M503 is a 42-cylinder radial diesel engine, organized into seven banks of six cylinders. It produces over 4,000 horsepower, and its main selling point was its ability to keep going even when partially damaged.

Why would such an engine be considered apocalyptic-grade? First, it was air-start capable, meaning it didn’t rely on fragile electrical systems.

Second, the radial layout ensured that if one bank of cylinders failed due to damage or overheating, the engine could still function on the remaining banks.

This redundancy made it ideal for high-stakes military operations in potentially irradiated, electromagnetically disrupted environments — exactly what a post-nuclear landscape would look like.

Even decades later, a few M503 engines have been restored by enthusiasts and fired up, showcasing their staggering endurance and visceral power.

While most of the West abandoned radial marine diesels long ago, the Soviets clung to the idea of mechanical superiority through complexity — a strategy that, while controversial, certainly left a mark.

The TM-170 Mobile Nuclear Reactor: Power in a Box

Though less well known, the Soviet Union developed mobile nuclear power stations like the TES-3, mounted on T-10 tank chassis. These units were designed to provide electricity in remote, devastated, or militarized zones — especially where conventional fuel supplies were disrupted.

The mobile reactor’s engine system wasn’t just for propulsion; it was part of a mobile infrastructure plan to bring power to front lines or disaster zones.

These self-contained mobile reactors could power entire field hospitals, command centers, or even radar systems in the event of a total blackout.

The engine units driving the TES-3 were fortified against radiation, EMPs, and thermal shock, making them some of the most robust auxiliary systems ever designed.

Although few were built and fewer still deployed, they embody the ultimate apocalyptic logic — if the world ends, bring your own power plant.

The Soviet Union’s obsession with resilience, redundancy, and raw power birthed some of the most formidable engines the world has ever seen.

While Western engineers focused on refinement and innovation, Soviet designers worked under the assumption that their machines might someday operate in a shattered world — devoid of supply chains, service networks, or safety. Their engines weren’t built for comfort or convenience; they were built for survival.

Today, many of these machines lie dormant — rusting in scrapyards, stored in forgotten depots, or powering legacy systems still running in remote parts of the world.

They represent a unique period in history where engineering was driven not by market demands but by existential fear.

These engines were symbols of defiance against chaos, embodiments of a strategy that hoped to outlast annihilation.

As we reflect on the Cold War era, it’s tempting to dismiss such creations as overkill or relics of paranoia. But their existence serves as a reminder of humanity’s unmatched capacity to innovate under pressure — and its terrifying readiness to prepare for the worst.

In an age increasingly dominated by sleek, smart, and disposable technology, the enduring legacy of Soviet apocalyptic engines challenges us to rethink what durability and preparedness really mean.

These engines may never roar to life again, but their story isn’t over. They remain testament to a forgotten philosophy of engineering — one where survival wasn’t just a possibility but a priority. And in a world that still teeters on geopolitical uncertainty, perhaps their lessons shouldn’t be forgotten after all.

Also Read: Engines That Can Run for 500 Hours Without an Oil Change