Few automotive origin stories are as surprising and yet so logically intertwined as those of engines born in agricultural machinery and later repurposed for cars.

It might seem counterintuitive that a powerplant designed for plowing fields, pulling heavy loads at low speeds, and enduring the harshest conditions would make for an ideal road-going engine.

Yet, throughout automotive history, several manufacturers have successfully leveraged the durability, torque characteristics, and straightforward maintainability of tractor engines to meet the demands of passenger vehicles, taxis, off-roaders, and even high-performance machines.

Tractor engines are built for one primary purpose: reliability under constant strain. They idle for hours, work at low RPMs in thick mud, and must be serviceable by mechanics in remote locations without sophisticated tools.

These attributes — robustness, torque delivery at low revs, and simplicity — also resonate strongly in automotive applications where longevity, fuel efficiency, and ease of repair are valued above outright speed.

This article delves into six illuminating case studies of engines that made the leap from tractors to cars.

We’ll explore the Lamborghini V12’s philosophical roots in Ferruccio’s Trattori business, Perkins’ diesel workhorses in iconic British and Indian steel, Ford’s Flathead V8 resonance in hot-rodding culture, International Harvester’s Scout propulsion, Mercedes-Benz’s OM diesels in immortal taxi fleets, and Fiat’s compact tractor lineage in the Fiat 500 city icon.

Together, these examples illustrate how agricultural engineering shaped automotive history in unexpected ways.

Also Read: Why Some Engines Are Still Hand-Assembled Today

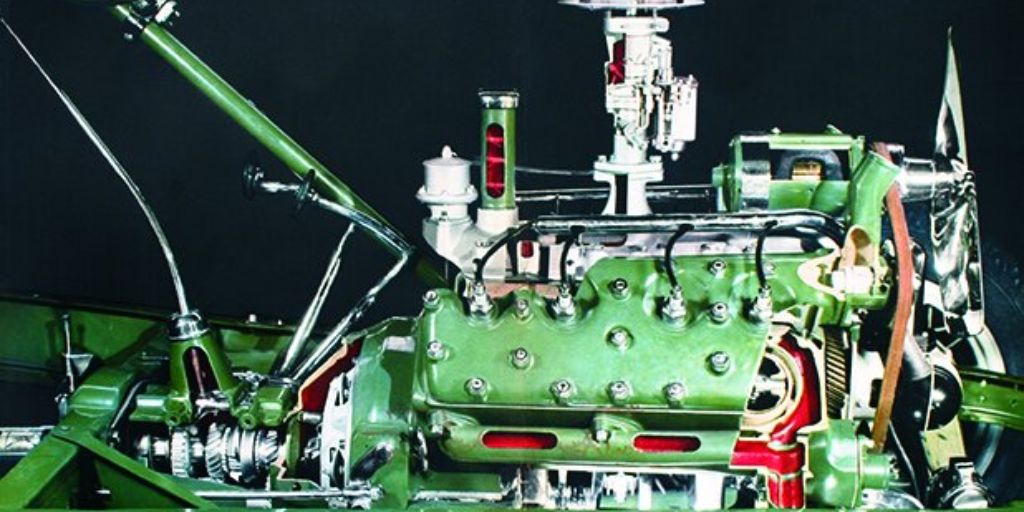

Lamborghini V12 – From Tractors to Supercars

Ferruccio Lamborghini began his industrial journey in 1948 with Lamborghini Trattori, crafting tractors from military surplus engines and truck components.

Purpose-built for torque and durability, these powerplants shared a common mechanical ethos: straightforward design, robust iron blocks, and ease of maintenance in the field.

When Ferruccio challenged ex-Ferrari engineer Giotto Bizzarrini to produce an automotive engine for the new 350GT, he demanded those tractor-engine virtues alongside smooth power delivery.

Though the resulting 3.5‑liter V12 was bespoke for performance, it mirrored Lamborghini’s agricultural roots. Its wide V‑angle, single‑camshaft-per-bank layout, and prioritized low‑end torque harked back to tractor requirements.

Over successive generations — from the Miura’s transverse-mounted V12 through the Countach’s high-revving iterations to the Diablo and Murciélago — Lamborghini retained the fundamental block architecture. The combination of reliability and mechanical accessibility meant that even exotic supercars could be serviced with minimal specialized tooling.

Beyond mechanical lineage, Lamborghini’s tractors shaped corporate culture. Early test mules reportedly used heavily reinforced tractor frames, and design choices such as easily removable cylinder heads or external timing chains continued the theme of field‑serviceability.

While these details are often overshadowed by flashy bodywork and high redline figures, the tractors’ DNA is indelibly stamped in Lamborghini’s V12 lore.

In a broader sense, Ferruccio’s success illustrated that a focus on durability and user‑serviceability — honed in agriculture — could underpin iconic performance engines.

The Lamborghini V12 remains in production, in heavily evolved form, more than seven decades after its tractor-inspired genesis, attesting to the strength of blending workhorse practicality with high-performance ambitions.

Perkins Diesel – British Workhorses Go Road Legal

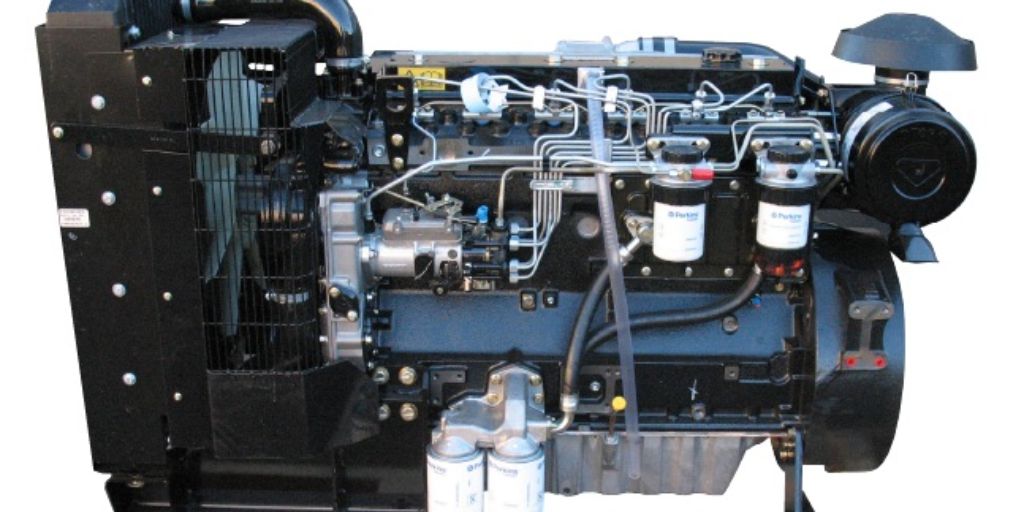

Founded in 1932 by Frank Perkins and Charles Chapman, Perkins Engines became synonymous with rugged diesel units for tractors, generators, and construction equipment.

By the 1950s, burgeoning postwar economies prioritized fuel economy, especially in Europe, where rationing memories lingered. Perkins seized the opportunity to market its compact, reliable diesels to carmakers.

The Perkins 4.99, a 1.6‑liter four‑cylinder diesel, was first adapted into the Morris Oxford and Austin Cambridge in the mid-1950s.

Producing around 40 horsepower but delivering ample torque at 1,500 rpm, the engine offered fuel economy improvements of up to 30% over equivalent petrol units.

Maintenance schedules remained simple: regular oil and filter changes, with no need for valves adjustments more frequent than every 10,000 miles — a schedule in line with farm use.

Later, the 4.108 (1.8 liter) and 4.203 (2.1 liter) units expanded applications. In the UK, the London taxi industry embraced them for their ability to idle all day without hiccups, run on marginal fuel quality, and survive hundreds of thousands of miles.

Overseas, Indian automaker Hindustan Motors licensed Perkins designs for the Ambassador sedan, producing a car almost unchanged from 1958 until 2014. Under bonnet simplicity, sturdy cast‑iron blocks, and mechanical fuel injection meant these cars became rolling testaments to tractor-engine resilience.

Despite modest performance — top speeds rarely exceeded 65 mph and acceleration from 0–50 mph could stretch beyond 20 seconds — the engines redefined expectations for diesel cars. By the late 1970s, Perkins diesels had powered over half a million European cars and countless industrial machines.

Their transition from the plow to the pavement showcased how a rugged workhorse design could democratize efficient motoring long before diesel’s rise in modern passenger cars.

Fordson-Derived Flathead – Tractor Lessons for the Hot Rod Revolution

Henry Ford’s American Agricultural Motors Company, launched in 1917 and later renamed Fordson, mass-produced tractors that helped motorize U.S. farms. Lessons learned in building millions of simple, affordable engines informed Ford’s first mass‑market V8 — the legendary Flathead.

Introduced in 1932, the Ford Flathead V8 was radically affordable at $385 and shared key design philosophies with Fordson tractors: cast‑iron blocks, sidevalve architecture, and an emphasis on low‑end torque.

While the Flathead was not a direct transplant of a tractor engine, many early enthusiasts swapped Fordson parts into their V8 builds — water pumps, carburetor mounts, and even crankshafts.

Post–World War II, surplus tractor components flooded the market, and hot rodders discovered that reinforced tractor crankshafts could handle higher revs when balanced.

Early drag racers and bootleggers exploited these parts for extra durability and ease of tuning. Workshops across Southern California, the birthplace of hot rodding, routinely interchanged gaskets and seal kits between tractor and automotive variants.

Throughout the 1930s and ’40s, the Flathead V8’s simplicity and parts availability made it the go-to motor for customizers. Cylinder head porting, manifold swaps, and supercharger kits proliferated, spawning a performance aftermarket still active today.

In this way, Ford’s agricultural heritage catalyzed a cultural revolution in automotive performance — the first grassroots tuning movement.

Decades later, nostalgia for the Flathead’s raw, mechanical charm has only grown. Vintage hot rods parade at car shows worldwide, their unmistakable V8 rumble echoing a time when farmyard reliability and street‑legal speed blended into something genuinely new.

International Harvester Engines – Bridging Farm and Field, Then Road

International Harvester (IH) pivoted from reaper machinery to tractors after World War I, becoming a global agricultural titan. In 1961, IH leveraged this expertise to launch the Scout — a precursor to the modern SUV.

The Scout’s inline-four engines, notably the 152 ci (2.5 L) and later the 196 ci (3.2 L), were derivatives of IH tractor powerplants, sharing cast‑iron blocks, crossflow head designs, and low‑idle torque curves ideal for off-road duties.

In Scout applications, these engines ran reliably on farm fuel mixes, tolerated overheating better than pure automotive motors, and could be rebuilt with simple instructions.

Ranchers and hunters appreciated that a Scout could serve as both pickup and utility vehicle, and under the hood lay an engine you could rebuild beside a creek if necessary.

Beyond the Scout, IH’s Travelall and medium-duty pickup trucks used similar engines, blurring lines between agricultural, commercial, and consumer vehicles.

While horsepower numbers were modest — often under 100 hp — torque figures around 170 lb‑ft at 1,800 rpm gave the machines genuine hauling capability.

Enthusiasts today revere IH engines for their mechanical straightforwardness. No electronic control units, just a mechanical fuel pump, distributor, and basic carburetor. Restoration guides for Scouts emphasize that parts interchangeability with tractor spares can rescue even the most neglected engine.

International Harvester’s foray into automotive engines demonstrated that, with suitable adaptations, a tractor design could underpin a versatile consumer vehicle.

The Scout’s enduring fan base owes much to this shared mechanical ancestry, proving that farm-tested durability found a ready home on family adventures.

Mercedes-Benz OM Diesel Engines – Tractor Roots in Taxi Legends

In the 1960s, Mercedes-Benz developed the OM600 series of diesel engines for tractors built by Lanz (acquired by Mercedes in 1956) and for industrial machinery.

These inline‑five and four-cylinder powerplants prioritized longevity over outright performance, featuring unit injectors, cast‑iron blocks, and single overhead camshafts.

Mercedes adapted these units for passenger cars: the OM615 (2.0 L), OM616 (2.4 L), and the later OM617 (3.0 L) turbocharged variant.

Installed in the W115, W114, and the legendary W123 series, these engines elevated diesels from economical but slow workhorses to respected highway performers.

The 300D Turbodiesel (OM617.951) delivered 125 hp and around 170 lb‑ft of torque — figures unheard of for passenger diesel in the 1970s.

Taxi fleets worldwide gravitated to these models for one simple reason: hardly any other engine could match their uptime.

Reports of 500,000-mile engines were commonplace, with basic maintenance—oil, filters, injector servicing—sufficient to keep them running like clockwork. Their tractor-derived strength meant even occasional overheating or poor-quality fuel rarely led to catastrophic failure.

Today’s diesel tuning community still prizes OM engines. Turbo upgrades, handcrafted camshafts, and performance exhaust kits boost output, but the core appeal remains: a bulletproof foundation that began its life pulling trailers across fields and ended up powering intercity cabs.

Fiat 500 Tractor Lineage – Small Farm Roots in a City Car Giant

Long before the Fiat 500 “Cinquecento” became an icon of Italian city life, Fiat was Europe’s largest tractor manufacturer through its Fiat Trattori division, founded in 1919.

Early Fiat engines — single‑ and twin‑cylinder units — emphasized compactness, ease of manufacture, and low‑end torque, traits essential for small farm work.

When Fiat set out to build an affordable car for postwar Italy, these same design goals applied. The 1957 Fiat 500 featured a 479 cc air‑cooled two-cylinder engine producing 13 hp.

While custom-built for the car, the 500’s powerplant leveraged Fiat Trattori experience in evicting heat from simple cast‑iron barrels and tolerating high under‑bonnet temperatures without elaborate cooling systems.

The engine’s simplicity extended to maintenance: accessible spark plugs, an easy‑to-remove cylinder barrel, and a basic carburetor. Farmers transitioning to urban dwellers found the familiarity comforting: mechanics trained on tractors could service the new city cars without retooling.

Over its 18‑year production, the Fiat 500’s engine grew to 594 cc and 17 hp, yet retained its core architecture. Its durability and ease of repair made it a staple in rural towns as much as in Rome’s tight streets.

Even today, Cinquecento restorations frequently rely on vintage tractor‑engine manuals for assembly guidance.

The Fiat 500 story exemplifies how agricultural engineering principles laid the groundwork for one of the most beloved small cars ever built — a machine whose lineage leads directly back to tractors that tilled Italian fields.

The journeys of these six engines—from their genesis in tractors and industrial machinery to their second lives under car bonnets—highlight an engineering truth: utility, durability, and simplicity can be as transformative in the automotive world as peak horsepower and top speed.

Ferruccio Lamborghini’s tractor insights birthed a supercar legend; Perkins democratized diesel motoring in Europe and India; Ford’s agricultural lessons fueled America’s hot‑rod culture; International Harvester proved farm engines could power SUVs; Mercedes-Benz built immortal taxi diesels from Lanz tractor roots; and Fiat parlayed tractor know‑how into a city‑car phenomenon.

In every case, the essential qualities that make tractors invaluable in agriculture — low‑end torque, robust construction, and serviceability without specialized tooling — proved equally advantageous for road vehicles.

The resulting cars and performance machines carried forward an ethos of engineering for longevity, repairability, and practical power delivery.

As the automotive industry hurtles toward electrification and software-defined vehicles, these stories serve as a reminder that mechanical simplicity can yield profound innovation.

Tractor engines may no longer drift into car showrooms unannounced, but their legacy persists in every durable diesel, every low‑end grunt of an off‑roader, and every enthusiast who cherishes an engine that “just keeps going.”

From pulling plows to carving corners, these powerplants underscore that greatness often springs from the unlikeliest of origins.

Also Read: The ‘Unkillable’ Engine That Was Once Used in Both Planes and Cars