When most people hear “Hemi,” their minds immediately jump to Chrysler, muscle cars, and iconic drag-strip legends.

But the hemispherical combustion chamber, a design that allows for larger valves, better airflow, and serious power, has a rich history far beyond the Mopar badge.

From hand-built British V8s to lightweight Italian marvels and Japanese precision engines, some of the most remarkable Hemi-powered machines were crafted without a single connection to Detroit.

In this article, we explore 8 of the best non-Chrysler Hemi engines, powerplants that pushed the boundaries of performance, engineering, and innovation in ways both subtle and spectacular.

These engines aren’t just curiosities for gearheads; they represent decades of automotive ingenuity, proving that the Hemi concept is as versatile and inspiring as it is powerful.

Whether you’re a vintage car enthusiast, a performance junkie, or simply curious about automotive history, these Hemi engines tell stories that go well beyond the muscle car era.

Aston Martin “Tadek Marek” V8 (1969–2000)

Lift the hood on a DBS V8 or a V8 Vantage, and the engine looks like it could belong in a gentleman’s Can-Am racer. Aston Martin’s first production V8 debuted in 1969, designed by Tadek Marek to replace the aging straight-six.

Right from the start, the 5.3-liter unit in the DBS V8 delivered more than 300 hp in standard street trim, a remarkable feat for a heavy GT riding on narrow 1960s tires.

Supercharged variants introduced in the 1990s pushed output to 550–600 hp, as seen in the rare Vantage V550 and V600 trims.

Over a span of more than three decades, this engine powered everything from relaxed automatic cruisers to aggressive Vantages designed to roast their rear tires with gusto.

The technical setup reads like a wish list for any hemi enthusiast. It’s an all-alloy V8 with four overhead cams, two per cylinder bank, feeding large valves in hemispherical chambers.

This design provides excellent airflow, generating substantial power even when tuned for emissions compliance, and it reacts positively to increased cam duration and compression.

In its wildest road-going form, the supercharged Vantage Le Mans V600 produced roughly 600 hp while still carrying four passengers with luggage. Chrysler’s 1970s experiments were bold, but a hand-built British quad-cam hemi GT capable of drafting airliners.

The Oldsmobile Rocket 88 is widely recognized as the starting point of the muscle car era, while the Pontiac GTO cemented the category in the minds of the American public.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Touring Superleggera was tasked by Aston Martin in 1966 with designing the long-overdue successor to the DB6.

Initially intended to feature a thumpin’ great V8 with a DOHC valvetrain, the DBS ultimately launched on September 25th, 1967, to critical acclaim, but with the DB6’s straight-six engine under the hood.

Designed by legendary engineer Tadeusz “Tadek” Marek, this six-cylinder unit failed to deliver the punch expected of a flagship Aston Martin.

The V8 wasn’t ready in time for the start of production, but by 1969, Aston Martin introduced the all-aluminum, double overhead cam V8 in the DBS V8.

This flagship model is often regarded as a British-flavored answer to the Ford Mustang, a comparison that makes sense when examining its rear quarters, striking side profile, and imposing road presence.

While a significant departure from previous Aston Martins, the DBS V8 wasn’t a muscle car in the traditional sense. The 5.3-liter V8 featured 16 more valves than a typical GM big-block V8, but the LS6 in the ultra-collectible 1970 Chevelle SS 454 was far more powerful and torquier.

Unlike Chevrolet, which built cars for dominance on the strip, Aston Martin followed its own path, redefining its lineup with bold styling and introducing the company’s first V8. Notably, the DBS V8 also held the title of fastest four-seat production car in the world.

The DBS V8 received a stronger manual transmission than its six-cylinder predecessor, GR70VR15 Pirelli Cinturato tires, and upgraded brake discs. Only 402 examples were produced. By 1972, the DBS V8 nameplate was simplified to just V8.

The facelifted Series 2 model adopted Bosch fuel injection, a mesh grille, twin headlights, and for the first 34 of 288 cars produced at Newport Pagnell, retained DBS V8 badging.

In 1973, Aston Martin reverted to carburetors with the Series 3, a seemingly odd decision that made sense in context. The Bosch fuel injection system couldn’t be made reliable, preventing compliance with stricter California emissions standards.

Twin-choke carburetors, however, defined the iconic styling cue of the Series 3: the pronounced hood scoop. With 310 horsepower and a 0–60 mph time of 5.7 seconds (manual transmission), this model lasted until October 1978, with 967 units produced.

Subsequent emissions regulations reduced the 5.3-liter engine to 288 horsepower in 1976, before Aston Martin introduced the 305-horsepower Stage 1 option in 1977, featuring new exhausts and camshafts.

The Series 4, or Oscar India specification, replaced the scoop with a power bulge, while the Series 5 sported a flatter hood thanks to the smooth and reliable Weber Marelli electronic sequential fuel injection.

Debuting in 1977 and continuing until 1989, the V8 Vantage earned the affectionate title of Britain’s first supercar, capable of 170 mph (270 km/h). Slightly faster to 60 mph than the Ferrari 365 GTB/4 Daytona, the high-performance V8 Vantage ended its run with the X-Pack option, producing over 400 horsepower.

In 1989, the Virage replaced the V8, while the final V8 Zagato was completed in 1990, closing the original V8 lineage.

Designed by chief stylist Giuseppe Mittino, this coachbuilt special edition honored the 1960s DB4 GT Zagato, with just 89 units produced, 52 coupes featuring Zagato’s signature double-bubble roof and 37 convertibles.

Regardless of year or specification, the Aston Martin V8 remains a highly desirable collectible, its combination of power and elegance guaranteed to turn heads wherever it goes.

Daimler Edward Turner V8 (1959–1969)

Before Jaguar absorbed the British Daimler company, Daimler produced its own distinctive and innovative engines, including this remarkable V8.

Edward Turner, who came from the motorcycle world and had already used hemi chambers in Triumph twins, adapted the concept to create 2.5- and 4.5-liter V8s with iron blocks and alloy heads.

These engines initially powered the fiberglass-bodied SP250 sports car and later the Majestic Major limousines and saloons.

The Daimler V8 relies on pushrods and a single cam, but the hemispherical chambers feature opposed valves and cleanly designed ports. The 2.5-liter version produced roughly 140 hp, giving the lightweight SP250 brisk performance for the late 1950s.

Meanwhile, the 4.5-liter engine in the Majestic Major delivered around 220 hp and massive torque, easily propelling a large limousine to motorway speeds.

Jaguar valued the engine so highly that after taking over Daimler, it continued producing the 2.5-liter version, fitting it into Jaguar Mark 2-based sedans.

No Chrysler tooling or licensing, just a motorcycle engineer applying hemi principles to a distinctly British small-block.

Ford 427 SOHC “Cammer” (1964–1967)

If the Chrysler 426 Hemi is the prom king, Ford’s 427 SOHC “Cammer” is the mischievous classmate doing burnouts in the parking lot. Ford rushed the engine’s development in the mid-1960s as a high-powered option for NASCAR.

Starting with the FE 427 “side-oiler” block, they added single-overhead-cam heads with hemispherical combustion chambers. Its “Cammer” nickname comes from the enormous cams, each driven by a timing chain long enough to double as a jump rope.

On paper, the Cammer ticked every hemi box: cross-flow heads, massive valves in domed chambers, and airflow that thrilled race tuners.

Ford rated the crate engines at roughly 615 hp, but period dyno sheets and reports indicate race trim outputs closer to 650–700 hp.

NASCAR immediately banned the engine as a special-purpose unit before it could dominate, pushing the 427 SOHC into drag racing, where funny cars and rail dragsters embraced its rev-happy nature and potent midrange.

While Chrysler had its own battles with NASCAR, the Cammer’s engineering was pure Ford.

In the 1960s, Ford’s overhead-cam 427 V8, famously dubbed the Cammer, ascended into automotive legend. Here’s the story behind that story.

By 2014, overhead-cam, multi-valve engines had become the industry standard, with anything less regarded as archaic. But back in the 1960s American automotive landscape, pushrod V8s were the cutting edge.

Into this simpler, more innocent world stepped Ford’s 427 CID SOHC V8, soon earning the nickname Cammer. Even today, the engine carries a powerful mystique. Let’s take a closer look.

Ford had been struggling all month at Daytona against the new 426 Hemi engines from Dodge and Plymouth. In response, Ford officials petitioned NASCAR to approve their in-development overhead-cam V8.

However, as the Journal reports, NASCAR boss Bill France rejected the engine. France viewed overhead cams and similar technology as European exotica, hardly suited to his vision of straightforward, American-style Grand National stock car racing.

Despite France’s ban, Ford pressed on with development, hoping to sway the NASCAR chief. In May 1964, a ’64 Galaxie hardtop fitted with the Cammer V8 was displayed behind Gasoline Alley at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, giving the assembled press a chance to inspect it.

Another early Cammer photo shows the original spark plug placement. Ford engineers had meticulously designed a perfectly symmetrical hemispherical combustion chamber with an optimized spark plug location, only to discover the plugs didn’t care where they sat.

They were eventually moved to the top of the chamber for easier access. This engine was configured for NASCAR use: note the cowl induction airbox, single carburetor, and cast exhaust manifolds.

Despite the Cammer’s exotic reputation, the engine was essentially a two-valve, single-overhead-cam conversion of Ford’s existing 427 FE V8, and a quick, cost-effective one at that.

Internally, the Cammer was nicknamed the “90-day wonder,” a low-investment parallel project to Ford’s more expensive DOHC Indy engine, which was based on the small-block V8.

To save time and money, the heads were cast iron and the cam drive used a roller chain. The oiling system was modified, and the cylinder cases were strengthened to handle the greater horizontal inertia loads at higher rpm. These improvements were eventually adopted across all 427 CID engines.

While not a Ford SOHC V8, this early 331 CID Chrysler Hemi is shown to illustrate a key advantage of the SOHC design as seen by Ford engineers. By placing the camshafts atop the cylinder heads, pushrods could be eliminated, allowing for larger, straighter intake ports.

One feature of the Cammer that continues to intrigue enthusiasts is the timing chain, it stretched nearly seven feet.

While cheaper and faster to develop than a full gear drive, it was less effective and introduced challenges. Racers quickly learned that cam timing had to be staggered four to eight degrees between banks to compensate for chain slack.

Jaguar XK6 (1949–1992)

Every time you open the bonnet of an old Jaguar and see those polished cam covers, you’re looking at a non-Chrysler hemi.

The XK inline-six debuted shortly after World War II and remained in production into the early 1990s, powering everything from XK120 roadsters to E-Types, XJ6 sedans, and D-Types that won Le Mans multiple times. It helped define Jaguar’s reputation for refined, fast GTs.

The XK top end embodies classic performance engineering: twin overhead cams, two large valves per cylinder, and deeply hemispherical chambers that accommodate wide valves and generous porting.

This layout allows exceptional airflow, still exploited by tuners via hotter cams, bigger carbs or fuel injection, and higher compression.

While emissions regulations eventually revealed the hemi chamber’s limitations at low loads, the XK’s combination of smoothness, racing pedigree, and accessible power makes it one of the longest-lived non-Chrysler hemi designs used in road cars.

The Jaguar XK inline-six engine powered a wide array of vintage and post-modern Jaguars, racing machines, and even military vehicles from 1949 through 1992.

Long before the Jaguar E-Type cemented the brand’s reputation for producing some of the fastest, most exotic, and visually stunning sports cars in 1961, the XK inline-six was already recognized for its smooth operation, solid power output, and remarkable reliability.

Jaguar co-founder Sir William Lyons, however, wanted more than just performance, he wanted his engine to look as elegant under the hood as it performed on the road, rivaling the visual appeal of engines from Bugatti or Duesenberg.

The result was the XK inline six-cylinder engine, which debuted in the 1948 Jaguar XK 120. Featuring 3.4 liters of displacement, dual overhead camshafts, dual SU side-draft carburetors, and aluminum engine castings, the XK engine was as aesthetically pleasing as the car it powered.

Jaguar buyers have always expected a blend of space, pace, and grace, and the company’s first post-war engine certainly delivered on the “pace” front.

Producing 160 horsepower at 5,000 rpm and 195 lb-ft of torque at 2,500 rpm, the XK 120 could accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in roughly ten seconds, a respectable figure for a post-war sports car. The “120” designation, of course, referred to the car’s top speed of 120 mph.

Sir William Lyons and his talented team of engineers began developing the all-new XK engine during their fire-watching duties in World War II.

After the war, the company had a running four-cylinder prototype that contained many of the elements that would evolve into the XK engine: dual overhead camshafts, two valves per cylinder, hemispherical combustion chambers, and polished cam covers.

The XK inline-six’s design also incorporated two sets of three cylinders with slightly wider spacing in the middle, optimizing coolant flow.

Each cylinder contained a cast aluminum piston with dual compression rings, a single oil ring, and a full-floating wrist-pin design to reduce friction. The domed piston tops delivered an early 8.0:1 compression ratio in the initial XK 120 models.

The engine’s aesthetic appeal was further enhanced by shiny aluminum components, including a cast aluminum head, front timing cover, cam covers, and oil pan.

Using an aluminum head alone saved 70 pounds, though the cast-iron engine block and transmission casing meant the full powertrain still weighed around 700 pounds.

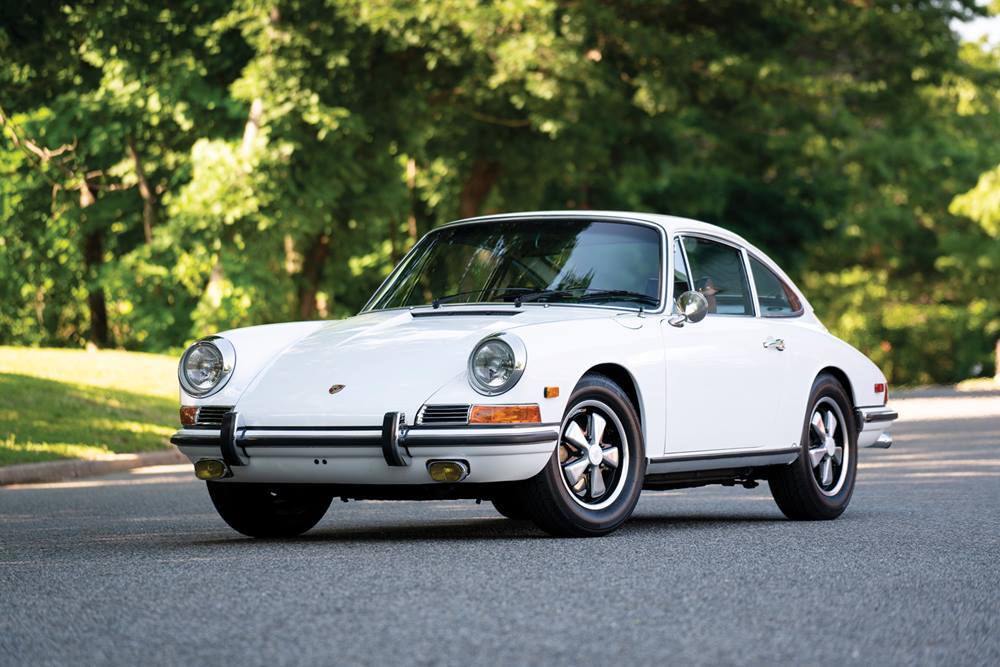

Porsche Air-Cooled Flat-Six (1963–1998)

Here is a stealthy hemi that almost no one calls a Hemi. The original air-cooled flat-six launched with the 1963 Porsche 911, using six individual heads, each with its own fully machined hemispherical chamber atop the air-cooled cylinder barrels.

Early 2.0-liter units made around 110 hp in street trim, but the design evolved into everything from 911S screamers to turbocharged and endurance-racing monsters.

Porsche maintained hemi chambers in most air-cooled 911 engines up to the 993 generation in 1998, refining port shapes and valvetrain layouts while keeping the fundamental dome-and-opposed-valves design.

The boxer configuration lowers the engine’s center of gravity, and the hemi heads ensure sufficient breathing for everything from mild 2.7-liter CIS engines to 450-hp twin-turbo 993 Turbos.

Here, the hemispherical head is a functional design element, not a marketing gimmick, making it very different from Chrysler’s approach but just as legitimate.

The 996-generation 911, notable for its “fried-egg” headlights, marked Porsche’s transition to water-cooled engines and debuted in 1999 with the naturally aspirated 300-hp 3.4L M96 engine.

While groundbreaking, the M96 quickly developed a reputation for patchy reliability. Meanwhile, the 986 Porsche Boxster reintroduced the mid-engine roadster to Porsche’s lineup, equipped with a smaller 201-hp 2.5L flat-six.

Over time, the M96 family expanded to include 2.7L, 3.2L, and 3.6L variants, offered in both naturally aspirated and turbocharged forms.

The M96 eventually evolved into the M97, before being replaced by the MA1 engine. Along the way, these engines gained more power and modern features, including direct injection, extending into the 991 generation, with several variants exceeding 500 hp.

The current range of flat-six engines, found in the 992-generation Porsche 911s, is highly refined and features twin-turbocharging, with a 7,500 rpm limit, a high figure for a turbocharged engine.

For naturally aspirated enthusiasts, the 4.0L flat-six in the 718 GT4 and 992 GT3 models revs to 9,000 rpm and produces over 500 hp.

At the top of the performance ladder, the 911 Turbo S with its twin-turbo 3.7L flat-six has reached a peak output of 640 hp in the latest models, demonstrating the flat-six’s incredible evolution from its early days.

Tatra T77 Air-Cooled V8 (1934–1938)

Long before “Hemi” became a muscle car badge, Czechoslovakia’s Tatra produced a luxury streamliner with a hidden hemi V8.

The T77 and T77A featured a rear-mounted, air-cooled 3.0–3.4-liter V8 with a magnesium crankcase and hemispherical combustion chambers.

The car itself looked like science fiction, complete with a central tail fin and aerodynamically tuned bodywork, and could cruise near 90 mph in the mid-1930s.

The engine was equally unconventional. Rather than using pushrods, a central camshaft between the cylinder banks operated large drilled rocker arms that actuated the valves in the hemi heads, reducing reciprocating mass and keeping packaging tidy.

Tatra prioritized low drag, manageable weight, and effective cooling for extended high-speed travel, and the hemi chambers fit perfectly. For anyone disputing Chrysler’s “we invented the Hemi” claim, mentioning “Tatra 77 did it in 1934” usually ends the debate.

Toyota V-Series “Toyota Hemi” V8 (1963–1997)

Toyota quietly developed its own Hemi V8 for more than thirty years, largely unknown outside Japan. The V-series V8 began in the early 1960s as Toyota prepared an upscale sedan to compete with American imports.

Yamaha assisted in designing the all-aluminum 2.6-liter engine, which debuted in the 1963 Crown Eight and later expanded to 3.0, 3.4, and 4.0-liter versions, almost exclusively in the Toyota Century, the company’s chauffeur-driven flagship.

Nicknamed the “Toyota Hemi” for its design, the V-series uses OHV two-valve heads with approximately hemispherical chambers and centrally positioned spark plugs.

This configuration, combined with all-aluminum construction, makes it compact, smooth, and relatively light for a V8 of the early 1960s.

Power peaked around 190 hp in the later 5V-EU 4.0-liter version, but in quiet luxury sedans, the engine’s creamy torque mattered far more than raw numbers.

Alfa Romeo Busso V6 (1979–2005)

Ask any Italian to name the best-sounding engine ever, and the Busso V6 is likely to come up. Alfa’s 60-degree “Busso” V6, named after designer Giuseppe Busso, emerged in 1979 when most manufacturers were abandoning thirsty performance engines.

It initially used six individual carburetors on the Alfa 6 sedan, producing a soundtrack that left every other car in traffic sounding lifeless.

Over time, the engine powered transaxle models like the GTV6 and 75/Milano, and eventually front-drive cars like the 164 and 156/147 GTA, where intake runners became chrome trumpet art.

Beneath the artistry, the Busso is genuine hemi hardware. Early single-overhead-cam heads used two valves per cylinder and hemispherical chambers that allowed nearly straight exhaust ports, enhancing flow and producing a sharp exhaust note.

Later 24-valve DOHC variants retained the chamber philosophy, increased displacement to 3.2 liters, and achieved up to 247 hp in the 156 GTA.

While it doesn’t generate the torque of a large American Hemi, it thrives at high rpm, responds beautifully to throttle inputs, and proves you don’t need eight cylinders to create a legendary Hemi-headed engine.