The boundary between race cars and road cars has always been a fascinating frontier in automotive engineering.

While pure racing machines are built with a singular focus on performance, a special breed of vehicles exists that bridges both worlds: street-legal cars with racing DNA.

These remarkable machines bring track-worthy performance to public roads, often developed through motorsport programs before being adapted for civilian use.

They represent the pinnacle of what’s possible when engineers are given the freedom to push boundaries while still meeting road regulations.

From homologation specials built to satisfy racing series requirements to technological showcases that transfer racing innovations to production vehicles, these cars embody the thrill of motorsport in a package you can drive to the grocery store.

The 12 vehicles profiled here span decades of automotive history and represent various approaches to the race car for the road concept.

Each carries the soul of competition while wearing license plates, offering enthusiasts the chance to experience something close to racing performance in a street-legal package.

1. Ferrari F40

The Ferrari F40 represents the raw essence of a race car adapted for road use, created as Enzo Ferrari’s final personally approved supercar before his death.

Developed from the 288 GTO Evoluzione racing project, this iconic machine debuted in 1987 with a singular purpose: delivering uncompromising performance without luxury distractions.

Its lightweight construction pioneered the use of carbon fiber, Kevlar, and aluminum, resulting in a curb weight of just 2,425 pounds revolutionary for its time.

Under the vented rear hood lurks a 2.9-liter twin-turbocharged V8 producing 478 horsepower, enabling a 0-60 mph sprint in just 3.8 seconds and a top speed of 201 mph making it the first production car to break the 200 mph barrier.

The racing influence pervades every aspect of the F40’s design, from its spartan interior featuring racing bucket seats and lack of carpeting to its aerodynamically optimized body with its massive rear wing.

What makes the F40 particularly special is its analog driving experience. With no power steering, no antilock brakes, no traction control, and a gated manual shifter, it demands total driver involvement.

The turbocharged engine’s notorious lag followed by explosive power delivery creates a driving experience that’s both challenging and thrilling.

Though never officially raced by Ferrari itself, the F40 did find success in competition when modified by private teams into the F40 LM and F40 Competizione variants, proving its racing pedigree.

The road car itself was essentially a homologation special that Ferrari produced in greater numbers than initially planned due to overwhelming demand.

Today, the F40 stands as perhaps the purest distillation of Ferrari’s racing heritage in road-legal form a vehicle that made no concessions to comfort or convenience in its pursuit of performance.

Its influence continues to resonate through automotive design and engineering, representing a high-water mark in the translation of race technology to the street.

2. Porsche 911 GT3 RS

The Porsche 911 GT3 RS stands as perhaps the most direct connection between contemporary motorsport and road-legal production cars available today.

Born from Porsche’s extensive racing program, particularly its GT3 class competition experience, the GT3 RS represents the pinnacle of the 911 platform’s track capabilities while maintaining full street legality.

The RS designation standing for “Rennsport” or “racing sport” in German has historically denoted Porsche’s most track-focused variants, and the modern GT3 RS lives up to this heritage.

What sets this machine apart is Porsche’s approach to development, where the road car and race car are developed in parallel, with technology and learnings flowing bidirectionally between the GT3 RS road car and the GT3 Cup and RSR racing programs.

Aerodynamics define the GT3 RS’s identity, with the current 992-generation model featuring the most aggressive aero package ever fitted to a production 911.

Its massive rear wing, front splitter, underbody aero elements, and roof-mounted air intake are all directly influenced by race car design, generating over 860 pounds of downforce at 177 mph more than double its predecessor.

Power comes from a naturally aspirated flat-six engine a motorsport-derived powerplant that revs to a stratospheric 9,000 RPM, producing around 518 horsepower without turbocharging in the current model.

The suspension system features racing-inspired components including ball joints throughout, adjustable settings, and helper springs.

Unlike many road-going track specials, the GT3 RS receives continuous updates derived directly from Porsche’s racing programs.

Technologies like the PDK dual-clutch transmission, rear-wheel steering, and advanced aerodynamics all represent racing innovations adapted for street use.

The car’s lightweight construction incorporates carbon fiber reinforced plastic for the hood, roof, doors, and aerodynamic elements.

What truly distinguishes the GT3 RS is its developmental history these are not merely road cars made faster, but purpose-built racing machines that have been adapted for road use.

Porsche’s engineering team includes the same personnel who develop their racing cars, ensuring authentic racing DNA throughout the vehicle.

3. McLaren F1

The McLaren F1 stands as perhaps the most legendary road car with racing DNA ever created. Conceived by renowned Formula 1 designer Gordon Murray, the F1 was initially envisioned purely as the ultimate road car, but its competition success would later cement its place in motorsport history.

Developed between 1989 and 1992, the F1 incorporated Formula 1 technology and thinking throughout its design, from its central driving position to its carbon fiber monocoque chassis the first in a production road car.

What makes the F1 extraordinary is how directly racing principles influenced its creation, despite not initially being intended for competition.

Murray’s obsession with weight reduction saw the use of gold foil as engine bay heat shielding, titanium components, and magnesium wheels.

The naturally aspirated 6.1-liter BMW V12 engine, producing 618 horsepower, was positioned with perfect weight distribution in mind and featured a Formula 1-inspired dry-sump lubrication system.

When McLaren reluctantly developed a racing version at customer request, the resulting F1 GTR dominated the 1995 24 Hours of Le Mans, taking first, third, fourth, fifth, and thirteenth places an unprecedented achievement for a production-based car in its first attempt.

This competition success led to the creation of the F1 LM road car, essentially a street-legal version of the Le Mans winner, and later the F1 GT “Longtail” homologation special.

The F1’s driving experience remains singular even today. The central driving position provides perfect visibility and balance, while the manual transmission and naturally aspirated engine deliver unfiltered feedback.

With no electronic driving aids beyond ABS, the F1 demands complete driver attention and skill hallmarks of a true racing machine.

Perhaps most tellingly, the F1’s 240+ mph top speed remained unbeaten for over a decade, and its naturally aspirated production car speed record stood until 2005.

Murray’s insistence on applying Formula 1 design principles to a road car created a vehicle so advanced that many of its innovations are only now becoming common in hypercars, nearly three decades after its introduction.

4. Ford GT

The Ford GT represents a rare example of a production car born directly from a manufacturer’s desire to dominate at the highest level of endurance racing.

While the original GT40 of the 1960s was a purpose-built race car later adapted for road use, the modern Ford GT took a different approach developing both road and race versions simultaneously as part of a coordinated program to win at Le Mans on the 50th anniversary of Ford’s legendary 1966 victory.

The second-generation Ford GT, introduced in 2016, broke with supercar conventions by utilizing a 3.5-liter twin-turbocharged EcoBoost V6 rather than a traditional V8.

This decision wasn’t made for the road car and then adapted for racing it was specifically chosen because Ford wanted an engine platform that could succeed both on track and on the street.

The racing program directly influenced every aspect of the car’s design, from its teardrop-shaped cabin to its distinctive flying buttresses, which create aerodynamic channels in the rear wing.

What truly sets the Ford GT apart is how its development prioritized racing success. The road car team had to work within constraints set by the racing program, rather than vice versa.

The unusual mid-mounted port fuel injection location, the compact cockpit dimensions, and the push-rod suspension all existed to make the race car competitive while still being adaptable for the street version.

This approach paid dividends when the Ford GT race car won its class at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 2016 – exactly 50 years after Ford’s first victory beating Ferrari once again.

The road car’s 647 horsepower, carbon fiber construction, and advanced aerodynamics, including an active rear wing and movable flaps in the front splitter, all derived directly from the race program.

Ford’s strict application process for purchasing the GT further emphasized its racing heritage – potential owners needed to demonstrate they would drive the car rather than store it, and many successful applicants had racing experience.

Select owners even received special Heritage Edition models commemorating historic Ford racing liveries.

The Ford GT stands as a testament to how a modern manufacturer can successfully develop a racing program and road car in tandem, creating a street-legal vehicle with genuine competition DNA.

Also Read: 10 V8 Engines That Are Known for Their Exceptional Longevity

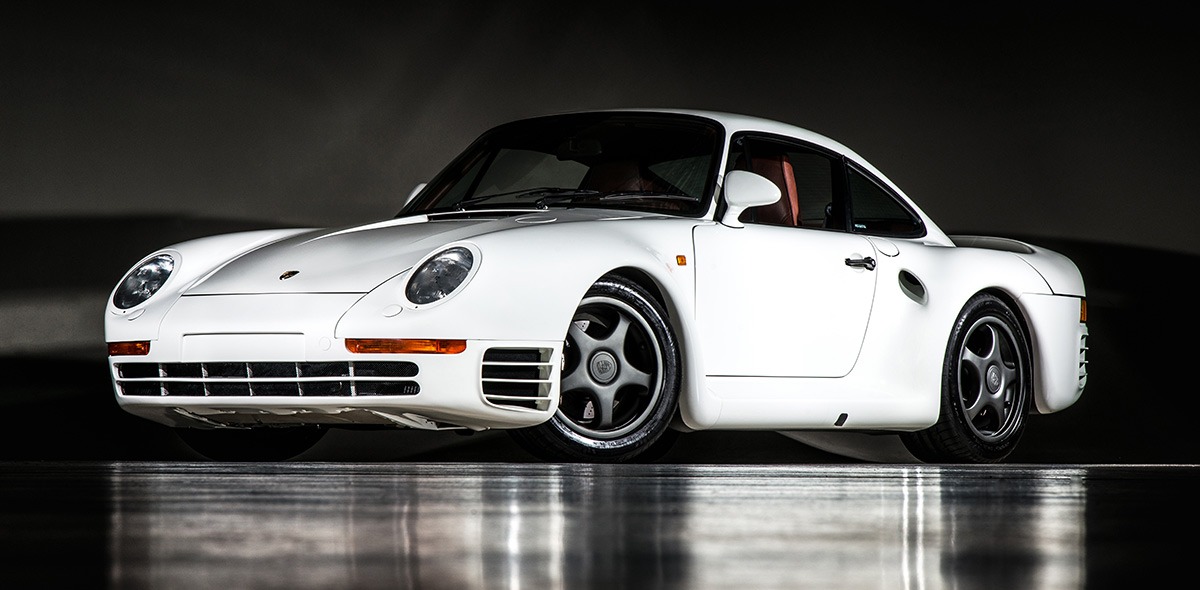

5. Porsche 959

The Porsche 959 represents one of the most significant technological leaps in the evolution of street-legal race cars.

Developed initially for Group B rally racing in the early 1980s, the 959 became the template for the modern supercar, introducing technologies that would take decades to become mainstream in production vehicles.

Porsche’s approach was revolutionary creating a rolling laboratory that could dominate in competition while advancing road car technology.

The 959’s racing DNA is evident in its sophisticated all-wheel-drive system, which featured variable torque distribution that could be adjusted based on conditions technology derived directly from Porsche’s rallying ambitions.

Though Group B was canceled before the 959 could fully compete in the championship, modified racing versions did prove successful, most notably winning the grueling Paris-Dakar Rally in 1986.

What truly set the 959 apart was its comprehensive integration of racing technology. Its twin-turbocharged flat-six engine featured sequential turbochargers to eliminate lag, producing 444 horsepower astronomical for 1986.

The body utilized Kevlar composite panels over an aluminum chassis to save weight while maintaining strength.

Its complex suspension system could adjust ride height automatically at speed, while magnesium wheels with hollow spokes reduced unsprung weight.

The technological showcase continued with run-flat tires that incorporated pressure sensors – the first production car to feature such a system.

Its aerodynamic profile, developed through extensive wind tunnel testing, achieved zero lift at high speeds without the need for visible wings or spoilers.

While only 337 production examples were built, the 959’s influence extended far beyond its limited numbers.

Its Porsche-Steuer Kupplung (PSK) all-wheel-drive system became the foundation for the all-wheel-drive systems in future 911 models.

The sequential turbocharging concept influenced engine development across the industry, and its use of exotic materials became a template for supercar construction.

The 959 exemplifies how racing development can transform road car technology. Originally too advanced to be imported to the United States due to crash testing requirements, it eventually received collector vehicle exemption status, allowing these technological marvels to be enjoyed on American roads a true race car for the street that changed automotive history.

6. Dodge Viper ACR

The Dodge Viper ACR (American Club Racer) represents the American approach to creating a track-focused street-legal machine raw, unapologetic, and pushes street legality to its absolute limits.

While the standard Viper was already an exercise in excess, the ACR variant transformed it into what many consider the most track-capable production car ever to wear a license plate.

What distinguishes the Viper ACR, particularly in its final fifth-generation form, is its unwavering focus on mechanical grip and aerodynamic downforce rather than electronic driving aids.

The Extreme Aero package generated over 2,000 pounds of downforce at top speed more than any production car of its era.

This remarkable downforce came from a massive adjustable dual-element rear wing, removable front splitter extension, and dive planes that wouldn’t look out of place on a dedicated racing car.

The ACR’s racing credentials were proven repeatedly on tracks worldwide. Between 2015 and 2017, it set 13 production car lap records at circuits including Laguna Seca, Road Atlanta, and Virginia International Raceway.

These records weren’t set by factory racing drivers but by the Viper’s development engineers a testament to its accessible performance envelope despite its fearsome reputation.

Under the massive hood sat a naturally aspirated 8.4-liter V10 producing 645 horsepower, connected to a six-speed manual transmission no automatic option was ever offered for the ACR.

This powertrain configuration maintained the analog, driver-focused experience increasingly rare in modern performance cars.

The ACR’s suspension system featured 10-way adjustable, remote-reservoir Bilstein coilovers with three inches of height adjustability, allowing owners to optimize the setup for specific tracks.

Carbon ceramic brakes specially developed Kumho tires, and five-way adjustable stability control gave drivers tools to extract maximum performance.

What made the Viper ACR special among track-focused road cars was its lack of compromise it sacrificed everyday comfort and driveability to push the boundaries of what was possible in a street-legal package.

With minimal sound insulation, an interior focused solely on driving, and suspension tuning that prioritized lap times override quality, the ACR demanded commitment from its owners.

When production ended in 2017, the Viper ACR represented the culmination of the American front-engine, rear-drive supercar formula a race car for the road that chose mechanical solutions over electronic complexity.

7. BMW M3 GTR

The BMW M3 GTR stands as one of the most fascinating examples of a homologation special road car built specifically to satisfy racing regulations.

Unlike most cars on this list, which began as road cars before receiving racing technology, the M3 GTR road car was created after the race car, solely to legitimize BMW’s American Le Mans Series (ALMS) competitor.

The story begins in 2001 when BMW Motorsport created the M3 GTR race car to compete in the GT class of the ALMS.

Instead of using a modified version of the standard M3’s straight-six engine, BMW developed a purpose-built 4.0-liter P60 V8 producing approximately 450 horsepower.

This gave the race car a significant advantage, helping it dominate the 2001 season. Competitors, particularly Porsche, protested that the V8-powered M3 violated the spirit of production-based racing, as no such engine was available in the road-going M3.

The ALMS responded by changing the rules for 2002, requiring manufacturers to produce at least 10 road-legal versions of their race cars and sell at least 100 engines identical to those used in competition.

BMW’s response was the road-legal M3 GTR a vehicle never intended for public consumption but built to satisfy regulatory requirements.

Only six examples were reportedly completed (some sources say 10), priced at an astronomical €250,000 (approximately $400,000 in 2021 dollars) to discourage public purchases.

The road car featured a detuned version of the race engine producing 380 horsepower, connected to a six-speed manual transmission.

The street version retained much of the race car’s character, with carbon fiber-reinforced plastic body panels, an aggressively vented hood, a prominent rear wing, and a roll cage.

The interior featured racing bucket seats, reduced sound insulation, and a minimalist approach to luxury.

Ultimately, BMW withdrew from the ALMS after rule changes made the M3 GTR uncompetitive, and the road cars were reportedly retained by BMW rather than sold to the public.

The M3 GTR’s legacy lives on as a prime example of a manufacturer creating a road-legal vehicle specifically to homologate a racing program, rather than the more common approach of adapting an existing production car for competition.

The M3 GTR later gained cultural significance through its appearance in the Need for Speed video game series, introducing this rare homologation special to millions who would never see one in person.

8. Aston Martin Valkyrie

The Aston Martin Valkyrie represents perhaps the most direct transfer of modern Formula 1 technology to a street-legal vehicle ever attempted.

Conceived through a partnership between Aston Martin and Red Bull Racing, with legendary F1 designer Adrian Newey leading the aerodynamic development, the Valkyrie blurs the line between road car and racing machine to a degree previously thought impossible.

The Valkyrie’s most striking feature is its aerodynamic philosophy, which borrows directly from Formula 1.

Massive Venturi tunnels run underneath the car, generating tremendous downforce without requiring the large wings typical of hypercars.

The cockpit’s teardrop shape maximizes airflow while minimizing frontal area, and the suspension components are mounted directly to the carbon fiber monocoque to allow clean air channels throughout the vehicle.

At the heart of the Valkyrie sits a naturally aspirated 6.5-liter Cosworth V12 engine capable of revving to an astounding 11,100 rpm territory previously reserved for racing engines.

This powerplant produces 1,000 horsepower without turbocharging or supercharging, with an additional 160 horsepower provided by a hybrid system developed with Formula 1 KERS technology expertise from Rimac and Integral Powertrain.

The Valkyrie’s Formula 1 influence extends to its weight-saving measures. The carbon fiber tub weighs just 165 pounds, the titanium exhaust system weighs less than 14 pounds, and even the Aston Martin badge on the nose is a chemical-etched aluminum piece just 70 microns thick 30 percent thinner than human hair.

The result is a dry weight of just 2,227 pounds. Inside, the F1 inspiration continues with a fixed seat molded into the carbon tub (the pedals and steering wheel adjust instead), a steering wheel resembling those found in Formula 1 cars, and a seating position similar to open-wheel racers with feet raised above hip level.

While still extraordinarily rare, with just 150 road cars planned, the Valkyrie’s existence proves that modern Formula 1 technology can be adapted for road use albeit at extreme cost and with compromises to everyday usability.

The car’s development also spawned the Valkyrie AMR Pro track-only variant and influenced Aston Martin’s Le Mans Hypercar program, demonstrating the bi-directional flow of technology between road cars and racing machines at the highest level of performance.

9. Lancia Stratos

The Lancia Stratos HF represents one of the purest examples of a purpose-built competition car adapted for road use.

Unlike many homologation specials that begin as production models before receiving modifications for racing, the Stratos was conceived from the outset as a rally weapon, with the road-going versions built solely to satisfy homologation requirements.

The Stratos originated from Lancia’s desire to replace the aging Fulvia rally car with something purpose-built for the World Rally Championship.

Designer Marcello Gandini at Bertone created the Stratos’s distinctive wedge shape with competition as the primary consideration.

The short wheelbase, mid-engine layout, and wide track were all optimized for rally stages rather than comfortable road use.

At the heart of the Stratos sat the 2.4-liter Ferrari Dino V6 engine, producing approximately 190 horsepower in road trim and up to 280 horsepower in Group 4 competition specification.

This Ferrari connection added exotic appeal to what was already a revolutionary design. The engine’s placement behind the driver, combined with the car’s minimal overhangs, created near-perfect weight distribution for handling the varied surfaces encountered in rallying.

What made the Stratos particularly special was how thoroughly its design prioritized competitive advantage.

The wraparound windshield provided exceptional visibility for spotting rally stage hazards. The short length made the car agile on tight mountain roads. Even the bodywork was designed for rapid removal entire front and rear sections could be quickly detached for service during rallies.

The Stratos dominated the World Rally Championship, winning titles in 1974, 1975, and 1976, and continued winning rallies until 1981 long after its official factory support had ended.

This competition’s success justified the car’s compromised road manners, which included challenging rearward visibility, a noisy cabin, and suspension tuned for gravel stages rather than highways.

Approximately 492 Stratos were built, with roughly 400 being road cars created purely to satisfy homologation requirements.

Today, the Stratos stands as perhaps the most successful purpose-built rally car ever adapted for road use a machine where every aspect of its design was influenced by competition needs rather than comfort or practicality.

The Stratos’s legacy is so significant that in 2018, a modern interpretation called the New Stratos was produced in limited numbers, maintaining the original’s competition-focused ethos while updating its performance capabilities.

10. Lexus LFA

The Lexus LFA represents a unique approach to creating a street-legal race car a vehicle conceived as a technological showcase that developed racing versions during its lengthy production development.

Unlike traditional homologation specials built to satisfy racing regulations, the LFA’s road and race versions evolved simultaneously over a decade-long gestation period, with learnings from each influencing the other.

What distinguishes the LFA is its bespoke 4.8-liter V10 engine, co-developed with Yamaha’s music division to create what many consider the most aurally fascinating engine note of any modern supercar.

This naturally aspirated powerplant revs to 9,000 RPM and responds so quickly that Lexus had to develop a digital tachometer because analog gauges couldn’t keep pace with the engine’s ability to gain 6,000 RPM in just 0.6 seconds.

The LFA’s racing DNA extends throughout its construction. The center monocoque utilized carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) developed through Toyota’s Formula 1 program, requiring such specialized manufacturing techniques that Lexus built a dedicated loom to weave the carbon fiber.

This technology transfer continued as Lexus campaigned racing versions of the LFA at the 24 Hours of Nürburgring during the car’s development, using the competition experience to refine the production model.

The culmination of this racing development was the LFA Nürburgring Package – a track-focused version featuring increased power, revised transmission mapping, and enhanced aerodynamics including a fixed carbon fiber wing.

This model set a production car lap record at the Nürburgring of 7:14.64 in 2011, demonstrating the effectiveness of its racing-derived technology.

Perhaps most telling about the LFA’s race car character is how it was manufactured and sold. Each of the 500 examples was hand-built by a team of Takumi master craftsmen at a rate of just one per day.

Lexus lost money on every car despite the $375,000 price tag, treating the project as a technology development exercise rather than a profit-generating product.

The LFA’s significance lies in how it represents a major manufacturer using a limited-production road car program as a development platform for racing technologies that would later influence its broader production lineup.

The carbon fiber expertise, electronic systems, and high-performance engine technologies pioneered in the LFA now appear throughout the Lexus and Toyota families, making it a true race car for the road with lasting impact.

11. Mercedes-Benz CLK GTR

The Mercedes-Benz CLK GTR stands as perhaps the most extreme example of a homologation special in modern automotive history.

Unlike most road-going race cars, which start as production vehicles before being modified for competition, the CLK GTR was conceived, designed, and built purely as a racing car for the FIA GT Championship, with the street versions created afterward solely to satisfy homologation requirements.

Mercedes-Benz’s AMG performance division was tasked with creating a car to compete in the 1997 FIA GT Championship, where rules required manufacturers to produce at least 25 road-legal versions of their race cars.

Working under incredible time pressure, AMG developed the CLK GTR race car in just 128 days from a blank sheet to a competitive vehicle.

The racing version bore almost no relationship to the production CLK coupe beyond some superficial styling cues and the name it was a purpose-built mid-engine race car with a carbon fiber monocoque chassis.

After the race car proved successful, winning the 1997 championship, Mercedes-Benz fulfilled its homologation obligation by producing 25 road-going versions (20 coupes and 5 roadsters).

These street-legal CLK GTRs retained almost everything from their racing counterparts, with minimal concessions to road use.

The 6.9-liter naturally aspirated V12 engine produced 604 horsepower, mounted to a sequential six-speed transmission in a carbon fiber chassis.

What makes the CLK GTR especially remarkable is how little was changed from race to road specification.

The interior, though featuring leather upholstery and air conditioning, maintained the racing car’s spartan approach with exposed carbon fiber, minimal sound deadening, and racing-style switchgear.

Ground clearance remained minimal, visibility was compromised by racing design priorities, and the sequential transmission offered no concessions to daily driveability.

At the time of its release in 1998, the CLK GTR was the most expensive production car, with a price tag of approximately $1.5 million.

Its extreme nature is evidenced by its performance specifications of 0-60 mph in 3.8 seconds and a top speed of 214 mph which were achieved through pure racing technology rather than luxury car refinement.

The CLK GTR exemplifies how homologation requirements can result in extraordinary road cars that would never exist otherwise vehicles that prioritize competition success above all else, making minimal concessions to practicality, comfort, or everyday usability in their transition from track to street.

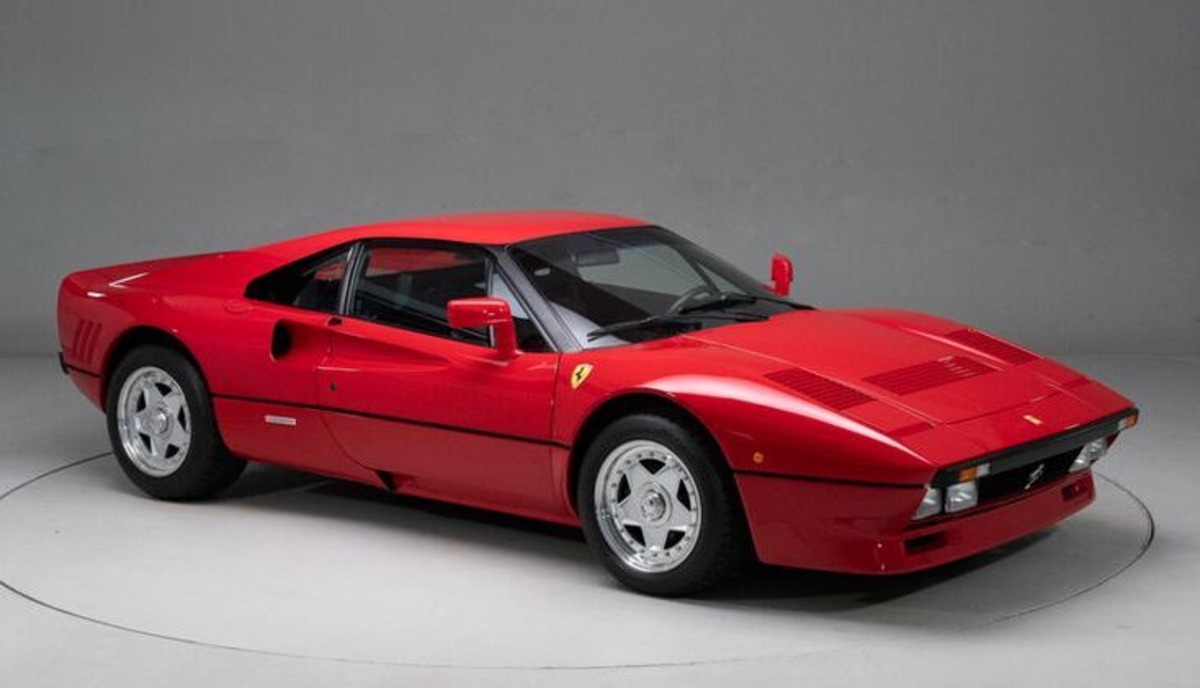

12. Ferrari 288 GTO

The Ferrari 288 GTO represents a fascinating chapter in the story of race cars adapted for the road, particularly because the competition series it was designed for never materialized.

Created as a homologation special for the Group B circuit racing series, the 288 GTO became the first in Ferrari’s line of limited-production supercars when Group B was canceled before the car could compete.

Developed from the Ferrari 308 GTB, the 288 GTO featured extensive modifications that transformed it into something far more extreme.

While it maintained a visual connection to the production 308, nearly every component was purpose-designed for high-performance competition.

The wheelbase was extended, the body was crafted from lightweight composite materials including kevlar and fiberglass, and the engine was completely reimagined.

The heart of the 288 GTO was its 2.9-liter twin-turbocharged V8, mounted longitudinally rather than transversely as in the 308, producing 400 horsepower an astonishing figure for 1984.

This powertrain configuration necessitated significant chassis modifications, and the resulting package was capable of 0-60 mph in approximately 4.9 seconds and a top speed of 189 mph, making it the fastest production car of its era.

What gives the 288 GTO its special place in racing-derived road cars is how thoroughly it was engineered for competition that never came.

The Group B circuit racing series was canceled following safety concerns in its rally counterpart, leaving the 288 GTO without its intended racing purpose.

Nevertheless, Ferrari completed the planned production run of 272 cars (exceeding the 200 required for homologation), all of which quickly sold despite a significant price premium over standard Ferrari models.

The 288 GTO’s racing DNA ultimately found expression in the 288 GTO Evoluzione five prototype vehicles that pushed the Group B concept even further with more power, lighter weight, and extreme aerodynamics.

These Evoluzione models would directly influence the development of the Ferrari F40, creating a lineage of race-bred Ferrari supercars that continues today.

As the first modern Ferrari supercar and the progenitor of the F40, F50, Enzo, and LaFerrari, the 288 GTO occupies a unique position in automotive history a competition car without a competition series that nevertheless changed the direction of Ferrari road car development and established the template for limited-production supercars with racing technology.

Also Read: 10 Diesel Engines That Last Forever and Are Built to Handle Extreme Conditions