The fusion of aerospace and automotive engineering has produced some of the most extraordinary vehicles ever built.

When jet engine technology migrates from the skies to the road, the result is a class of supercars that defies conventional automotive design principles.

These remarkable machines harness the raw power of jet propulsion systems utilizing turbines, aerodynamic principles, and materials developed for aircraft to achieve unprecedented performance.

From concept cars that never reached production to record-breaking speed demons, these vehicles represent the absolute pinnacle of automotive ambition.

They embody the relentless human pursuit of speed, challenging the very limits of what’s possible on four wheels.

While traditional supercars rely on pistons and crankshafts, these extraordinary machines employ compressors, combustion chambers, and exhaust nozzles more commonly found in aircraft, creating a driving experience unlike anything else on the road.

The following twelve vehicles showcase how jet engine technology has transformed automotive engineering, resulting in some of the most revolutionary and breathtaking supercars ever conceived.

1. Chrysler Turbine Car (1963)

The Chrysler Turbine Car stands as one of history’s most ambitious production experiments. Developed during the height of the Jet Age, this bronze-colored marvel represented Detroit’s first serious attempt at bringing gas turbine technology to consumer automobiles.

Chrysler’s engineers adapted aircraft turbine principles to create a powerplant that could run on virtually any combustible liquid including diesel, kerosene, vegetable oil, and even perfume.

The A-831 turbine engine generated 130 horsepower and an impressive 425 lb-ft of torque at stall speed, providing an immediate throttle response that conventional engines couldn’t match.

The car’s most distinctive characteristic was its unmistakable jet-like whine, earning it the nickname “The Flying Fish” among automotive enthusiasts.

Chrysler produced 55 units, distributing 50 to selected customers for a real-world testing program that lasted three years.

The turbine engine offered remarkable advantages: it contained roughly 80% fewer moving parts than conventional piston engines, required no antifreeze, was immune to cold-starting problems, and never needed warm-up time.

However, technological hurdles ultimately prevented mass production. The engine’s ceramic regenerator system suffered from thermal expansion issues at high temperatures, fuel economy was poor by contemporary standards, and the exhaust temperatures could exceed 500°F.

Additionally, emissions standards introduced in the late 1960s posed challenges that the turbine technology couldn’t easily overcome.

Despite never reaching mainstream production, the Chrysler Turbine Car represented a pivotal moment in automotive history demonstrating how jet-derived technology could fundamentally transform the driving experience.

Its legacy lives on through the nine surviving examples, most notably at the Smithsonian Institution and Walter P. Chrysler Museum, serving as a testament to American engineering ingenuity and the era’s limitless technological optimism.

2. Howmet TX (1968)

The Howmet TX (Turbine eXperimental) remains one of motorsport’s most audacious engineering experiments, distinguished as the only turbine-powered car to win sanctioned races in international competition.

Developed through a collaboration between racing driver Ray Heppenstall and Howmet Corporation, a manufacturer of gas turbine components for aircraft, this revolutionary race car utilized a Continental TS325-1 helicopter turbine engine producing 350 horsepower.

The powerplant weighed just 170 pounds less than half the weight of comparable piston engines creating an unprecedented power-to-weight ratio for its time.

Unlike conventional race cars, the Howmet TX produced its distinctive characteristics through turbine operation.

With virtually no lag between throttle input and power delivery, drivers experienced immediate torque across the entire rev range.

The turbine generated its spine-tingling wail at 57,000 RPM nearly ten times higher than typical racing engines.

The absence of a traditional gearbox further simplified the driving experience, providing seamless acceleration without shifting interruptions.

The TX made its competition debut in 1968, competing in both American and European events, including the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Its finest moments came at the SCCA races at Marlboro and Bridge Hampton where it achieved outright victories proving that turbine technology could indeed compete at the highest levels of motorsport.

The car’s aerodynamic profile, developed using aircraft principles, generated significant downforce while minimizing drag essential characteristics given the unique power delivery of the turbine.

Despite its groundbreaking achievements, the Howmet TX’s racing career was cut short when rule changes effectively banned turbine engines from competition.

Officials mandated restrictive air intake limitations that disproportionately affected turbine performance.

Though its competitive life lasted just one season, the Howmet TX demonstrated the extraordinary potential of jet engine technology in automotive applications.

Today, the surviving examples remain among the most sought-after experimental race cars, representing a fascinating convergence of aerospace and automotive engineering during a period of unprecedented technological experimentation.

3. Jaguar C-X75 (2010)

The Jaguar C-X75 represents one of the most technologically advanced and visually stunning applications of jet engine technology in supercar design.

Revealed at the 2010 Paris Motor Show to celebrate Jaguar’s 75th anniversary, this revolutionary concept employed four electric motors (one per wheel) producing a combined 778 horsepower, supplemented by two micro gas turbines that generated electricity rather than providing direct propulsion.

These miniaturized turbines, developed in partnership with Bladon Jets, spun at an astonishing 80,000 RPM, acting as range extenders for the electric powertrain.

What distinguished the C-X75’s implementation of jet technology was its innovative approach to energy conversion.

Rather than using turbines for thrust as in jet aircraft, Jaguar’s engineers harnessed them as electrical generators, solving many traditional challenges associated with turbine-powered cars.

The system produced minimal noise, reduced emissions significantly, and achieved an electric range of 68 miles extraordinary figures for 2010.

When the turbines activated, they extended the vehicle’s range to 560 miles while maintaining hypercar performance: 0-62 mph in 3.4 seconds and a top speed exceeding 205 mph.

The C-X75’s aerodynamic profile further reflected aerospace influence, with its carbon fiber construction and fluid lines achieving a remarkably low drag coefficient while generating substantial downforce.

The interior continued the aviation theme with a fighter jet-inspired cockpit featuring minimal switchgear and a digital display system showing turbine status and power flow.

In 2011, Jaguar announced a limited production run in partnership with Williams Advanced Engineering, replacing the micro-turbines with a highly-tuned conventional engine for practical production.

However, the global economic climate led to the project’s cancellation in 2012. Though never reaching customers’ garages in its purest form, the C-X75 gained cultural prominence when featured as a villain’s car in the James Bond film “Spectre.”

The concept remains one of automotive history’s most innovative expressions of jet engine technology, influencing hybrid hypercar development for years afterward and demonstrating how aerospace principles could revolutionize sustainable high-performance vehicles.

4. Thrust SSC (1997)

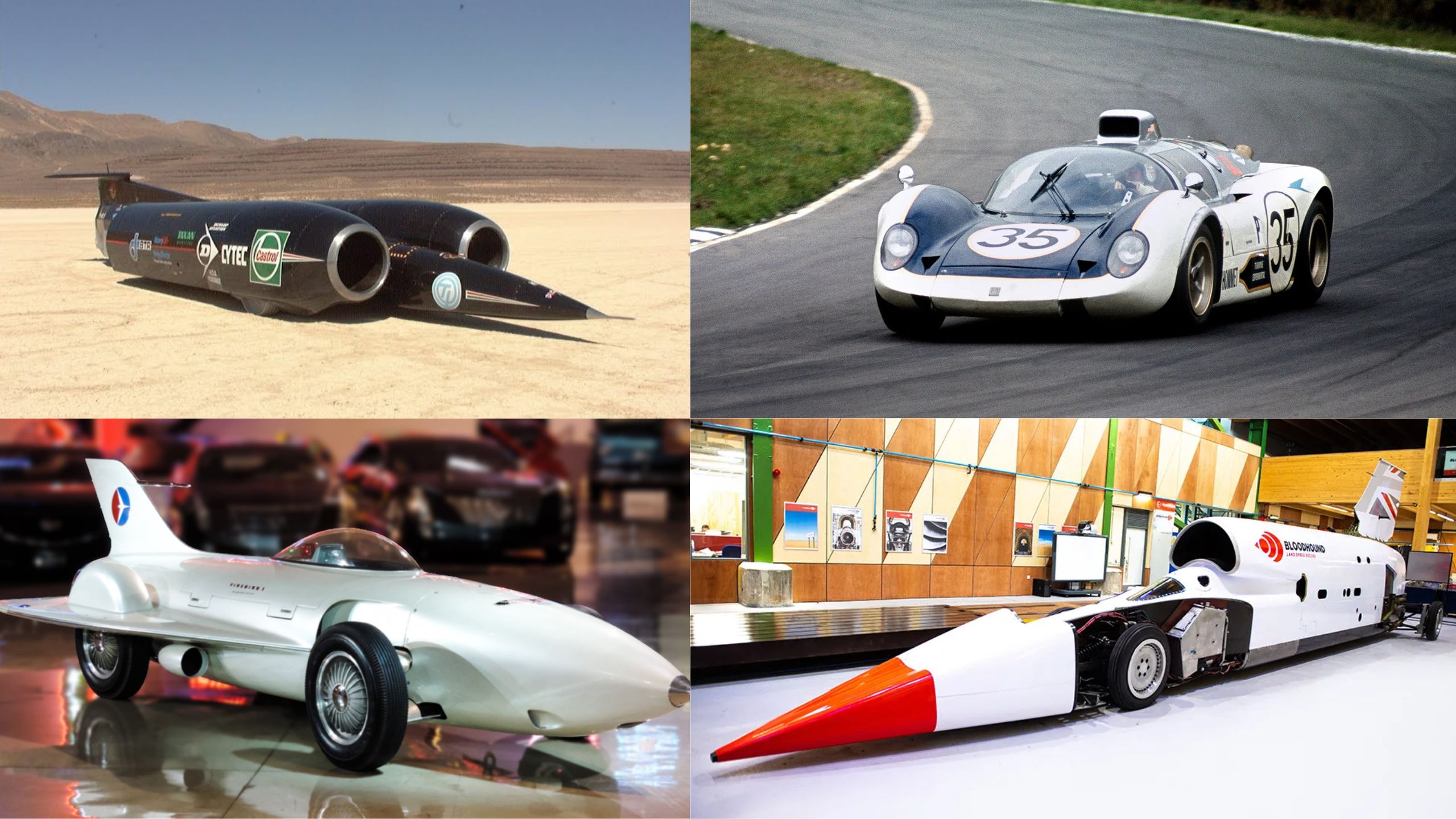

The Thrust SSC (SuperSonic Car) stands as humanity’s ultimate expression of jet engine technology applied to land vehicles.

This extraordinary machine holds the distinction of being the first and only car to officially break the sound barrier, setting the current World Land Speed Record of 763.035 mph (1,227.985 km/h) on October 15, 1997, in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert.

Unlike conventional supercars, the Thrust SSC employed pure jet propulsion through two massive Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan engines the same powerplants used in the F-4 Phantom II fighter jet generating a combined 110,000 horsepower.

The vehicle’s design represented a watershed moment in aerospace-automotive convergence. Led by Richard Noble and driven by RAF fighter pilot Andy Green, the engineering team faced unprecedented challenges in creating a land vehicle capable of supersonic speeds.

The 54-foot-long, 10.5-ton behemoth required revolutionary aerodynamic solutions to prevent lift at transonic velocities.

Computer modeling and wind tunnel testing led to its distinctive twin-hull configuration with engines mounted above the chassis, creating a carefully managed shockwave pattern that kept the vehicle grounded at speeds where conventional cars would become airborne.

The Thrust SSC’s immense power created extraordinary physical phenomena during its record runs.

The twin afterburning turbofans consumed over 4 gallons of fuel per second, generating shockwaves that triggered small earthquakes detectable five miles away.

The sonic boom produced when breaking the sound barrier confirmed the vehicle had exceeded Mach 1.

Driver Andy Green experienced up to 3G of acceleration and deceleration forces, requiring fighter pilot training to maintain consciousness and control.

While not road-legal by any definition, the Thrust SSC represents the absolute pinnacle of jet engine application for land transportation.

Its achievement stands unbroken after more than two decades, with subsequent challenges facing insurmountable financial and technical barriers.

The vehicle now resides in Coventry Transport Museum as a testament to human engineering ingenuity, demonstrating how jet propulsion technology can transcend the boundaries between aerospace and automotive domains to achieve what was once thought physically impossible a land vehicle faster than sound itself.

Also Read: 10 Street-Legal Cars That Feel Like Formula 1 Machines

5. Turbonique Drag Axle (1960s)

The Turbonique Drag Axle represents perhaps the most radical application of jet engine technology ever made commercially available to automotive enthusiasts.

Developed in the 1960s by aerospace engineer Gene Middlebrooks, this extraordinary aftermarket system effectively transformed ordinary vehicles into rocket-powered dragsters.

Unlike conventional jet engines that produce thrust through continuous combustion, the Drag Axle employed a rocket turbine that directly drove the car’s rear wheels through a specialized differential housing.

What made the Turbonique system uniquely terrifying was its fuel: a proprietary mixture called “Thermolene” (essentially concentrated hydrogen peroxide) that spontaneously decomposed when passing over a catalyst, releasing tremendous energy without requiring ignition.

This monopropellant rocket technology could produce over 1,300 horsepower instantaneously, independent of the vehicle’s main engine.

When activated, the Drag Axle could propel an otherwise ordinary street car to speeds exceeding 160 mph in under 9 seconds performance figures that remained competitive with purpose-built dragsters for decades.

The system’s most famous implementation was “The Black Widow,” a Volkswagen Beetle modified with a Turbonique Drag Axle that reportedly achieved 9-second quarter-mile times a feat modern supercars with ten times the price tag still struggle to match.

However, the technology’s extreme nature led to numerous catastrophic failures. The uncontrollable power delivery, combined with chassis designs never intended for such forces, resulted in spectacular accidents including complete vehicle disintegration in several documented cases.

Regulatory intervention eventually ended Turbonique’s commercial availability by the early 1970s.

The combination of extremely dangerous fuel properties, minimal safety protocols, and the potential for catastrophic mechanical failure made these systems uninsurable liabilities.

Though short-lived, the Turbonique Drag Axle represents the most democratized application of jet propulsion technology in automotive history, allowing average enthusiasts to experience rocket-powered acceleration previously reserved for military test pilots.

Its legacy lives on in drag racing legend, representing an era when the boundaries between aerospace and automotive technology were remarkably porous, and consumer safety regulations remained in their infancy.

6. GM Firebird I XP-21 (1953)

The GM Firebird I XP-21 is one of the most audacious automotive concept vehicles ever created, representing General Motors’ most literal adaptation of jet aircraft technology to automobile design.

Revealed in 1953 at the Motorama auto show, this single-seat marvel was the first gas turbine-powered car developed in the United States.

The brainchild of legendary GM design chief Harley Earl and engineer Charles McCuen, the Firebird I wasn’t merely inspired by aircraft it was essentially a jet fighter without wings.

At its heart was an Allison J33 jet engine the same powerplant used in the Lockheed T-33 military trainer aircraft modified for automotive use and producing 370 horsepower.

Unlike later turbine cars that used the engine to generate electricity or drive conventional transmissions, the Firebird I employed direct thrust through a rear tailpipe, complemented by exhaust routed through side pipes that incorporated power turbines to drive the rear wheels.

This hybrid propulsion system created both jet thrust and mechanical power transfer simultaneously.

The vehicle’s aircraft lineage was unmistakable in every aspect of its design. The fiberglass body featured a needle nose, delta wing-inspired fins, a bubble canopy cockpit, and a vertical stabilizer reminiscent of contemporary fighter jets.

The driver operated the vehicle using aircraft-style controls including a joystick instead of a steering wheel.

The cooling air intake resembled a jet fighter’s nose cone, while the exhaust emerged from a genuine afterburner section at the rear.

Beyond its revolutionary propulsion system, the Firebird I incorporated numerous technological innovations including a regenerative braking system, titanium components, and independent suspension designed to handle the extreme forces generated by its unusual powerplant.

The car was fully operational not merely a static display though its extreme performance characteristics limited test driving to professional drivers on GM’s private test track.

While never intended for production, the Firebird I fulfilled its purpose as a technological showcase and publicity generator, cementing GM’s image as America’s most innovative automaker during the height of the Jet Age.

Its legacy extends beyond automotive history into American cultural consciousness, embodying the unbridled technological optimism and aerospace fascination that defined the post-war era.

Today preserved in GM’s Heritage Collection, the Firebird I remains one of the purest expressions of jet engine technology adapted for ground transportation.

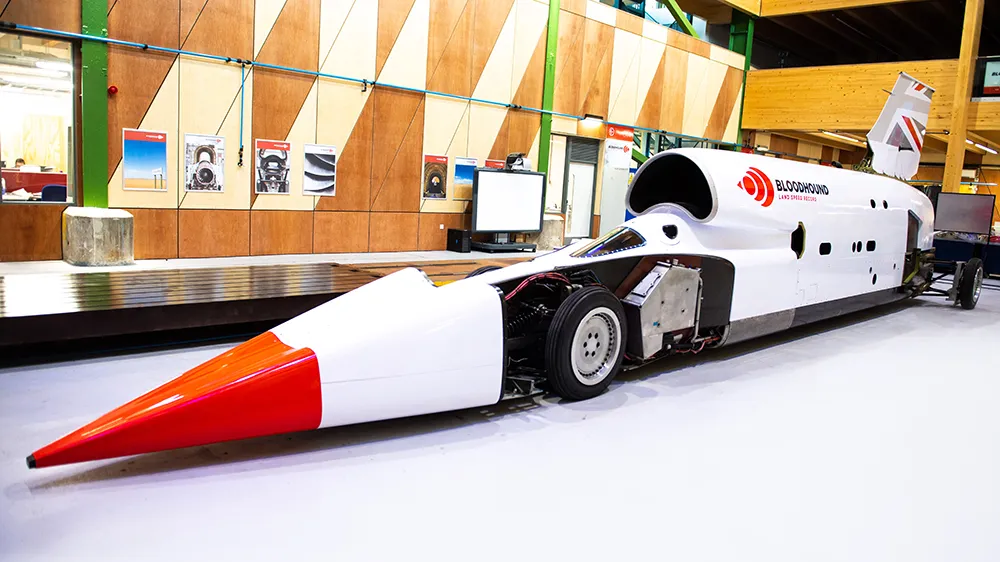

7. Bloodhound LSR

The Bloodhound LSR (Land Speed Record) is an extraordinary engineering marvel designed to redefine the boundaries of land-based speed.

This British-built supersonic car aims to break the land speed record by reaching beyond 800 mph (1,287 km/h), with the ultimate goal of achieving a groundbreaking speed of 1,000 mph (1,609 km/h).

The project is a blend of cutting-edge aerodynamics and advanced propulsion systems, showcasing innovation at its finest.

At the heart of the Bloodhound LSR is a Rolls-Royce Eurojet EJ200 afterburning turbofan engine the same engine used in the Eurofighter Typhoon jet.

This jet engine provides the car with immense thrust, capable of propelling it to unprecedented speeds.

Additionally, the car uses a cluster of rockets developed by Norwegian company Nammo for extra power during its record-breaking attempts.

Together, these systems generate over 135,000 horsepower, far surpassing the power of a Formula 1 car.

The car’s sleek, needle-like design is crafted to minimize aerodynamic drag and ensure stability at supersonic speeds.

Extensive testing has been conducted at the Hakskeen Pan desert in South Africa, where the Bloodhound LSR reached an impressive 628 mph (1,011 km/h) during its high-speed trials.

These trials are a testament to the car’s remarkable engineering and potential to make history.

More than just an attempt at breaking records, the Bloodhound LSR project serves as an inspiration for innovation in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

Its ambitious goals and engineering feats fascinate the imagination, encouraging the next generation of engineers and scientists to push the limits of human achievement.

8. Ford 999 Turbine Special (1963)

The Ford 999 Turbine Special represents one of racing’s most spectacular applications of jet engine technology.

Named in homage to Henry Ford’s early race car from 1902, this experimental machine was created specifically for the 1963 Indianapolis 500 and remains one of the most technologically audacious entries ever to appear at the Brickyard.

Under the direction of Ford’s engineering director Jack Passino, the company partnered with aircraft manufacturer AiResearch to develop a racing application for their T15 gas turbine engine, originally designed for helicopters and small aircraft.

The adapted powerplant generated 450 horsepower while weighing just 275 pounds creating an unprecedented power-to-weight ratio for its era.

Unlike conventional race engines that reached maximum power at specific RPM ranges, the turbine delivered nearly constant torque throughout its operating range, eliminating the need for a traditional transmission.

The car utilized a simple two-speed gearbox primarily serving as a reduction unit to manage the turbine’s naturally high operating speeds of over 44,000 RPM.

Aerodynamically, the 999 Turbine Special featured revolutionary packaging advantages. Without a conventional engine’s cooling requirements, engineers created a sleeker profile with minimal frontal area.

The turbine’s exhaust gases exited through four distinctive outlets in the car’s tail, creating an unmistakable visual and auditory signature.

Driver Jimmy Clark reported the car’s distinctive characteristics virtually no engine braking when lifting off the throttle, instantaneous torque delivery, and the absence of traditional vibration created a driving experience unlike anything in motorsport.

Despite its technological promise, race regulations stymied the 999’s potential. Officials imposed restrictive inlet area limitations specifically targeting turbine technology, effectively reducing the engine’s maximum potential output.

In qualifying, the car reached 151.153 mph respectably competitive but not revolutionary. Mechanical issues forced its retirement from the race after just 96 laps, with Clark reporting handling challenges from the unconventional weight distribution and power delivery characteristics.

Though its racing career proved brief, the Ford 999 Turbine Special maintained historical significance as the first major American manufacturer to attempt to bring jet engine technology to mainstream motorsport.

It foreshadowed the more successful STP-Paxton Turbocar who nearly won the Indianapolis 500 four years later.

Today displayed at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum, the 999 Turbine Special stands as a testament to Ford’s engineering ambition during an era when aerospace technology transfer represented the cutting edge of automotive performance development.

9. BAT 11 Turbine Concept (2008)

The BAT 11 Turbine Concept stands as one of automotive design’s most extraordinary fusion experiments, blending Alfa Romeo’s legendary Berlinetta Aerodinamica Tecnica heritage with revolutionary jet propulsion technology.

Revealed at the 2008 Geneva Motor Show, this breathtaking machine was created through a collaboration between Stile Bertone and a specialized engineering consortium led by Gary Kaberle, who owned one of the original BAT concepts from the 1950s.

While visually referencing its historical predecessors’ dramatic aerodynamic experimentation, the BAT 11 featured thoroughly modern propulsion through an advanced microturbine hybrid system.

The vehicle’s most revolutionary aspect was its powerplant a lightweight microturbine generator producing electricity for four in-wheel electric motors.

This arrangement enabled precise torque vectoring across all four wheels while eliminating conventional drivetrain components like transmissions and driveshafts.

The turbine unit operated within a narrow, optimal RPM range, generating electricity with minimal emissions while the electric motors handled the variable power demands of performance driving.

This innovative system delivered an estimated 700 combined horsepower while achieving efficiency impossible with conventional engines.

Aerodynamically, the BAT 11 represented a technological tour de force. Its dramatic bodywork wasn’t merely stylistic homage every curve, inlet, and sweeping surface served specific aerodynamic functions derived from aerospace engineering.

The distinctive tail fins, reminiscent of the original 1950s BAT series, were precisely calibrated to reduce drag while enhancing high-speed stability.

Active aerodynamic elements, including an adjustable rear spoiler and underbody diffusers, are automatically reconfigured based on speed and driving conditions technology directly adapted from jet aircraft.

Inside, the cockpit reflected aviation inspiration through a fighter jet-like instrumentation layout with a head-up display projecting critical information onto the windshield.

The driver controlled various powertrain modes through a joystick-inspired controller rather than conventional pedals and switches, creating an aircraft-like user experience aligned with the vehicle’s technological ethos.

While never reaching production, the BAT 11 Turbine Concept represented a fascinating exploration of how jet engine principles could be integrated into automotive design without sacrificing visual drama or historical connection.

Its innovative approach to microturbine hybrid technology foreshadowed later developments in extended-range electric vehicles.

Today, the concept remains privately owned, occasionally appearing at prestigious automotive exhibitions as a rolling testament to how aerospace technology can revolutionize automotive propulsion while honoring iconic design heritage.

10. Rover-BRM (1963-1965)

The Rover-BRM represents one of motorsport’s most sophisticated applications of jet engine technology to endurance racing.

Born from an unlikely collaboration between British car manufacturer Rover and British Racing Motors (BRM), this revolutionary machine competed in the most grueling race the 24 Hours of Le Mans using a gas turbine engine adapted from helicopter technology.

First appearing as an experimental entry in 1963 and later as a full competitor in 1964-65, the Rover-BRM stands as a pivotal moment in the convergence of aerospace and automotive engineering.

At the project’s heart was Rover’s 2S/150 gas turbine engine, which evolved from the company’s decade-long research into automotive applications for jet technology.

This extraordinary powerplant produced 150 horsepower while weighing significantly less than comparable piston engines.

Unlike conventional race engines requiring careful warming and maintenance, the turbine offered remarkable simplicity starting instantly regardless of temperature and running with minimal vibration throughout its RPM range.

The engine operated at temperatures exceeding 700°C and rotational speeds over 50,000 RPM, necessitating exotic materials and cooling solutions derived directly from aircraft applications.

What distinguished the Rover-BRM from other experimental racers was its comprehensive development and genuine competitiveness.

Driven by Formula 1 champions Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart in its most developed form, the car completed the 1965 Le Mans 24 Hours with extraordinary reliability, finishing 10th while averaging 98.8 mph.

The turbine’s unique power delivery characteristics particularly its instant torque and linear power band proved advantageous through Le Mans’ challenging corners, though top speed limitations from restricted inlet area regulations prevented it from matching the fastest conventional cars on the circuit’s long straights.

The car’s most revolutionary feature beyond its engine was its heat exchanger system a regenerative design that captured exhaust heat to pre-warm incoming air, dramatically improving fuel efficiency.

This technology, standard in aircraft turbines but revolutionary in automotive applications, helped the Rover-BRM achieve competitive fuel consumption despite the turbine’s naturally thirsty characteristics.

Additionally, the car pioneered advanced ceramic components capable of withstanding extreme thermal cycles, technologies that would later influence mainstream automotive development.

Though rule changes effectively banned turbine engines from competition by the late 1960s, the Rover-BRM accomplished its primary mission of demonstrating jet engine viability in extreme motorsport conditions.

The project generated invaluable data that influenced subsequent turbine research programs at multiple manufacturers.

Today preserved at the British Motor Museum, the Rover-BRM stands as perhaps the most thoroughly developed and successfully implemented adaptation of jet engine technology to competitive motorsport a perfect synthesis of British aerospace expertise and racing ingenuity.

11. Lotus 56 (1968)

The Lotus 56 represents perhaps the most sophisticated and technologically advanced adaptation of jet engine principles to motorsport competition.

Designed by the legendary Colin Chapman for the 1968 Indianapolis 500, this revolutionary machine employed a Pratt & Whitney ST6 gas turbine engine similar to those used in helicopters and small aircraft modified specifically for racing applications.

What distinguished the Lotus 56 from previous turbine experiments was its comprehensive integration of aerospace principles across every aspect of vehicle design, creating a holistic expression of jet age technology rather than merely an experimental powerplant in a conventional chassis.

The car’s most obvious aviation-derived feature was its wedge-shaped body with side-mounted radiators and distinctive air intake pods.

This aerodynamic profile, developed using principles from aircraft design, generated unprecedented downforce while minimizing drag critical for managing the turbine’s unique power delivery characteristics.

The chassis incorporated aircraft-grade aluminum and exotic composite materials capable of withstanding the extreme heat generated by the turbine, which operated at temperatures exceeding 1,800°F during peak operation.

Perhaps most revolutionary was the 56’s four-wheel-drive system a direct response to the turbine’s instant torque delivery.

Unlike conventional engines that built power progressively through their RPM range, the Pratt & Whitney powerplant delivered its approximately 500 horsepower almost instantaneously, necessitating power distribution to all four wheels for adequate traction.

This drivetrain configuration, combined with the turbine’s compact dimensions and low center of gravity, created handling characteristics decades ahead of contemporary race cars.

The Lotus 56’s potential was dramatically demonstrated during qualifying for the 1968 Indianapolis 500, where driver Graham Hill secured the second position on the starting grid. In the race itself, all three Lotus 56 entries showed exceptional speed before mechanical failures unrelated to the turbine engines sidelined them.

Joe Leonard was leading with just nine laps remaining when a fuel pump shaft failure, not the turbine itself—ended the car’s remarkable run.

Following the 1968 race, rule changes effectively banned turbine engines from Indianapolis competition by severely restricting intake dimensions.

Chapman adapted the design for Formula 1 as the Lotus 56B, achieving limited success before turbine technology was similarly restricted in Grand Prix racing.

Despite its brief competitive career, the Lotus 56 stands as motorsport’s most holistic integration of jet technology, influencing subsequent race car development through its aerodynamic principles, all wheel drive configuration, and monocoque construction techniques.

Examples preserved in museums today represent one of motor racing’s most ambitious technological leaps the moment when aerospace and automotive engineering achieved their most complete synthesis.

12. General Electric Jet Engine Testing Car (1946)

The General Electric Jet Engine Testing Car stands as both the earliest and most literal adaptation of jet engine technology to automotive applications.

Developed immediately following World War II, this extraordinary machine wasn’t created as a supercar or even a speed record contender rather, it served as a critical mobile test platform for America’s nascent jet engine program during a pivotal moment in aviation history.

Despite its utilitarian purpose, this remarkable vehicle deserves recognition as the true progenitor of all subsequent jet-powered automobiles.

The project began in 1946 when GE engineers needed a way to test early jet engines without the expense and complexity of aircraft installation.

Their solution was ingeniously straightforward: mount a full-size I-16 turbojet engine (later designated J31) the first jet engine mass-produced in America onto a heavily modified 1939 Dodge sedan.

The car’s entire rear section was removed and replaced with a specialized mounting frame capable of withstanding the engine’s 1,600 pounds of thrust.

A comprehensive instrumentation package monitored every aspect of the jet’s performance during mobile testing.

What made this vehicle unique among jet-powered cars was its purpose. Unlike later speed record attempts, the GE car wasn’t designed primarily for velocity but for realistic simulation of takeoff and landing conditions.

By driving at precisely controlled speeds on airport runways, engineers could measure engine performance under actual air intake conditions impossible to replicate in stationary test cells.

The car regularly operated at speeds between 30-90 mph modest by later standards but perfectly suited for simulating aircraft taxi, takeoff, and landing scenarios.

The most remarkable aspect of the GE Testing Car was its contribution to aviation development.

Engines tested on this platform directly influenced designs that powered America’s first operational jet fighters, including the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star.

The mobile test bed identified critical issues with flame stability, acceleration lag, and temperature management that stationary testing couldn’t reveal.

These discoveries fundamentally shaped subsequent jet engine development, accelerating America’s aerospace capabilities during the critical early Cold War period.

Though never designed for public display or performance demonstration, the GE Testing Car represents the purest transfer of jet technology to ground transportation using an unmodified aircraft engine in its intended operational mode, merely with wheels beneath it instead of wings.

While later supercars would adapt turbine principles for automotive use, this pioneering machine employed actual aircraft hardware for its original purpose, creating the conceptual bridge between aerospace and automotive engineering that all subsequent jet-powered vehicles would follow.

Today preserved in General Electric’s corporate archives, this unassuming modified Dodge remains the true ancestor of every turbine-powered car that followed.

Also Read: 12 Naturally Aspirated Supercars That Sound the Best