The world of motorsport is a theater of speed, precision, and relentless engineering progress. Beneath the roar of the engines and the glamor of the grandstands lies a brutal truth: not every idea is welcome, and not every innovation is immediately embraced.

Many revolutionary technologies begin their lives as discarded concepts—dismissed by manufacturers, sidelined by budget constraints, or shelved by teams unwilling to take a risk. One such story stands out in racing history, not just for the technical achievement but for the sheer audacity of its journey from rejection to legacy.

This is the story of how a dismissed engine design—the Cosworth DFV—reshaped the trajectory of Formula One racing and etched its name permanently into motorsport lore.

The 1960s were a transformative era for Formula One. The sport was moving away from the brutish machines of the past and leaning into lighter, more refined engineering philosophies. Engine design became a frontier of innovation.

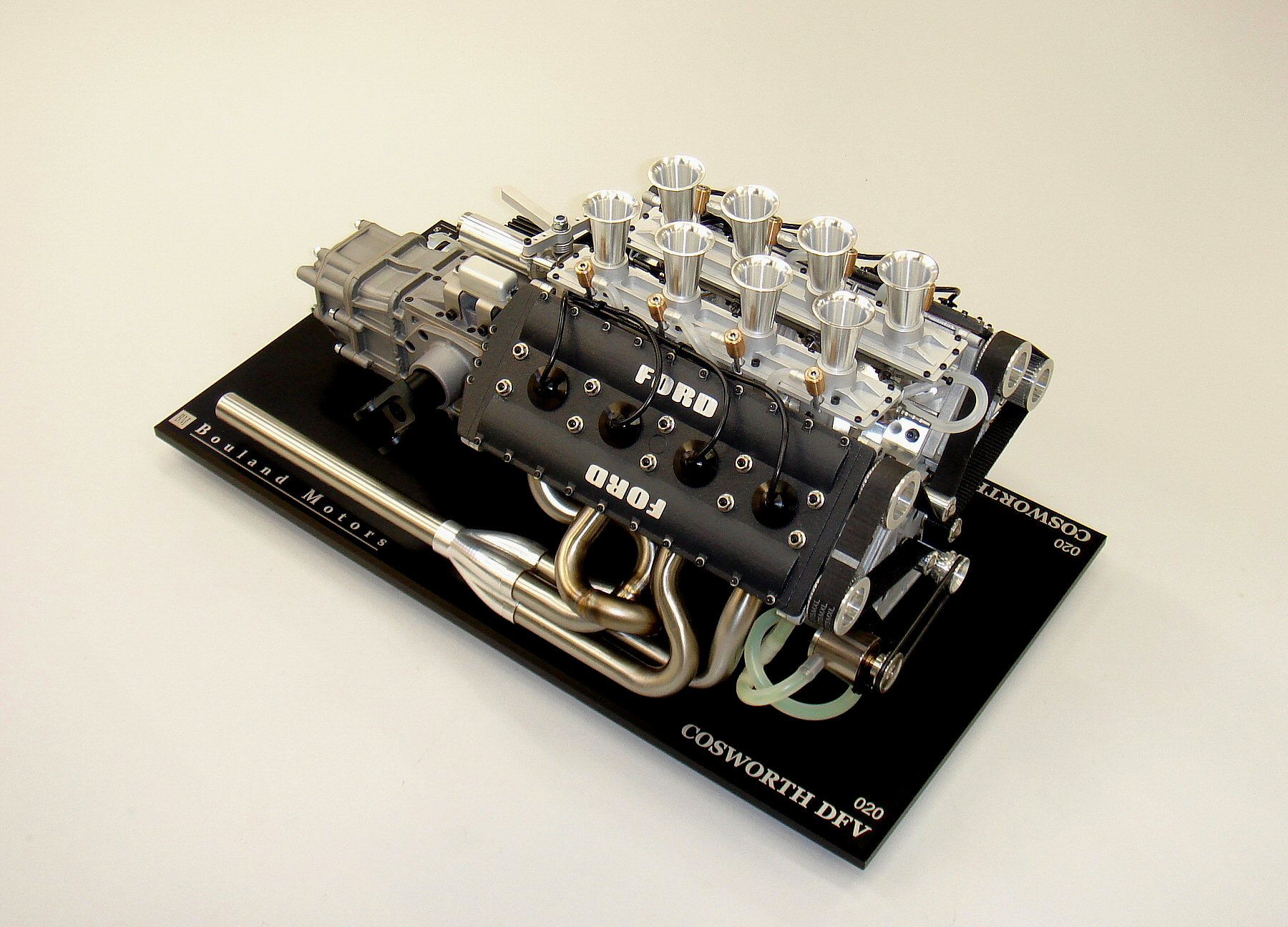

Against this backdrop, Keith Duckworth, co-founder of Cosworth Engineering, envisioned an engine that was not only powerful and lightweight but also designed with a unique integration into the car chassis. His idea was radical: a V8 engine that would double as a structural component of the car, eliminating the need for a traditional frame in certain areas and reducing overall weight.

Also Read: 5 Cars That Hold Their Price After 3 Years and 5 That Tank Fast

Duckworth’s proposal was initially rejected by many of the established automotive giants. Manufacturers viewed the design as too risky, too unproven. Yet, it caught the attention of Colin Chapman, the visionary founder of Lotus. Chapman recognized that the engine’s design fit perfectly with his own minimalist design philosophy.

With backing from Ford—thanks to some clever lobbying and reputation leverage—the Cosworth DFV was born. What followed was nothing short of a revolution.

This article explores how a bold, initially rejected engine design changed the face of racing. From its origins in a small engineering firm to its dominance on the world’s fastest circuits, the DFV’s journey is one of persistence, innovation, and the courage to believe in a better way. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the ideas the world first ignores are the very ones that make history.

The Origins of the DFV: An Idea Ahead of Its Time

The story begins in the mid-1960s, when the need for a new Formula One engine was becoming increasingly apparent. At the time, Coventry Climax, a prominent supplier of engines to several F1 teams, was withdrawing from racing. This left a critical gap in the supply of competitive power units.

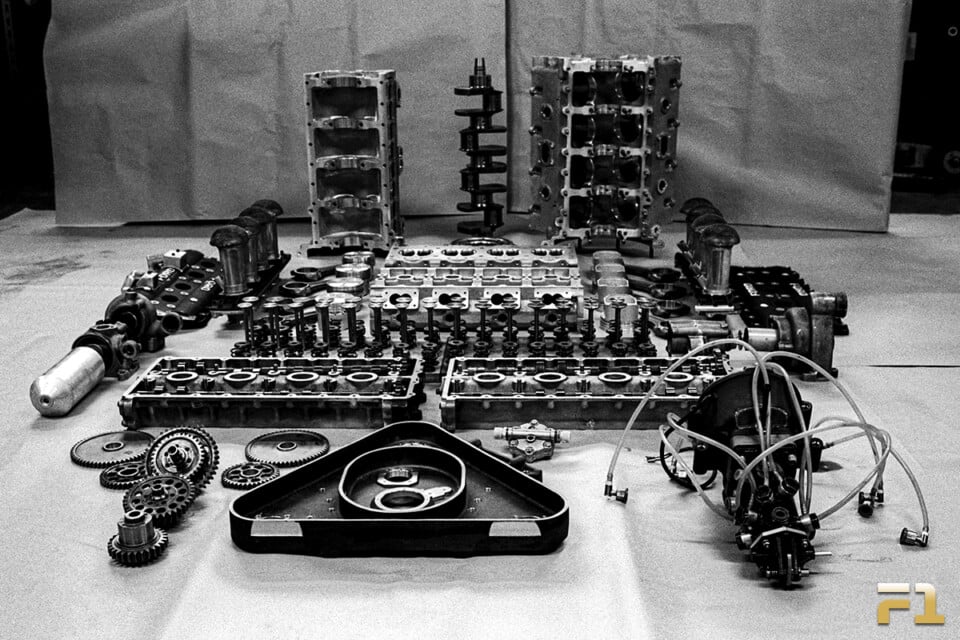

Keith Duckworth and Mike Costin, the brains behind Cosworth Engineering, saw an opportunity. Duckworth began designing an engine that would not only provide superior performance but also be reliable and relatively inexpensive compared to its contemporaries. His vision was a 3.0-liter V8 engine, compact, powerful, and modular.

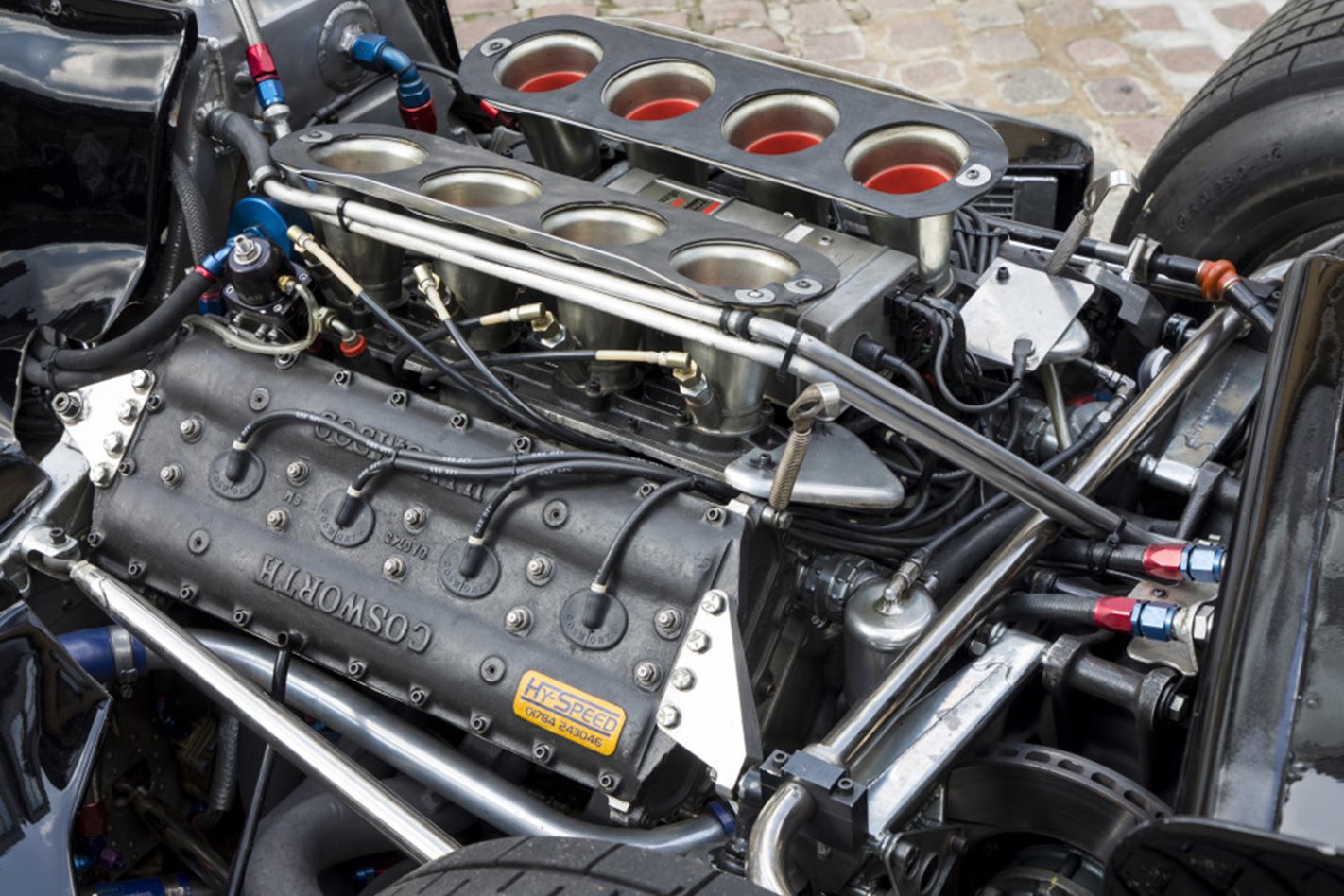

One of the most revolutionary aspects of the proposed design was its integration into the chassis. Rather than being mounted into a supporting frame, the engine itself would act as a stressed member, forming part of the car’s structural backbone. This approach significantly reduced weight and allowed for better weight distribution—key advantages in the high-stakes world of Formula One.

The concept, while elegant in its simplicity, was met with skepticism. Many teams were hesitant to abandon the traditional design principles that had defined racing cars up to that point. Additionally, Cosworth was still relatively small and lacked the reputation of established engine manufacturers.

Despite these challenges, Duckworth persisted. He knew the design had merit, and he continued refining it, confident that he just needed the right partner to bring the concept to life. That partner arrived in the form of Colin Chapman of Lotus. Chapman, always one to chase the edge of innovation, saw the potential in Duckworth’s idea.

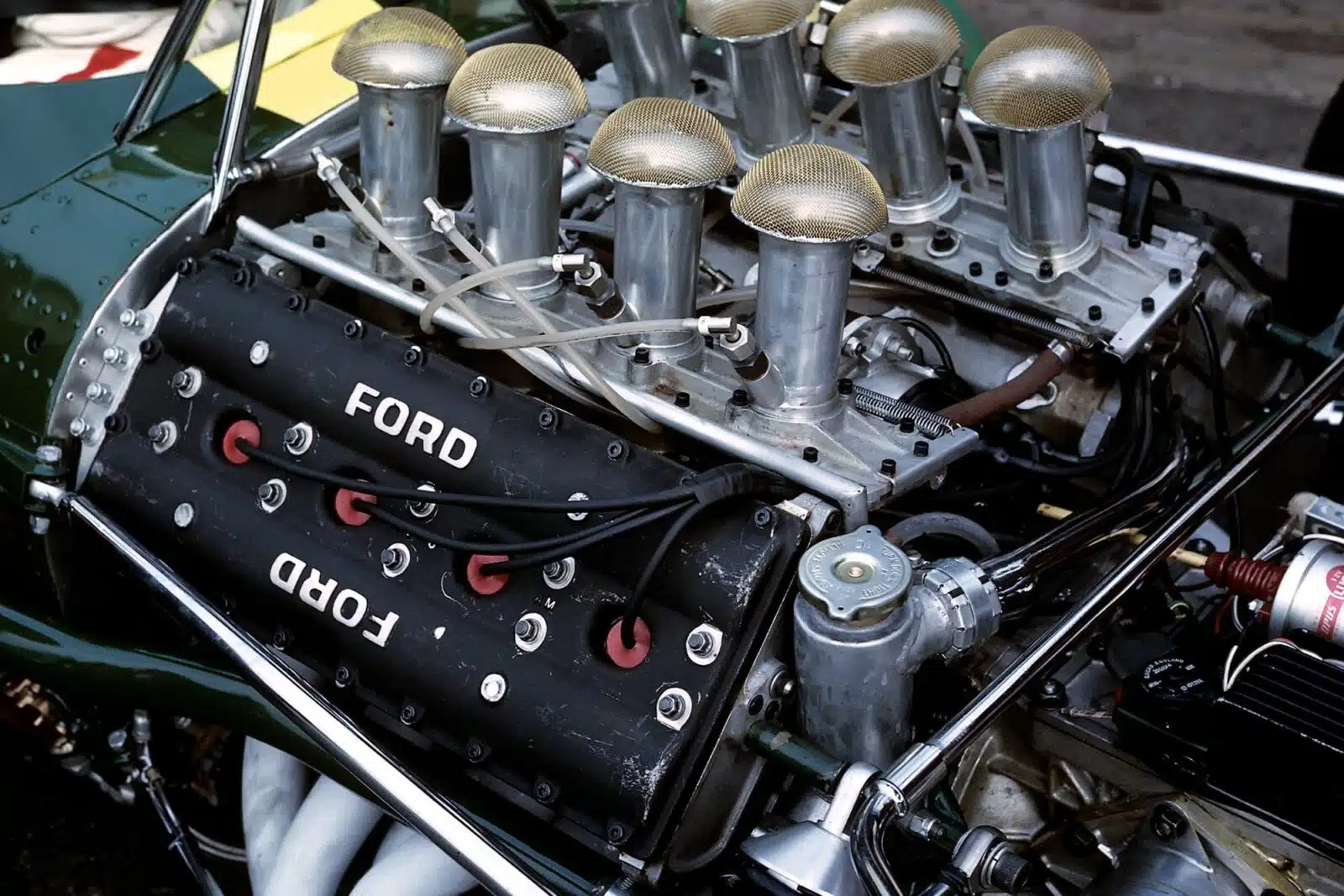

He believed in lightness, in integration, and in the value of a unified design philosophy between chassis and engine. More importantly, Chapman had connections at Ford, and he convinced the company to fund the development of the engine for exclusive use by Lotus. Thus, the DFV—Double Four Valve—was born, its name derived from its dual overhead camshafts and four valves per cylinder.

The First Victory: A Debut That Shook the World

The DFV made its debut in the 1967 Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort. Fitted into the Lotus 49 and driven by the legendary Jim Clark, the engine did more than perform—it dominated.

Clark won the race convincingly, showcasing the power and reliability of the DFV. This was more than a victory; it was a statement. In its very first outing, a rejected design had not only held its own—it had triumphed over established giants like Ferrari and BRM. The DFV’s blend of high revving capability, light weight, and compact size gave it an immediate edge.

The Lotus 49’s performance demonstrated that the DFV’s innovative integration into the chassis worked not just in theory but in real-world racing conditions. It changed the design logic for F1 teams almost overnight.

Teams realized they no longer needed a heavy spaceframe or monocoque structure behind the cockpit. With the DFV acting as a structural member, cars could be lighter, more agile, and easier to repair. This breakthrough in design sparked a fundamental shift across the grid, as teams scrambled to adapt similar principles.

Clark’s victory at Zandvoort was just the beginning. The DFV went on to power Lotus to multiple victories throughout the season. More importantly, it proved to the racing world that innovation could triumph over tradition. The engine’s success quickly caught the attention of other teams, many of whom began lobbying for access to the DFV.

In a move that would define an era, Ford and Cosworth eventually allowed other constructors to purchase the engine, transforming it from a Lotus-exclusive weapon to a universal contender. This marked the beginning of the DFV’s dominance, and it became the de facto engine of Formula One for more than a decade.

Dominance Redefined: The DFV Era in Full Swing

From 1967 to the early 1980s, the Cosworth DFV became the backbone of Formula One. It wasn’t just one team using it—it was nearly every team not backed by a major manufacturer. The engine powered cars to 155 Grand Prix victories and won 12 Drivers’ Championships and 10 Constructors’ Championships.

Its modularity, ease of maintenance, and affordability made it the ideal engine for privateers and smaller constructors, democratizing access to competitive racing. The era of the DFV is often remembered as the golden age of F1, not only because of the talent on the grid but also because of the engine that made competitive parity possible.

The DFV’s design allowed it to be easily integrated into a variety of chassis, which led to a surge in innovative designs across the paddock. Teams like Tyrrell, McLaren, Williams, and March built winning cars around the engine. Each team interpreted the chassis differently, but the DFV remained the constant heartbeat.

This enabled technical creativity without the added burden of developing a proprietary powertrain. The engine could rev to over 10,000 RPM and delivered more than 400 horsepower—more than sufficient for the lightweight, nimble cars of the time.

The dominance of the DFV changed the political and technical landscape of F1. For over a decade, the championship was not won by the team with the biggest factory budget but by the team that best optimized the DFV and chassis integration. It also gave rise to independent engineers and designers who could now compete with the sport’s biggest names.

The DFV turned F1 into a sport where genius could outmatch money—a rare dynamic in motorsport. And all this came from an engine that many initially dismissed as too radical, too different, or too ambitious to succeed.

The Legacy of Innovation: Beyond the Checkered Flag

The influence of the DFV extended far beyond the podiums and championships it helped secure. It changed how engines were conceptualized in motorsport and set the blueprint for future integration between engine and chassis.

While turbocharged engines eventually replaced the DFV in the 1980s due to shifting regulations and technology, its core principles lived on. The idea of the engine as a structural component became standard, and its lightweight, high-revving philosophy influenced generations of engine design across multiple racing disciplines.

Moreover, the DFV proved that independent engineering firms could play a central role in motorsport innovation. Before Cosworth’s success, engine development was largely dominated by automotive manufacturers with vast resources. The DFV changed that.

Cosworth became a name synonymous with performance, opening the door for future collaborations between small engineering companies and racing teams.

It created a template for how technical partnerships could disrupt established hierarchies in the sport. Other racing series, including IndyCar and endurance racing, also took cues from Cosworth’s modular and cost-effective approach.

Even today, the DFV is revered as one of the greatest engines ever built. Examples of it continue to run in historic racing events, where its characteristic sound and performance still captivate fans. More importantly, the DFV serves as a reminder that innovation does not always come from the top.

Sometimes, it comes from outsiders with conviction, designers unafraid to challenge convention, and partnerships willing to take a chance on the seemingly impossible. The DFV’s story is a legacy of engineering courage—and a testament to how rejection can be the first step toward greatness.

Lessons in Risk and Reward: What Modern Racing Can Learn

The tale of the DFV is not just a chapter in motorsport history—it is a case study in innovation, risk-taking, and the power of unconventional thinking.

In an era where Formula One is increasingly dominated by mega-manufacturers and intricate hybrid power units, the story of a relatively small firm like Cosworth creating an engine that ruled the sport for over a decade is both inspiring and instructive. It teaches that the most impactful innovations often stem from a willingness to depart from tradition and embrace the untested.

For modern teams, the DFV’s success offers several lessons. First, technical integration between systems can unlock performance that is greater than the sum of its parts. The DFV wasn’t just an engine—it was part of the car’s DNA. Second, partnerships are crucial.

Also Read: 5 Cars With Smart Tech That Actually Works and 5 That Glitch Out

Without Colin Chapman’s belief in Duckworth’s vision and Ford’s financial backing, the DFV would likely never have been built. Innovation thrives when engineers, designers, and financiers align behind a shared goal. Third, accessibility matters. The DFV showed that standardized technology, when done right, can enhance competition rather than diminish it—a principle still relevant in discussions around cost caps and shared components today.

Finally, the DFV reminds us that legacy is not built overnight. It took boldness to design it, courage to fund it, and genius to race it. But above all, it took resilience to stand by an idea that others had turned away.

In racing—as in life—the difference between failure and triumph often lies not in the rejection, but in the response. The DFV engine wasn’t just a mechanical marvel; it was a symbol of what’s possible when belief, innovation, and opportunity come together.