The world of engine rebuilding is filled with equal parts excitement, confusion, and decision-making. For every seasoned gearhead who knows exactly what engine to pull from a junkyard, countless enthusiasts and first-time builders are staring at greasy blocks, wondering if their chosen platform is worth the hours, money, and energy it will take to bring it back to life.

And when it comes to Chevrolet engines — perhaps the most iconic and ubiquitous powerplants in American automotive history — that decision can be even more difficult.

Chevrolet has built dozens of engines since the dawn of the automobile age. From the barebones inline-fours of the 1920s to the big-block bruisers of the muscle car era, and to today’s technologically advanced LS and LT platforms, Chevy engines have powered everything from grocery-getters to championship-winning race cars.

This diversity is what makes Chevrolet so compelling — and so complicated. You could be handed a V8 core from a friend or inherit a car with a blown motor, and without a deep understanding of that engine’s history and potential, you might end up spending months rebuilding something that was never worth touching in the first place.

There’s a romantic allure to rebuilding an engine. It’s not just about horsepower. It’s about the tactile joy of putting metal back together, of making something run again that others would scrap.

It’s a rite of passage in the automotive world. But rebuilding a poor platform doesn’t make you a hero — it often makes you broke, frustrated, and disillusioned.

That’s why choosing the right engine matters more than ever, especially in an era where high-performance crate engines and modern swaps are more accessible than they’ve ever been.

This article dives into the heart of that decision by looking at five Chevrolet engines that are absolutely worth rebuilding, and five that simply are not.

This isn’t just a matter of preference or brand loyalty — this is based on real-world metrics like performance potential, parts availability, reliability, historical value, and community support. Some engines have proven themselves over decades as bulletproof performers, while others are best left to rest in peace under a layer of junkyard dust.

The “worth rebuilding” engines we explore are not just legends — they’re flexible, fun, and rewarding platforms that offer value whether you’re building a weekend cruiser, a drag car, or a classic showpiece.

These engines have strong aftermarket ecosystems, proven upgrade paths, and widespread documentation, making them excellent choices for both beginners and experienced builders. They’re the kinds of engines that will teach you why people love internal combustion and make your time in the garage feel meaningful.

On the flip side, some engines are more curse than blessing. These motors might seem like an easy or cheap rebuild project on the surface, but they are bogged down by poor design, underwhelming performance, and limited upgrade options. Some were built during desperate eras when fuel efficiency and emissions strangled creativity.

Others were simply budget-focused, never intended to be rebuilt or celebrated. Whatever the reason, putting money into the wrong engine can turn a fun project into a massive regret, and we’re here to help you avoid that.

Whether you’re staring down your first rebuild or looking for a new engine to swap into your next project car, this guide will give you clarity.

Rebuilding an engine can be a rite of passage, a personal triumph, and a deeply satisfying experience — but only if you start with the right block, the right platform, and the right plan. Let’s break down the Chevys that deserve your time — and those that deserve the scrap heap.

ALSO READ: 5 Minivans With Awkward Middle Row Access and 5 That Get It Right

5 Chevrolet Engines Worth Rebuilding

1. Chevrolet 350 Small Block V8 (SBC)

The Chevrolet 350 small block is the quintessential American V8 engine and arguably the most iconic engine General Motors has ever produced. It made its debut in 1967 and quickly became a staple across a vast lineup of Chevrolet vehicles, including Camaros, Corvettes, Novas, pickups, and even station wagons.

What makes the 350 so revered isn’t just its widespread usage — it’s the perfect blend of size, power, simplicity, and tunability. Its basic architecture remained largely unchanged for decades, cementing its status as a foundational engine in the performance and restoration world.

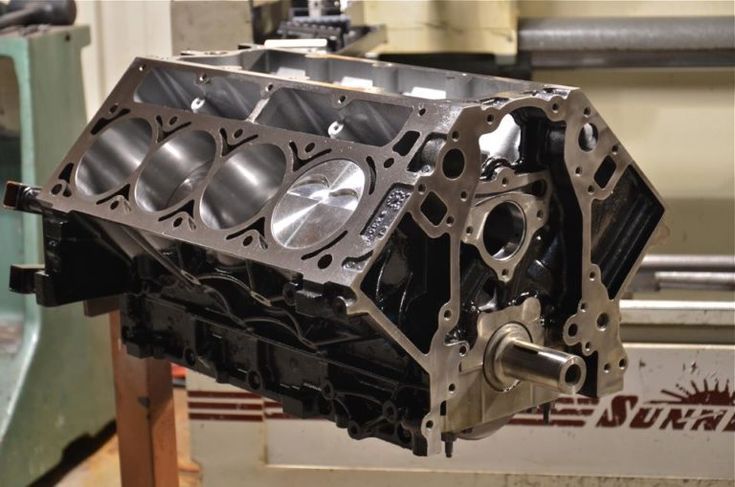

One of the key reasons the 350 is worth rebuilding is its simplicity and robust design. With a traditional cast iron block, straightforward valvetrain, and easily serviceable components, it provides an ideal learning platform for amateur builders while also being powerful enough for seasoned pros to get creative with.

It responds well to traditional performance upgrades like camshaft swaps, higher-flow cylinder heads, and more aggressive carburetion or EFI systems. Whether you want to keep it mild or go wild, the 350 can accommodate nearly any vision.

The aftermarket support for the 350 is unparalleled. You can build a 350 entirely from brand-new aftermarket parts without using a single piece from the original engine.

That’s how popular and well-supported it is. Cylinder heads, intake manifolds, cam kits, rotating assemblies, and ignition systems are all widely available at every price point.

Because of its interchangeability with other small block engines, it’s also compatible with a huge range of vehicles and accessories, making swaps and rebuilds much simpler and more cost-effective.

From a cost perspective, rebuilding a 350 is one of the most affordable ways to get into V8 performance. Core engines are plentiful in junkyards, parts cars, and even Craigslist barn finds.

The simplicity of the design means machine work is generally straightforward, and the sheer volume of parts means you can shop around to find deals or premium components based on your budget. It also offers high value retention if you’re restoring a classic or flipping a project car.

Most importantly, a rebuilt 350 brings satisfaction beyond specs. There’s a sense of legacy and tradition in working on this engine — it connects you to generations of hot rodders, drag racers, and weekend warriors.

Whether you’re restoring a 1969 Chevelle or building a custom rat rod, the 350 small block V8 continues to be one of the most reliable, versatile, and rewarding engines you can put your time and money into rebuilding.

2. LS1 (Gen III Small Block)

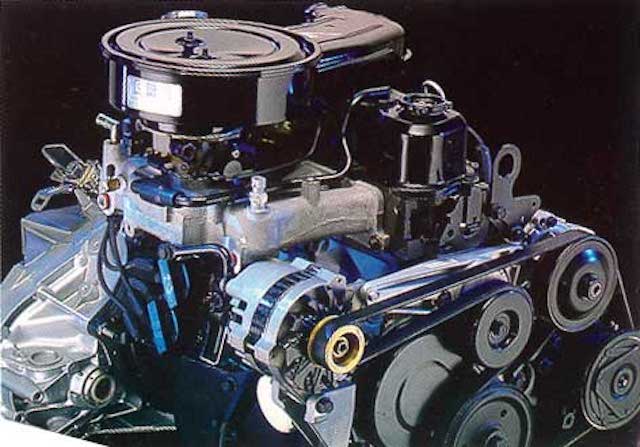

The LS1 engine was a game-changer when it debuted in 1997 under the hood of the Corvette C5. At 5.7 liters, it delivered high performance in a compact, lightweight package thanks to its all-aluminum construction — a revolutionary move for a production GM V8 at the time.

Not only did it make an impressive 345 horsepower in stock form, but it also set the stage for the entire LS engine family, which has now become one of the most popular platforms for swaps and custom builds worldwide.

Rebuilding an LS1 is often the gateway into the modern performance world. Unlike older engines, the LS1 was engineered with performance and modularity in mind.

The cathedral-port heads, high-flow intake manifold, and strong bottom end give it excellent performance out of the box, and even more when enhanced with aftermarket parts. It’s a true balance between old-school V8 charm and modern EFI precision, which is why so many builders choose it for restomods and track cars alike.

One of the LS1’s most significant advantages is its compatibility with the broader LS engine family. Many components, such as camshafts, intake manifolds, fuel rails, and heads, can be swapped between LS-series engines with little or no modification.

This opens up a world of possibilities when rebuilding the LS1. For example, you can port a set of LS6 heads or install an aftermarket cam kit to dramatically improve power output without changing the block.

Despite being a high-performance engine, rebuilding an LS1 doesn’t have to break the bank. OEM parts are still relatively affordable, and the aftermarket is flooded with upgrade options ranging from mild street cams to full forged rotating assemblies for turbo builds.

If you’re already sourcing a core from a donor Corvette, Camaro, or Trans Am, you’re halfway there. Performance shops and forums provide ample support to guide builders through everything from basic rebuilds to full race-prepped configurations.

In terms of long-term investment, the LS1 is rock-solid. Whether you’re using it in a Corvette, swapping it into a vintage Nova, or powering a track-focused Miata, the LS1 offers consistent reliability, tuning flexibility, and resale value.

If you’re looking to step into the modern era of engine technology while still retaining the soul of a true V8, the LS1 is easily one of the best Chevrolet engines worth rebuilding.

3. 454 Big Block V8 (Mark IV Series)

The Chevrolet 454 is the embodiment of American big-block brute force. Introduced in 1970 as part of the Mark IV engine family, the 454 cubic inch V8 was created during the golden age of muscle cars and became synonymous with raw torque and big power.

Found in the Chevrolet Chevelle SS, El Camino, Corvette, and later in heavy-duty trucks, this engine was built to dominate both the street and the strip.

Rebuilding a 454 is all about unleashing its massive displacement. With nearly 7.5 liters of displacement and a bore/stroke combination that prioritizes torque, the 454 is capable of producing mountains of low-end grunt. Even in stock form, it’s a torque monster.

Once you rebuild it with higher-compression pistons, a performance cam, and a better-flowing intake and exhaust setup, the power curve becomes monstrous. It’s not unusual to see street builds push 600 horsepower or more without exotic parts.

One of the greatest appeals of the 454 is its mechanical strength. The forged steel crankshaft, stout connecting rods, and thick cylinder walls make it a favorite for high-horsepower builds, especially in the world of drag racing and truck pulling.

Many enthusiasts choose to reinforce the bottom end during a rebuild to accommodate forced induction, such as a roots-style blower or turbo, capitalizing on the engine’s ability to handle extreme loads.

The availability of aftermarket parts for the 454 is excellent. From aluminum cylinder heads to full roller valvetrain kits and tunnel ram intake manifolds, builders have limitless potential to tailor this engine to their needs.

Additionally, there’s something inherently satisfying about building a big-block engine: the physical presence, the rumble, and the sense of power are unmatched. Few engines make the same visceral impact as a properly rebuilt 454.

Of course, the 454 isn’t ideal for every application — it’s big, heavy, and can be thirsty. But for those looking to build a classic American muscle car or a show-stopping street machine, the 454 is a project that pays off in grins, growls, and gasps. Its unique blend of heritage and raw power ensures that a properly rebuilt 454 will always have a place among the greats.

4. Chevrolet 283 Small Block V8

The Chevrolet 283 small block V8, introduced in 1957, holds a legendary place in the annals of automotive history. As one of Chevrolet’s earliest small blocks, the 283 set the tone for generations of compact V8s to come. It was small, simple, and remarkably efficient for its time, producing anywhere from 185 to 315 horsepower depending on configuration.

It was the first production engine to achieve the magical “one horsepower per cubic inch” milestone — a major feat when the fuel-injected version debuted in the 1957 Corvette.

Rebuilding a 283 is less about chasing maximum horsepower and more about honoring the engine’s place in history. This engine is beloved by classic car restorers who want period-correct powerplants for their Bel Airs, Corvettes, and Impalas.

Unlike modern V8s that prioritize efficiency or maximum output, the 283 delivers a smooth, refined driving experience with classic mechanical character. It’s not about dominating dyno sheets — it’s about authenticity, sound, and the simple joy of driving a perfectly balanced vintage V8.

Despite its age, the 283 is a relatively straightforward engine to rebuild. It shares much of its architecture with the later 327 and 350 engines, which makes many replacement parts interchangeable or easily adapted.

You’ll find OEM and aftermarket support for pistons, camshafts, lifters, timing sets, and even upgraded heads. Its compact size also makes it a great candidate for tight engine bays where a big block or tall-deck engine simply won’t fit.

While the 283 won’t deliver modern horsepower levels, it can be built into a very reliable and respectable cruiser engine. Mild performance upgrades such as a slightly hotter cam, better heads, and a four-barrel carb or aftermarket EFI system can wake it up while still keeping the period feel.

You’ll often see rebuilt 283s making a comfortable 250–300 horsepower with great drivability and classic sound, making them ideal for daily-driven classics or weekend show cars.

There’s also the emotional and cultural value of rebuilding a 283. You’re not just putting an engine together — you’re reviving a chapter of American engineering history. For vintage Chevy enthusiasts, a properly rebuilt 283 is a jewel under the hood, capturing the spirit of post-war innovation and the birth of true American performance. It may not be the flashiest engine on this list, but it’s undoubtedly one of the most heartfelt rebuilds you can undertake.

5. 6.0L LQ4 / LQ9 (Gen III Iron Block LS-Based Engines)

The LQ4 and LQ9 6.0L V8s are often overshadowed by their aluminum LS cousins, but make no mistake — these iron-block LS-based engines are absolute beasts when it comes to performance per dollar.

Found in GM’s HD trucks and SUVs between 1999 and 2007, they combine the modern engineering of the LS platform with a rugged, heavy-duty construction that makes them perfect for high-power builds and budget-minded swaps.

What makes these engines particularly valuable for rebuilding is their strength. Unlike the LS1 or LS6, which use aluminum blocks for weight savings, the LQ4 and LQ9 use cast iron, which adds weight but significantly improves strength and durability, especially in forced induction applications.

Many high-horsepower drag and drift builds start with a junkyard LQ4 or LQ9 because of its ability to handle 800+ horsepower with proper internals.

The LQ4 (9.4:1 compression) and LQ9 (10:1 compression) share many parts with other Gen III LS engines, meaning that aftermarket support is just as strong as any LS1 or LS3. They benefit from the easy availability of performance cams, intake manifolds, cylinder heads, and tuning tools.

The stock truck intake is known to be a solid performer, and swapping in a set of high-flow heads or upgrading to an LS6 cam can yield impressive results. Best of all, these upgrades are usually plug-and-play thanks to the LS family’s standardized architecture.

From a rebuilding perspective, the LQ4 and LQ9 are solid choices because of their widespread availability and low initial cost. Junkyards across the country are full of these engines, often pulled from high-mileage Silverado HDs, Escalades, or Denali trucks.

Even a worn-out core can be rebuilt for a few thousand dollars into a powerplant that rivals far more expensive crate engines. Because of the engine’s iron block, it’s also more tolerant of boring and stroking during the rebuild process.

Finally, the LQ4 and LQ9 are a favorite among engine swappers because of their versatility. They can be fitted into muscle cars, trucks, off-road rigs, and even import vehicles with the right mounts and accessories. The tuning options are extensive, and with a simple harness and ECU reflash, you can run these engines with modern reliability and old-school brawn.

For any builder looking for raw strength, modern support, and incredible bang for the buck, rebuilding a 6.0L LQ4 or LQ9 is a decision that pays off in power and pride.

5 Chevrolet Engines Not Worth Touching

1. 305 Small Block V8

The 305 Small Block V8 was Chevrolet’s answer to rising fuel economy concerns in the late 1970s and early 1980s. While it shared much of its basic architecture with the legendary 350, the 305 was designed with a smaller bore (3.736 inches compared to the 350’s 4.000), which significantly limited its performance ceiling.

Found in everything from Monte Carlos to Camaros to full-size pickups, the 305 was an economy-oriented engine disguised as a V8, which is exactly why it’s a poor choice for performance-minded rebuilds.

The most frustrating part of rebuilding a 305 is that you can do everything right — replace all internals, upgrade the cam, add better heads, and install a modern intake system — and still be left with an underwhelming powerplant.

The restrictive heads, small bore, and limited airflow capacity mean it simply can’t match the power potential of a 350 or any LS-based engine. Even with forced induction, the returns are mediocre, especially when you factor in the cost of parts and machining.

Another major drawback is parts compatibility and cost-effectiveness. While many 305 parts are interchangeable with the 350, the performance aftermarket focuses on the latter. This means high-performance heads and pistons are either custom-made for the 305 or require compromises in compression or flow.

If you’re already investing in new heads and pistons, why start with a small-bore engine that bottlenecks power? Most builders eventually regret pouring resources into a 305 when a 350 or LS engine swap would’ve made more sense from day one.

There’s also a persistent misconception among beginners that because it’s a V8, the 305 must have potential. In truth, it’s often called the “350’s weaker cousin” for a reason.

The 305 was never designed with performance in mind; it was a stop-gap engine for emissions compliance and economy. While it may have been fine for daily drivers in the 1980s, it’s outclassed by almost every modern or classic performance engine today.

Unless you’re rebuilding a rare car that originally came with a 305 and you’re aiming for a 100% period-correct restoration, there’s virtually no scenario in which rebuilding a 305 makes sense.

It’s an engine that might start cheap but ends up costing more than it’s worth, both in time and money. In almost every situation, the 305 is better off replaced than rebuilt.

2. 267 Small Block V8

The 267 cubic inch V8 is perhaps the most forgettable member of the small block Chevy family. Introduced in 1979, Chevrolet attempted to create a fuel-efficient V8 during the height of the emissions and fuel crisis era.

Built on the same platform as the 350 and 305, the 267 featured a smaller bore and limited power output that made it one of the most sluggish and uninspired V8s ever built. Unfortunately, its existence has led many novice builders to assume it shares the performance potential of other SBC engines, which it simply does not.

The engine’s small bore (3.500 inches) severely restricts the valve sizes you can use, which in turn limits airflow and combustion efficiency. No matter how much work you put into the top end — even with aftermarket heads, intake, and a hot cam — the 267’s restricted breathing capacity means you’ll always be fighting a losing battle.

It’s not uncommon for rebuilders to throw thousands of dollars into a 267 and still end up with a power output that barely scratches 200 horsepower.

Beyond its poor performance potential, the 267 also suffers from a general lack of aftermarket support. While many parts do cross over from the broader small block family, high-performance components like pistons, heads, or stroker kits are almost nonexistent, specifically for the 267.

Machine shops familiar with performance SBC builds often raise eyebrows when you mention this engine, and most will tell you up front that you’re better off scrapping it and finding a better base.

There’s also minimal demand for rebuilt 267s. You won’t find anyone online or at car shows raving about their 267-powered G-body.

Even the restoration crowd largely avoids it, as many period-correct builds opt to swap in a 305 or 350 for better drivability without sacrificing too much originality. It’s an engine that has neither collector value nor street performance — a true black hole of effort.

In short, rebuilding a 267 is like trying to win a race on crutches. There’s no realistic payoff, and every dollar you spend only widens the gap between what you’ve invested and what you could have achieved with a better engine.

It’s one of the rare V8s that truly has no place in a performance or enthusiast build. If you come across one, admire its oddity, then walk away.

3. 2.5L Iron Duke (Tech IV I4)

The Iron Duke (or Pontiac 151), though technically a Pontiac design, became a mainstay in Chevrolet vehicles throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. This 2.5L inline-four was built for fuel efficiency, low emissions, and basic transportation, and that’s exactly what it delivered.

Unfortunately, none of these goals align with the kind of robust performance or unique appeal that makes an engine worth rebuilding.

The Iron Duke was constructed with simplicity and durability in mind. It featured a cast-iron block, cast-iron head, and an overhead valve design that made it easy to maintain but also made it heavy and inefficient. It was underpowered from the start, often producing under 100 horsepower.

That number might’ve been acceptable in the early ‘80s, but by modern standards, it’s abysmal. Even extensive rebuilds with new internals, ported heads, and improved intake/exhaust setups rarely push it past 130–140 horsepower, and that’s with a major investment.

The rebuild process itself isn’t particularly difficult, but it is profoundly unrewarding. Because the Iron Duke never had a performance-oriented version, the aftermarket support is nearly nonexistent. There are no stroker kits, no high-performance cylinder heads, no turbo kits designed for it.

Even tuning solutions are limited because the engine’s factory fuel management systems were rudimentary at best. Attempting to modernize or extract power from an Iron Duke is like trying to turn a garden tractor into a race kart — technically possible, but practically absurd.

Even as a budget engine, the Iron Duke fails to justify itself. For a fraction more, you could rebuild a 3.8L Buick V6 or a modern Ecotec and see massive gains in power, drivability, and reliability.

The Iron Duke doesn’t even offer much in terms of nostalgia — it was never featured in any iconic performance car, and even its use in vehicles like the Fiero was quickly overshadowed by V6 upgrades.

In conclusion, the Iron Duke’s only real value lies in extreme originality restorations or as a conversation piece about how low the bar for performance was in the early ‘80s. If you’re looking for a rebuild project that delivers power, satisfaction, and long-term usability, the Iron Duke is the antithesis of everything you should be aiming for.

4. 3.4L V6 (LA1 60° V6)

The 3.4L LA1 V6 was a staple in GM’s front-wheel-drive sedans, minivans, and crossovers during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Found in vehicles like the Chevrolet Impala, Monte Carlo, Venture, and Oldsmobile Alero, this engine was part of the long-running 60-degree V6 family.

Though reliable under ideal conditions, the 3.4L gained notoriety for a laundry list of engineering issues that make it one of the least desirable GM engines to rebuild, even as a stopgap solution.

The most infamous problem with the 3.4L LA1 is its intake manifold gasket design. These gaskets are prone to failure, allowing coolant to leak internally or externally. Left unchecked, this often leads to head gasket failures, overheating, and cracked heads.

Rebuilding one of these engines means not only replacing the obvious wear items but also meticulously addressing weak points in the cooling system, manifold sealing, and even the torque spec of the bolts — all to avoid repeating the same failures shortly after reassembly.

From a performance perspective, the 3.4L is simply underwhelming. With outputs around 180–200 horsepower and limited torque, it never offered exciting performance, even when new. Worse yet, the aftermarket for the 3.4L is almost nonexistent. Unlike the 3800 Series II, which has cult-like support, the 3.4L LA1 has virtually no performance community behind it.

That means few camshaft options, weak tuning support, and almost no bolt-on parts. For the money it takes to rebuild one, you could buy a running LS-series truck engine and be miles ahead in power and future potential.

The rebuilding process itself is surprisingly intensive for an engine that returns so little. Because of its transverse layout and tight engine bays, accessing critical bolts or components during removal and reinstallation can be frustrating.

Additionally, due to its low power and cheap vehicle applications, most 3.4Ls are run into the ground, meaning cores often come with significant wear, making machining or replacing major components mandatory. This drives up cost, which is hard to justify when the end product is still lackluster.

If you’re trying to rebuild a daily driver on a shoestring budget, it’s understandable to be tempted by a 3.4L core. But the truth is, even for economy builds, there are better alternatives — both in the GM family and beyond.

The 3.4L is a classic example of an engine that is more expensive to fix right than to replace entirely with something better. Unless you have a unique emotional attachment to the car or are using it as a temporary bridge, this is one rebuild not worth the time or money.

5. 2.5L Tech IV / Iron Duke II

The 2.5L “Tech IV,” also referred to as the second-generation Iron Duke, was used throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s in GM’s front-wheel-drive vehicles. GM attempted to carry forward the Iron Duke’s basic design into more modern platforms like the Chevrolet Cavalier, Celebrity, and Pontiac 6000.

While slightly more refined than the original Iron Duke, the Tech IV still suffered from the same issues that plagued its predecessor, making it another clear case of an engine that should never be rebuilt unless you’re restoring a car for originality.

One of the biggest flaws of the Tech IV was its complete lack of performance. Even with throttle-body fuel injection and mild head redesigns, it remained a painfully slow engine. It never produced more than 110 horsepower, and its torque curve was as flat and uninspired as the sedans it powered.

No matter how much effort you put into rebuilding it — new rings, high-compression pistons, ported heads — you’ll still end up with an engine that can barely keep up with modern traffic, let alone provide any driving excitement.

Another challenge with rebuilding the Tech IV is parts availability and price justification. While OEM replacement parts exist, performance parts are almost nonexistent. You won’t find aftermarket cams, turbo kits, or high-flow intake systems.

Even when considering basic components like timing gears or lifters, you’re often paying a premium simply because they’re rarely produced today. For the same budget, you could rebuild a 2.2L Ecotec or swap in a 3800 V6, and end up with better performance, reliability, and resale value.

From a mechanical standpoint, the Tech IV is more complicated than it seems. The block casting isn’t particularly robust, and it has trouble handling increased cylinder pressures or RPM. While the Iron Duke was known for its ruggedness, the Tech IV doesn’t share the same reputation for bulletproof reliability.

It tends to develop oil leaks, head gasket failures, and even valvetrain wear issues earlier than you’d expect — all of which erode the value of rebuilding it even further.

Unless you’re preserving a museum-quality example of a base-model 1989 Chevy Celebrity, there’s simply no reason to rebuild the Tech IV. It offers nothing in terms of performance, tuning flexibility, or aftermarket fun.

It’s a relic from an era of cost-cutting and emissions compliance — a time when engines were made to survive just long enough to meet EPA standards, not to be brought back to life and celebrated. Let the Tech IV rest in peace, and choose a powerplant that rewards your hard work instead.

Also Read: 5 Best and 5 Worst Ford Eco-Boost Engines To Know

Engine rebuilding isn’t just a mechanical task — it’s a statement. It says that you, the builder, believe in redemption, in restoration, and in raw, roaring internal combustion. But even with the best intentions, rebuilding the wrong engine can feel like pouring your time and money into a leaking oil pan.

That’s why knowing which Chevrolet engines are worth your effort — and which are better left alone — is one of the most important decisions you can make in your automotive journey.

Throughout Chevrolet’s long and storied history, some engines have risen to the top as legendary icons of durability and performance. Others? Well, they barely deserve a footnote.

The Chevrolet 350 small block, LS1, 454 big block, 283 small block, and 6.0L LQ4/LQ9 are all engines that combine historic value, mechanical simplicity, upgrade potential, and widespread parts availability.

These are platforms that allow you to tailor your rebuild to your exact goals — whether that’s high-revving street performance, brute-force torque, or a period-correct restoration. Rebuilding one of these engines is more than feasible — it’s fulfilling. The aftermarket support, community knowledge, and mechanical reliability of these platforms turn your hours in the garage into a long-term reward.

Contrast that with the 305 and 267 small blocks, the Iron Duke, 3.4L V6, and Tech IV 2.5L. These engines, though part of Chevrolet’s vast lineage, represent the low points of engineering compromises, underwhelming performance, and poor support.

They were born in eras of economic pressure, emission crackdowns, and corporate cost-cutting. Rebuilding one of these engines often results in an expensive, underperforming engine that’s frustrating to tune and ultimately unsatisfying to drive. There’s no joy in rebuilding an engine that can’t be improved beyond mediocrity — and worse, that no one wants even when it’s done.

But here’s the good news: You don’t have to learn these lessons the hard way. By understanding the history, strengths, and limitations of each platform, you can approach your next build with confidence. The difference between a rebuild that becomes a badge of honor and one that becomes a long, slow mistake lies in preparation.

Research. Smart selection. And knowing when to say “no” to that cheap core engine that looks tempting but isn’t worth the hours it will cost you.

What makes an engine worth rebuilding isn’t just power or pedigree — it’s potential. Can it grow with your skills and needs? Will it teach you something about the craft of engine building?

Does it offer a balance between performance, reliability, and affordability? The engines in the “worth rebuilding” category answer those questions with a resounding yes. The ones in the “not worth touching” list, however, often demand more than they give, and for most builders, that’s a deal-breaker.